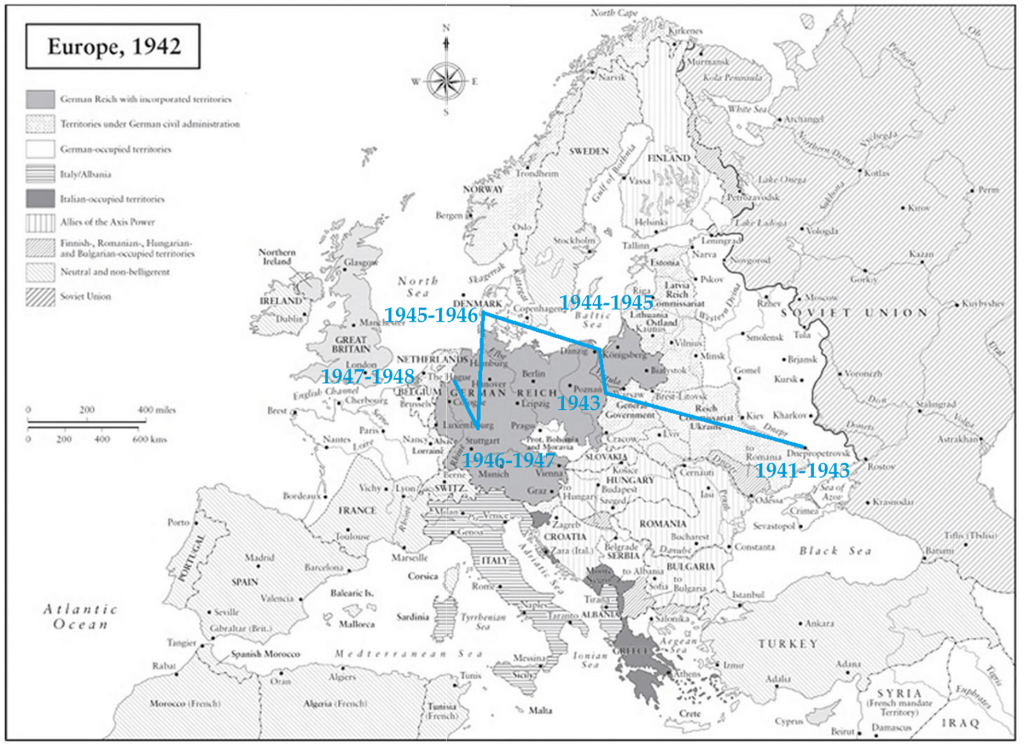

What did it mean to be Mennonite during the Holocaust? The records of a Nazi death squad that killed tens of thousands of Jews in Ukraine during the Second World War offer one perspective. This death squad, Einsatzgruppe C, produced detailed reports for superiors in Berlin on a nearly daily basis during Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. In addition to meticulous counts of Jews, communists, and others murdered under their command, the officers of Einsatzgruppe C devoted substantial attention to pockets of German-speaking communities that they encountered across Ukraine, including large Mennonite settlements. These wartime documents show how the Third Reich’s most infamous killing units treated local Mennonites while perpetrating genocide.

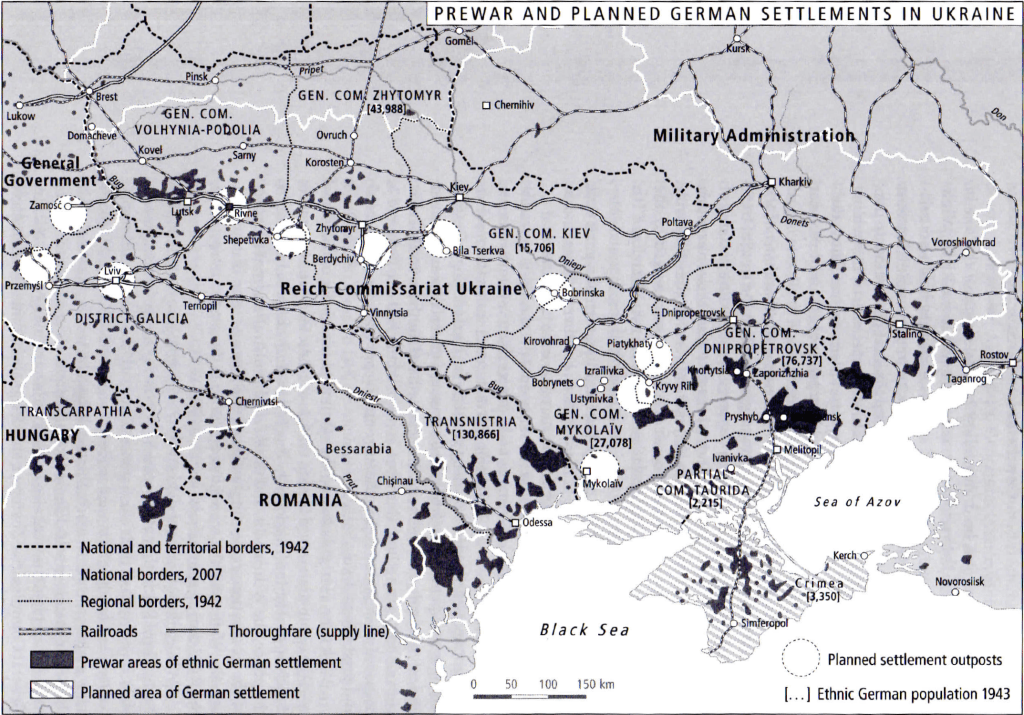

Einsatzgruppe C was one of four major death squads (labeled A, B, C, and D) that the SS created in 1941 to conduct ethnic cleansing and racial warfare in newly conquered regions of the Soviet Union. Each Einsatzgruppe operated in the wake of an army group. They collectively comprised about 3,000 members. These murder units grew more ruthless as they went, at first killing mostly men, but then also slaughtering women and children. Einsatzgruppe C worked in areas destined for civil administration. This territory became the Reich Commissariat Ukraine. It encompassed several Mennonite colonies including the region’s oldest settlement, Chortitza. By contrast, the largest colony, Molotschna, lay to the south in a military district assigned to Einsatzgruppe D.1

