“Not all the Jews were bad,” a widely respected Mennonite born in interwar Ukraine told me recently, “even though they started the [Bolshevik] Revolution. My father had good Jewish friends.” This statement is classically anti-Semitic. It falsely conflates communism with Judaism, while using the excuse of having a few Jewish friends to mask an implied belief that Jews in general were bad. At least as importantly, my conversation partner’s words reveal how people who do not consider themselves racist or anti-Semitic can still propagate harmful myths.

New scholarship and ongoing public discussion about the historic entanglement of tens of thousands of Mennonites on three continents with Nazism and the Holocaust during the 1930s and 1940s has yielded productive conversation regarding how present-day Anabaptists can and should respond to this history, as well as calls for further discussion. At the same time, some church-affiliated periodicals have printed articles, letters, and reviews that propagate troubling interpretations of Mennonite-Nazi connections, including anti-Semitic tropes.

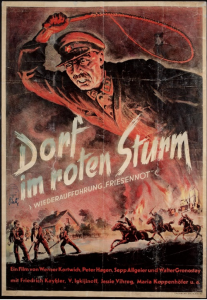

Imagery of the “Great Trek” during WWII has dominated Mennonite depictions of the era, bolstering a narrative of suffering, mostly female refugees. In fact, the word “trek” was widely and triumphally used in the Third Reich to describe German-speakers relocating from Eastern Europe to Germany. This particular movement of Mennonites and others out of Ukraine in 1943 and 1944 was overseen by the SS. Participants were not primarily considered to be refugees but rather Aryan “re-settlers,” traveling to a fatherland newly cleansed of Jews. Credit: Mennonite Archives of Ontario, attributed to Hermann Rossner.

Such reactionary responses are not exceptional, either in Holocaust historiography or in the current context of Israeli human rights abuses against Palestinians. In February, Poland passed legislation criminalizing mention of some Poles’ involvement in genocide, while part of the international backlash to Israeli violence has been couched in anti-Semitic terms. When certain Mennonites voice anti-Semitic sentiments, this often reflects—as is the case of other groups—both an attempt to protect their own and also a real, dangerous current of anti-Jewish prejudice.

The following five myths date to the Third Reich or its immediate aftermath. They remain in circulation, deployed today to excuse Mennonite involvement in Nazism or to foreclose public discussion. Examples given below all appeared in Mennonite periodicals within the past two years. Since my intention is to stimulate thoughtful reflection, not to shame individuals, I have chosen not to cite most quotations. However, all are easily accessible online and in print.

Myth #1: Mennonites suffered under Bolshevism, justifying Nazi collaboration.

This is the most typical excuse for Mennonite involvement for Nazism. The trope holds that life in the Soviet Union was so brutal, Mennonites had no choice but to embrace Hitler’s crusade. In fact, most Mennonites involved with the Third Reich had never lived in the USSR. The subset who did—approximately 35,000 individuals in Ukraine—came under Nazi occupation in 1941. Like millions of other Soviet citizens, most of these Mennonites welcomed Hitler’s armies as “liberators” from hardship and repression. Yet unlike the majority of their neighbors, Mennonites were generally considered Aryan, a status that provided additional incentives to support Nazism.

This trope is often accompanied by assertions that Mennonite suffering under communism has not been properly recognized. But in reality, Mennonite authors have been publicizing Soviet atrocities without abate since the Bolshevik Revolution. Scholarly literature and memoirs on Mennonite victimhood greatly outnumber texts that explore collaboration or perpetration. Nearly all of the latter have appeared only recently. The imbalance is so stark that Mennonite historians can claim to have created an entire subgenre on the “Soviet Inferno,” a term in academic use since the 1990s and whose deployment continues to refer almost exclusively to Mennonites.

Myth #2: The Allied powers committed atrocities, too – why should we single out Nazism?

“The Nazis were bad, but the Bolsheviks were worse,” a Mennonite born in the USSR told me in March. “You mean from a Mennonite perspective,” I said. My conversation partner shrugged. “Of course.” When white Mennonites think about what life might have been like for them if they had lived in Hitler’s Germany, they invariably assume that they would have been Mennonite—and by extension Aryan. From such a viewpoint, each of the Allied powers, not just the Soviet Union, would have posed a greater threat to life and livelihood than Nazism. In other words, assuming one would have been Aryan creates a false equivalency that downplays genocide.

Studying the Holocaust from a Mennonite-centric perspective runs the added risk of repeating debunked Nazi propaganda, such as the myth that Bolshevism was Jewish. Some invocations of a “Soviet Inferno” falsely imply systematic persecution or even a “final solution” of Mennonites (by Jews) in the USSR. Nazi perpetrators commonly used such reversals to portray themselves as the true victims. Last year, one historian explained Mennonite participation in Nazi death squads, stating: “men and women of Jewish background worked as [Soviet] administrators, agents, and interrogators.” He had previously directed me to a webpage entitled “Jewish Mass Murderers.”

Myth #3: Mennonites were mostly women and children, so they either had no choice or could not have been involved.

Women and children are often invoked to claim Mennonite innocence in Nazi war making. One writer recently claimed, for example: “in the 1930s most Mennonite men [in the USSR] had been exiled, imprisoned or executed, leaving families to be led by mothers and grandmothers,” who were not “collaborators, anti-Semites or Aryan.” Mennonites in Nazi-occupied Ukraine were indeed disproportionately women and children. But there were also plenty of men—many of whom served in administrative positions, as translators, policemen, or soldiers. Gender disparity at the end of the war in part reflected the death or capture of Mennonite men in German uniform.