Experiences in western and central Ukraine with Lutheran and Catholic German speakers shaped Einsatzgruppe C’s attitudes toward the Mennonites it encountered farther east. Prior to invading the Soviet Union, Nazi officials feared that few “ethnic Germans” would be left alive in the areas they conquered, and that those remaining would be hardened communists. Invaders were instead pleased to discover large groups of anti-Bolshevik German speakers. “The impression that these people make is surprisingly good,” Einsatzgruppe C reported. “There can be no talk of any kind of Bolshevization.”2 The murder team immediately began integrating these ethnic Germans into its operations, distributing Jewish plunder and placing trusted men in positions of local authority.

The death squad’s officers expressed ambivalence toward Christian piety among ethnic Germans it encountered. On one hand, religious belief had helped preserve their morale during decades of communist oppression. But Einsatzgruppe C also felt the Bolshevik ban on churches had yielded a “positive result,” in that the previously strong divisions between Christian denominations had begun to dissolve, giving way to a common attitude of racial unity: “Clergy must be prevented from reestablishing lines of denominational division.”3 This view was almost certainly shaped by Einsatzgruppe C’s in-house racial expert, Hans Beyer. As a prolific academic and editor, Beyer was well versed in the history of Ukraine’s Mennonites, whom he would soon meet in person.4

Hans Beyer and other members of Einsatzgruppe C arrived in areas of Mennonite settlement by September 1941. Their sub-unit, Einsatzkommando 6 (EK 6), established temporary headquarters in the city of Kryvyi Rih. In evaluating ethnic German villages around Kryvyi Rih, EK 6 devoted attention to what it considered a “strange mixed settlement” called Stalindorf. Thousands of Jews lived alongside hundreds of ethnic Germans. The latter group included Mennonites, described as being of “Dutch” origin but nonetheless fully Germanized. The pre-Soviet state had settled these families as model farmers for the Jews. “The Jews conducted a regime of terror and rigorously exploited the German farmers,” EK 6 reported. “The hate against the Jews is accordingly large.”5

To what extent can historians trust the sociological evaluations of a genocidal murder squad like Einsatzgruppe C? The officers of this unit possessed a fanatical hatred of Jews that led them to drastically misunderstand the basic dynamics of communist society. “Our experiences confirm the earlier assumption,” one report asserted, “that the Soviet state is in the purest sense a Jewish state.”6 Members appear to have truly believed that Jews controlled every significant political organization, city administration, and commercial enterprise in Ukraine. To “liquidate” Jewish leaders—and eventually the entirety of the region’s Jews—made strategic and economic sense to the killers of Einsatzgruppe C, who saw murder as a prerequisite to breaking Bolshevik power.

Einsatzgruppe C hoped that local populations, including Mennonites, would share its extremist views. The death squad’s officers were therefore predisposed to overstate anti-Judaism among locals. Yet Nazi expectations also pushed these groups to become more antisemitic than they might otherwise have been. To convince Ukraine’s general populace that mass murder would be carried out mainly against Jews, officers marched victims through villages in broad daylight. They also involved local militias in the killings, distributing complicity. “Executions of Jews were everywhere accepted and viewed positively,” Einsatzgruppe C evaluated. “What is striking is the calm with which the delinquents allow themselves to be shot, both Jews and non-Jews.”7

The death squad took pride in killing a small number of ethnic Germans known to have served as Soviet bureaucrats or police informants. “The population’s trust in [our] activities,” officers reported, “has been further strengthened because in necessary cases, the most serious measures are also taken against ethnic Germans.”8 SS leaders expressed special disgust for ethnic Germans who had helped Bolshevik police arrest, deport, or kill fellow Germans. Einsatzgruppe C showed remarkable leniency, however, to individuals who claimed that their work for Soviet offices had been coerced. Indeed, numerous former Soviet secret police agents of myriad ethnic backgrounds collaborated with Nazi occupiers, offering their service in hopes of surmounting suspect pasts.9

One former Soviet agent who joined Einsatzgruppe C was a Mennonite woman named Amalie Reimer. Originally from the Chortitza settlement, Reimer had slipped behind German lines as an undercover Soviet spy. Instead of completing this task, however, she defected. Asking to speak with the highest German authority, Reimer arrived at the EK 6 headquarters in Kryvyi Rih. She told the death squad that she had been forced into spying against her will. Reimer explained that Soviet police had deported her husband, and they further threatened to imprison her and to harm her five-year-old son. EK 6 extended Reimer the benefit of the doubt. The death squad’s officers treated her tale as reliable evidence of ethnic Germans’ horrific oppression under communism.10

Historian Doris Bergen has argued that the Nazi term “ethnic German” (Volksdeutsche) helped to exacerbate antisemitism among German speakers in Eastern Europe during World War II. People categorized as ethnic Germans could access favorable treatment from Hitler’s forces. Achieving this desirable status often required racial appraisal. Applicants could provide genealogical data or demonstrate their fluency in German folkways. Borderline cases could also prove their political loyalty by participating in Holocaust atrocities.11 Records produced by Einsatzgruppe C suggest that the term “Mennonite” constituted an even more desirable sub-category of belonging than the more general “Volksdeutsche” designation. Hopes for high status gave incentives to collaborate.

The case of Amalie Reimer illustrates how the concept “Mennonite” held coveted value during the Holocaust. Although EK 6 did not yet know it when Reimer presented herself in Kryvyi Rih, she was a persona non grata in her home community of Chortitza. Numerous local Mennonites firmly believed that Reimer had not been forced to act as a Soviet spy. Rather, they saw her as a hardened communist who had personally betrayed many fellow ethnic Germans. One rumor even held that Reimer, having grown unhappy in her marriage, had sold out her own husband to the Soviet secret service. Reimer made sure to steer clear of her hometown, where accusations against her had convinced the Mennonite chief of police to arrest her, should she ever return.12

Reimer may have been rejected by her fellow Mennonites, but she carefully portrayed herself to Nazi authorities as a good and upstanding community member. Nazi officers who interviewed Reimer in Kryvyi Rih clearly accepted her motives.13 An autobiographical account penned later in the war reveals what Reimer probably told her interviewers. “I had a joyful childhood,” she wrote, “and was raised in the Mennonite faith.” Reimer underlined this information. It was the only phrase she underlined in the entire document, including her discussion of atrocities against ethnic Germans, reference to Stalin’s secret police as a “Jewish organization,” or promise to be a “loyal daughter of the German country.”14 For Reimer, being Mennonite already implied the rest.

SS race experts considered members of the denomination to be unusually pure and industrious specimens of Aryanism. Einsatzgruppe C expressed ambivalence toward Mennonite religiosity, but officers were no more disparaging than they had been toward the faith of the Lutherans and Catholics already evaluated to the west: “Despite their religious fundamentalism, their German racial consciousness and faith in the Führer and Reich has been uniformly strongly awakened.”15 Indeed, a comprehensive SS report on German speakers in eastern Ukraine (based on data from Einsatzgruppe C as well as from units to the south) concluded that “the Mennonites make the consistently best physical and spiritual impression of all the ethnic Germans assessed so far.”16

High-ranking Nazi officials accelerated the Holocaust precisely as killing squads arrived in areas of Ukraine with large Mennonite populations. The head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, visited EK 6 in Kryvyi Rih in early October. This trip helped Himmler formulate plans to reshape Ukraine as an Aryan utopia. After Himmler told subordinates to intensify their murder operations, EK 6 shot Jewish women for the first time.17 Himmler also tasked an SS officer who had accompanied him to Ukraine, Karl Götz, with eventually importing hundreds of thousands of German farmers from overseas for settlement in Eastern Europe.18 Götz envisioned a special role for Mennonites in this process, and he reached out to denominational leaders in Germany to coordinate plans.19

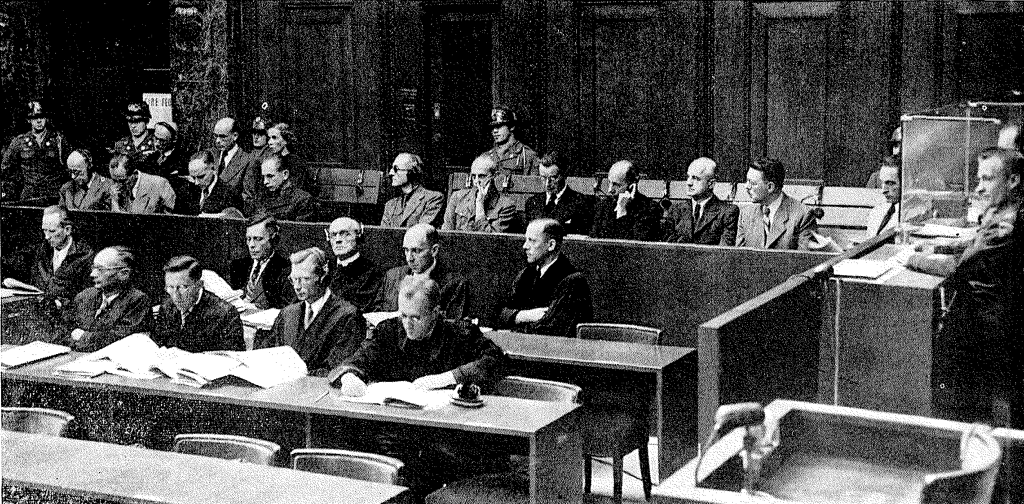

More local Mennonites, besides Amalie Reimer, soon became entangled in the activities of EK 6. Himmler’s visit to Kryvyi Rih had coincided with the Nazi conquest of Zaporizhzhia, a large city near Chortitza. From October 5 to November 19, EK 6 reported murdering 1,000 Jews during operations in the Dnieper Bend, and it initiated plans to kill 1,500 individuals with mental and physical disabilities.20 Some local Mennonites denounced their neighbors as the SS arrived, and others may have directly participated in shootings. At a postwar trial, one former commander of EK 6 reported that a number of ethnic Germans had joined the death squad: “There were students who had experienced how their parents were shot. It actually frightened us, what bloodlust they had.”21 Further reserach is required to understand the full extent of Mennonite participation.

The brutality of the Nazi occupation created violent cycles that drew Mennonites and others into crimes. While in the Zaporizhzhia region, EK 6 complained that its work had been hampered by huge quantities of denunciations. “Nearly all the residents consider it necessary,” officers wrote, “to self-interestedly denounce their relatives, friends, etc., to the German police as having been communists.”22 The complexity of assessing these accusations’ validity in turn created roles for local collaborators to prove their worth. Amalie Reimer—after retrieving her son, whom she had hidden with a Russian family—traveled with EK 6 to the regional capital, Dnepropetrovsk. She worked there for the General Commissar and regularly performed confidential tasks for the SD.23

Regardless of whether other Mennonites continued onward with EK 6, its decisions—along with the wartime empowerment of ethnic Germans—ensured local Mennonites’ further involvement in genocide. EK 6 in fact murdered fewer Jews than some comparable death squads. It did not shoot most of Zaporizhzhia’s Jews, explaining: “due to the considerable shortage of skilled workers, we had to keep Jewish craftsmen alive for the time being.”24 Similarly in Stalindorf, EK 6 left most Jews to work.25 Between October 1941 and May 1942, local Mennonite authorities thus participated in the ghettoization, enslavement, and murder of remaining Jews. Some received plunder from the 2,500 Jews in Stalindorf.26 Others helped organize the shooting of 3,700 Jews in Zaporizhzhia.27

National Socialists’ genocidal plans to infuse the ethnically cleansed regions around Ukraine’s Mennonite colonies with vast new migrations of Aryan settlers never came to fruition. Battle losses on the eastern front forced Hitler’s armies into retreat by 1943. Instead of bringing more colonists to Ukraine, the SS evacuated Ukraine’s Germans to the west. Most found themselves in refugee camps in or near occupied Poland. The Third Reich planned to naturalize nearly all these evacuees as German citizens. In a twist of fate, a prominent Mennonite named Johann Epp—the former chief administrator of the Chortitza colony, who was now helping Nazi officials evaluate evacuees’ suitability for citizenship—found Amalie Reimer and her son in one of the camps.28

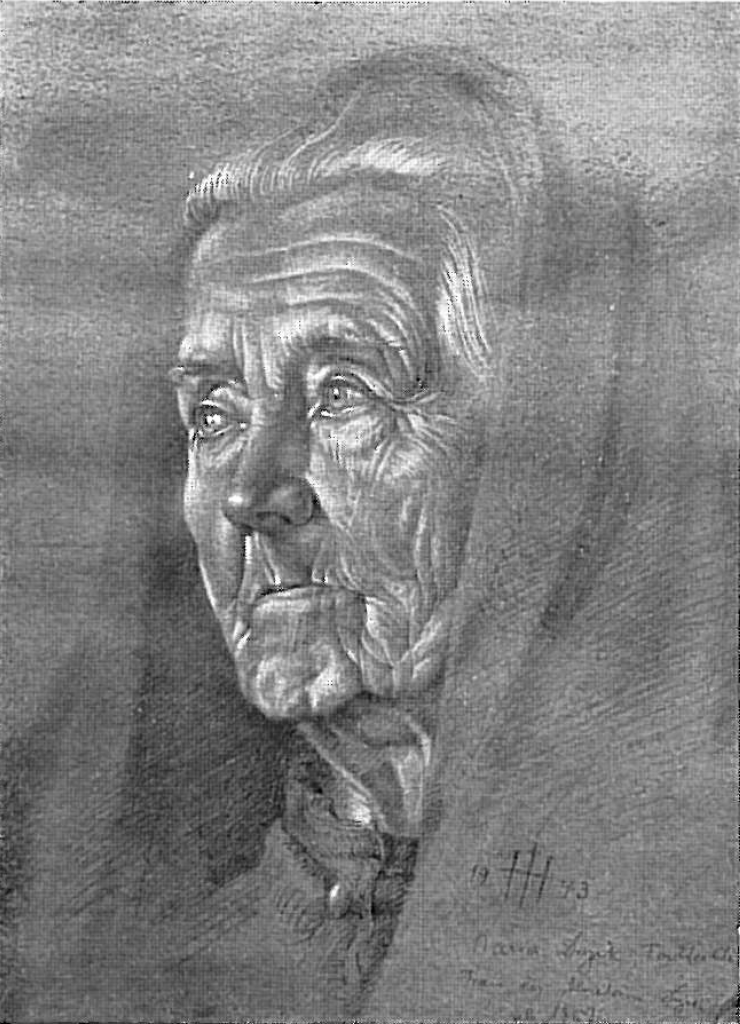

The unexpected meeting in 1944 between Amalie Reimer and the Mennonite Johann Epp offers a final opportunity to analyze the denomination’s relationship to Einsatzgruppe C. Epp believed that Reimer was a former communist agent, and he recommended she be denied citizenship. Reimer appealed to her SS superiors. They affirmed that her work in Ukraine outweighed any “rumors” and suggested that she be employed in a concentration camp.29 Epp, in turn, submitted damning statements by himself and four other Mennonites, who accused Reimer of betraying kith and kin while fraternizing with Jews and socialists.30 In the end, Reimer was denied citizenship.31 In this remarkable exchange, the opinions of Mennonites outweighed the desires of leading SS officers.

To be within the Mennonite fold during the Holocaust was to wield influence. Einsatzgruppe C’s records prove that prominent Nazis believed killing Jews would rectify communist violence against ethnic Germans. Mennonites, moreover, enjoyed a higher reputation than did ethnic Germans generally. They could even defeat SS officers in disputes. After the war, Mennonite evacuees in Western Europe repurposed tales of suffering in the USSR to cast themselves exclusively as victims. Amalie Reimer adopted this position in postwar testimony at Nuremberg.32 Like thousands of others, she and her son migrated to the Americas through help from Mennonite aid societies.33 Knowledge about the denomination’s connections to a major Nazi death squad subsided, until recently, into obscurity.

Ben Goossen is a historian at Harvard University. He is the author of Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, published by Princeton University Press. Thanks to Laureen Harder-Gissing for providing sources for this essay and to Madeline J. Williams for her comments.

1 It would be valuable to systematically trace Einsatzgruppe D’s interactions with Mennonites during its operations in Transnistria, Crimea, southern Ukraine, and the Caucasus, as this essay does for Einsatzgruppe C’s activities in the Reich Commissariat Ukraine. On Einsatzgruppe D and Mennonites, see Mark Jantzen and John Thiesen, eds., European Mennonites and the Holocaust (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), 3-4, 57-62, 210-220.

2 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 81,” September 12, 1941, in Die “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR” 1941: Dokumente der Einsatzgruppen in der Sowjetunion, ed. Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Andrej Angrick, Jürgen Matthäus, and Martin Cüppers (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2011), 454.

3 Ibid.

4 See Hans Beyer, Aufbau und Entwicklung des ostdeutschen Volkstums (Danzig: Paul Rosenberg, 1935), 109-110; Hans Beyer, “Hauptlinien einer Geschichte der ostdeutschen Volksgruppen im 19. Jahrhundert,” Historische Zeitschrift 162, no. 3 (1940): 519. In 1937, Beyer strategized with Mennonite denominational leaders about how to improve their reputation in Nazi Germany. “Aus der Unterredung Beyer-Regehr (Danzig),” October 4, 1937, Vereinigung Collection, folder: Briefw. 1937 Jul-Dez, Mennonitische Forschungsstelle, Bolanden-Weierhof, Germany (hereafter MFS). Beyer’s interlocutor may have been Ernst Regehr, elder of the Rosenort Mennonite congregation, who had joined the Nazi Party on June 1, 1931. According to “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 85,” September 16, 1941, in Die “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR” 1941, ed. Mallmann, Angrick, Matthäus, and Cüppers, 483, Beyer spoke to ethnic Germans in Zhytomyr. He arrived with Einsatzgruppe C in Chortitza by the end of September 1941. Karl Roth, “Heydrichs Professor: Historiographie des ‘Volkstums’ und der Massenvernichtungen,” in Geschichtsschreibung als Legitimationswissenschaft, 1918-1945, ed. Peter Schöttler (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1997), 291-294.

5 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 85,” September 16, 1941, 468-469.

6 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 81,” September 12, 1941, 451.

7 Ibid., 455.

8 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 80,” September 11, 1941, in Die “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR” 1941, ed. Mallmann, Angrick, Matthäus, and Cüppers, 444.

9 Jeffrey Burds, “Turncoats, Traitors, and Provocateurs”: Communist Collaborators, the German Occupation, and Stalin’s NKVD, 1941–1943,” East European Politics & Societies and Cultures 32, no. 3 (2018): 606-638.

10 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 88,” September 19, 1941, in Die “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR” 1941, ed. Mallmann, Angrick, Matthäus, and Cüppers, 497-498.

11 Doris Bergen, “The Nazi Concept of ‘Volksdeutsche’ and the Exacerbation of Anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe, 1939-45,” Journal of Contemporary History 29 (1994): 569-582.

12 David Löwen to Johann Epp, April 24, 1944, Einwandererzentralstelle Collection, A33420-EWZ50-GO62/2902-2954, Mennonite Archives of Ontario, Waterloo, ON, Canada (this file hereafter cited as MAO).

13 Friedrich Werner to Hermann Behrends, February 2, 1944, MAO.

14 “Handschriftliche Aufzeichnungen der volksdeutschen Angestellten (ehem. Lehrerin) Amalie Franziska Reimer, geb. am 3. Jan. 1911 (in Chortitza im Rayon Saporoshe),” ca. February 1944, MAO. It is possible that whoever typed Reimer’s handwritten account may have added the underlining, in which case its meaning would be different. Regardless, Reimer took pains to portray herself in this seven-page document as belonging to Chortitza’s Mennonite community, which she depicted positively in contrast to Judaism, communism, and the Soviet secret police.

15 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 86,” September 17, 1941, 484. Leading Mennonites exhibited antisemitism in correspondence with fellow denominational leaders. The district administrator of Chortitza, for example, praised the Nazi invasion for ending an era in which “Jews and Jew-lovers sat in our villages and played their evil games.” Quoted in Benjamin Unruh to Johann Epp, December 5, 1943, Vereinigung Collection, folder: 1943, MFS.

16 “Das Deutschtum im Raum von Kriwoj Rog, Saporoshje, Dnjepropetrowsk, im Gebiet Melitopol und im Gebiet Mariupol: Vorläufige Feststellungen, insbesondere über die Mennonitensiedlungen,” November 1, 1941, in Deutsche Besatzungsherrschaft in der UdSSR 1941-45: Dokumente der Einsatzgruppen in der Sowjetunion, ed. Jürgen Matthäus, Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Martin Cüppers, and Andrej Angrick (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2013), 221-226, here 223. This report’s information on Mennonites in areas under Einsatzgruppe C’s jurisdiction had been collected from September 19 to 23; information on Mennonites in the area under Einsatzgruppe D’s jurisdiction had been collected from October 17 to 24.

17 Heinrich Himmler, Der Dienstkalender Heinrich Himmlers 1941/42 (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 1999), 224-225.

18 On Götz’s anticipated postwar role in resettling Germans from overseas, see “Ratsherrn Karl Götz, Stuttgart,” September 19, 1941, A3343 SSO, roll 21A (Karl Götz 11.3.03), National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, USA. One version of this plan envisioned bringing 200,000 settlers from overseas. These were to join nearly two million total settlers intended for Eastern Europe, where one major new province called Gotengau would be erected in a region known for its historic Mennonite populations: “the Dnieper Bend, Taurida, and the Crimea.” “Stellungnahme und Gedanken von Dr. Erhard Wetzel zum Generalplan Ost des Reichsführers SS,” April 27, 1942, in Vom Generalplan Ost zum Generalsiedlungsplan, ed. Czeslaw Madajczyk (Munich: Saur, 1994), 51-52. Nazi planers contemplated a special role for South American migrants in their hypothetical Gotengau: “Here we could perhaps trade [with South American countries] to get back the South America Germans, especially the Germans from southern Brazil, [in exchange for Polish settlers whom the Nazis wanted to remove from Europe] and locate them in the new settlement areas, possibly in Taurida and the Crimea as well as the Dnieper Bend.” Ibid., 63.

19 Götz wrote to the Mennonite leader Benjamin Unruh on October 24, 1941 with the goal of facilitating a meeting between Unruh and Himmler. Meir Buchsweiler, Volksdeutsche in der Ukraine am Vorabend und Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs—Ein Fall Doppelter Loyalität? (Gerlingen: Bleicher Verlag, 1984), 321. On Götz and his relationship to Mennonites, see Benjamin W. Goossen, “‘A Small World Power’: How the Third Reich Viewed Mennonites,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 75, no. 2 (2018): 173–206.

20 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 135,” November 19, 1941, in Die “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR” 1941, ed. Mallmann, Angrick, Matthäus, and Cüppers, 818. EK 6’s rate of murder accelerated as compared to the period from September 14 to October 4, during which it reported killing 106 political functionaries, 48 saboteurs and plunderers, and 205 Jews. Mallmann, Angrick, Matthäus, and Cüppers, ed., Die “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR” 1941, 673, 777.

21 Ernst Biberstein’s testimony from June 29, 1947 at the Einsatzgruppen Trial in Nuremberg is quoted in Buchsweiler, Volksdeutsche in der Ukraine, 377. Records of ethnic German evacuees processed by the Einwandererzentralstelle in 1944 offer one avenue for identifying Mennonites previously recruited by the Einsatzgruppen. For instance, the file of one Chortitza colony resident reports that he joined the SiPo and SD on November 11, 1941, while EK 6 was still in the Dnieper Bend; after transfer to a different area in October 1943, he was listed as affiliated with an “Einsatzkommando.” Jakob Ediger, “Einbürgerungsantrag,” April 13, 1944, Einwandererzentralstelle Collection, A3342-EWZ50-B034/1214-232, Mennonite Archives of Ontario, Waterloo, ON, Canada. [Caption edited 7/26/2022]

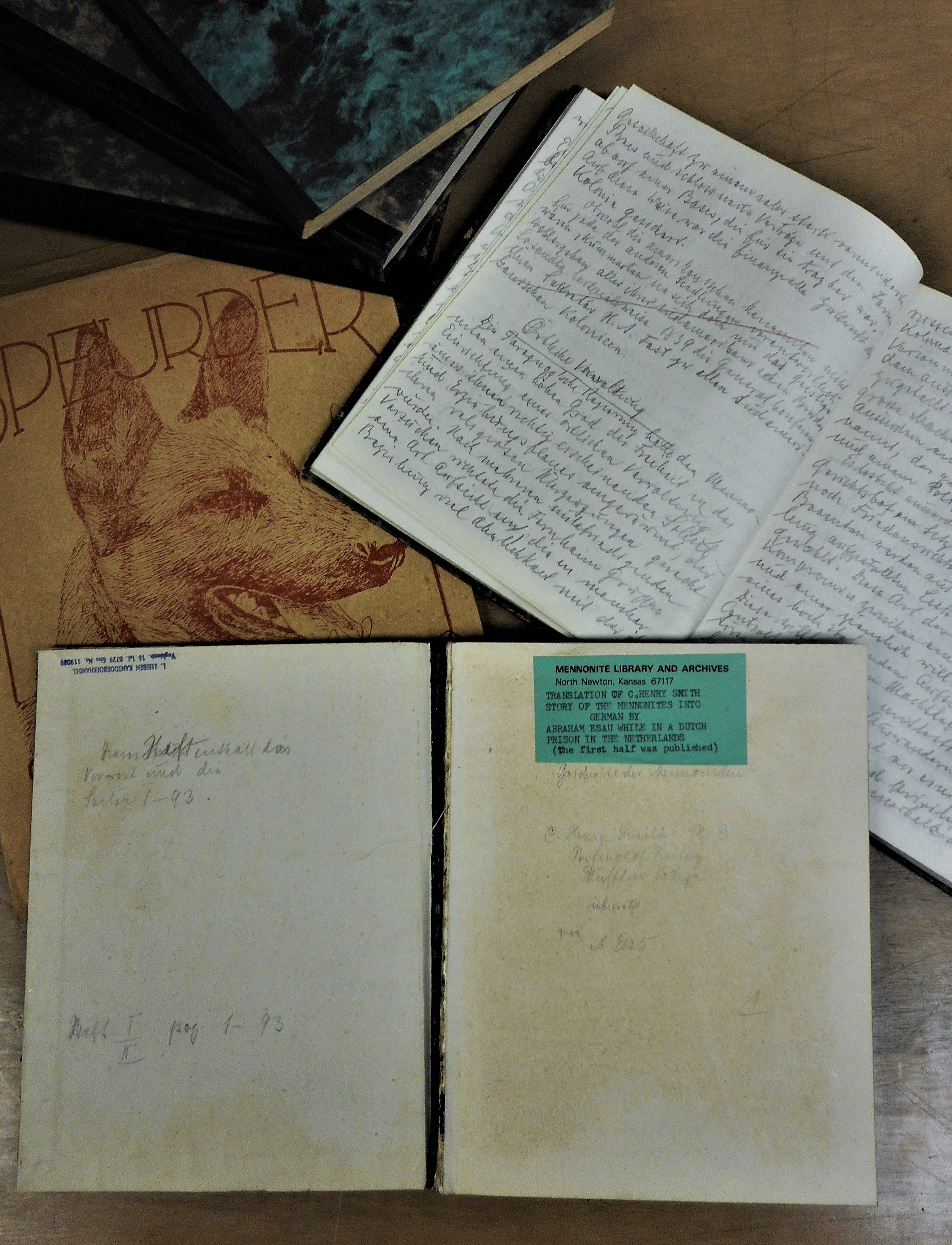

22 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 135,” November 19, 1941, 818. This complaint applied generally to the Dnieper Bend region, where Mennonites were only a minority of the population, but the pattern also held for Mennonites. In one case, a Mennonite in Zaporizhzhia who had reportedly “betrayed several ethnic Germans” to the Soviets died of illness before he could be tried by Nazi authorities. Benjamin Unruh to Vereinigung and Verband, October 18, 1943, Vereinigung Collection, box 3, folder: Briefw. 1943, MFS. In a postwar interview, Heinrich Wiebe (who had served as the mayor of Nazi-occupied Zaporizhzhia) discussed another case: women in Chortitza had denounced a fellow Mennonite named Niebuhr for betraying their husbands to the Soviet secret police. Niebuhr avoided punishment by joining the Gestapo. Wiebe added: “Among our Mennonites, very many unfortunately joined the Gestapo. Many.” Heinrich Wiebe, Interview, ca. 1950s, Cornelius Krahn Interviews, tape 5, side B and tape 6, side A, Mennonite Library and Archives, North Newton, Kansas, USA.

23 “Amalie Reimer worked in various capacities as a trusted agent for the Security Police and SD office that I headed in Dnepropetrovsk.” Hermann Ling to Chef der SiPo and des SD, EWZ, Lager Litzmannstadt, March 24, 1944, MAO. Ling had previously been an officer with Einsatzkommando 5 of Einsatzgruppe C. While in Dnepropetrovsk, Ling oversaw the enslavement of thousands of Ukraine’s remaining Jews. Ray Brandon and Wendy Lower, eds., The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 43, 205. Reimer may have arrived in Dnepropetrovsk prior to the massacre of around 15,000 Jews in that city by mid-October of 1941. 5,000 Jews reportedly remained alive in Dnepropetrovsk as of October 19. Mallmann, Angrick, Matthäus, and Cüppers, ed., Die “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR” 1941, 821.

24 “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 135,” November 19, 1941, 818.

25 “EK 6 decided against shooting these Jews in the overriding interest of continuing the [agricultural] work, being satisfied with liquidating the Jewish leadership.” “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 81,” September 12, 1941, 452.

26 Buchsweiler, Volksdeutsche in der Ukraine, 381, gives the number 2,500 for October 1941. On their ghettoization and murder, see Danielle Rozenberg, Enquête sur la Shoah par balles, vol. 1 (Paris: Hermann, 2016), 65-119. Most of Stalindorf’s able-bodied Jews were sent in April 1942 to work on the Dnepropetrovsk- Zaporizhzhia highway. Martin Dean, Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941-44 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 83. Stalindorf’s remaining Jews were killed in May 1942. Wila Orbach, “The Destruction of the Jews in the Nazi-Occupied Territories of the USSR,” Soviet Jewish Affairs 6, no. 2 (1976): 44. Further research is required regarding Mennonites’ relationship to the killings. Viktor Klets, “Caught between Two Poles: Ukrainian Mennonites and the Trauma of the Second World War,” in Minority Report: Mennonite Identities in Imperial Russia and Soviet Ukraine Reconsidered, 1789-1945, ed. Leonard Friesen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 304. Some empty Jewish homes were given to Mennonites, and Stalindorf was renamed Friesendorf after their “Frisian” heritage. See “Dorfbericht: Friesendorf,” July 7, 1942, R 6/623, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, Germany (hereafter BArch).

27 See Aileen Friesen, “Khortytsya/Zaporizhzhia under Occupation: A Portrait,” in European Mennonites and the Holocaust, ed. Jantzen and Thiesen, 229-249; Gerhard Rempel, “Mennonites and the Holocaust: From Collaboration to Perpetuation,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 84, no. 4 (2010): 530-535.

28 Reimer had been trying to leave the camp and gain new employment. An SS-Brigadeführer had already written on her behalf to a Nazi office in Reichsgau Sudetenland, noting that she “had made notable contributions to the German cause.” Rudolf Creutz, “Rußlanddeutsche Umsiedler-Lehrerin Amalie Reimer,” March 15, 1944, MAO. For Johann Epp’s initial evaluation of Reimer’s citizenship application, see Amalie Reimer, “Einbürgerungsantrag,” March 19, 1944, MAO. Epp’s title at this time was “Volkstumssachverständiger bei der Einwandererzentralstelle-Kommission XXVIII.” Epp had already rejected other evacuees’ applications on similar grounds. Benjamin Unruh to Vereinigung, January 7, 1944, Nachlaß Benjamin Unruh, box 4, folder 21, MFS.

29 Ling to Lager Litzmannstadt, March 24, 1944. Ling had found a position for Reimer at the Potulice concentration camp, where she would have worked with kidnapped children of anti-German partisans from the Soviet Union. Regarding Johann Epp’s charges against Reimer, Ling added: “One must know the context of the ethnic Germans from Zaporizhzhia to know that there, Russian rule caused much internal malice.”

30 Accusations by Luise Schmidt, Anna Cornies, and Johann Rempel are contained in K. Löwen to Johann Epp, March 31, 1944, MAO; Johann Epp, “Meine Stellungnahme zum Lebenslauf der Amalie Reimer,” April 24, 1944, MAO; David Löwen to Johann Epp, April 24, 1944. See also Rudolf Rempel, “Vernehmungsniederschrift,” April 24, 1944, MAO.

31 Regierungsrat to Niedenführ, April 4, 1945, MAO. This process took over a year to resolve. Already by mid-1944, however, the accusations against Reimer resulted in the revocation of her employment offer at the Potulice concentration camp. Authorities who weighed the evidence for and against Reimer considered the Mennonites who denounced her to be “Russia German evacuees, who not only have known her for years, but who also must be seen as leading people within Germandom.” Schapmeier to Ehrlich, June 10, 1944, MAO.

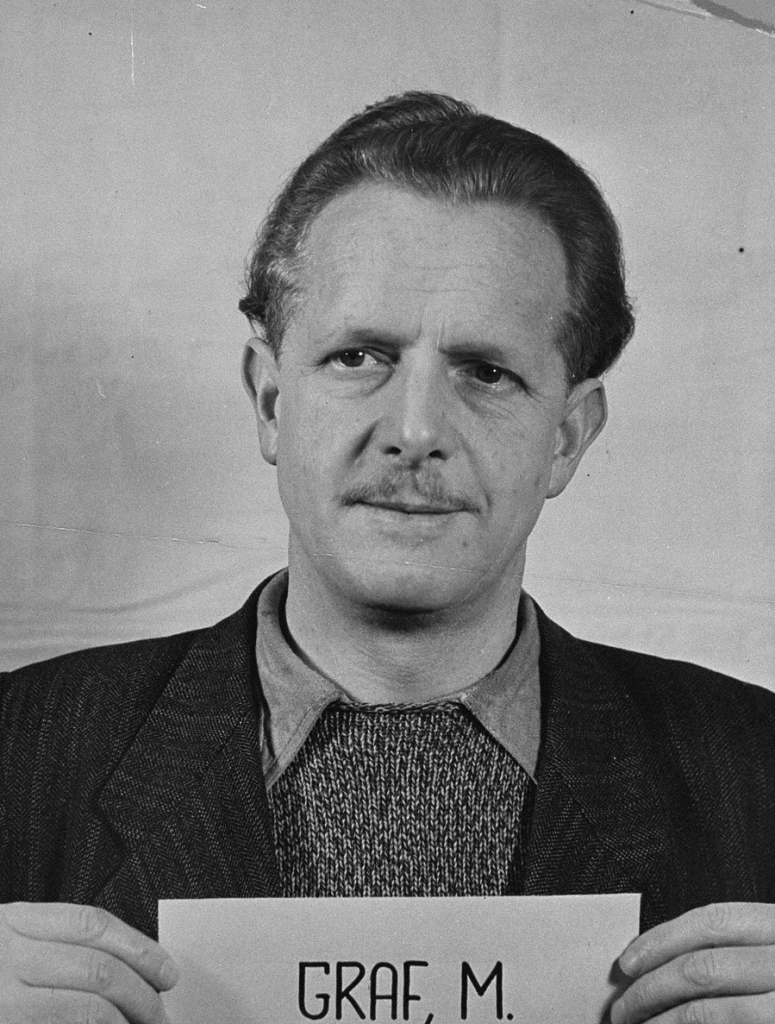

32 Instead of working at the Potulice concentration camp, Reimer had received employment in a factory through the help of a former EK 6 officer, Matthias Graf, and she later testified (under her middle name, Franziska) on his behalf at Nuremberg. See Erika Weidemann, “Identity and Survival: The Post-World War II Immigration of Chortitza Mennonites,” in European Mennonites and the Holocaust, ed. Jantzen and Thiesen, 269-289. The racial expert Hans Beyer also remained in contact with Mennonites after his service with Einsatzgruppe C. See Hans Beyer to Christian Neff, May 31, 1944, Nachlaß Christian Neff, folder: Briefwechsel 1944, MFS; Benjamin Unruh to Vereinigung, November 21, 1944, Nachlaß Benjamin Unruh, box 4, folder 21, MFS.

33 Reimer and her son left for Canada on November 4, 1948, sponsored by A. Reimer of Lockwood, Saskatchewan. Hermann Schirmacher, Hans Peter Wiebe, and Thomas Schirmacher, eds., “MCC Auswanderungslisten nach 1945: The Mennonite Central Committee Post-World War II Refugee List, 1945-1952,” 2020, Mennonite Genealogical Resources, online.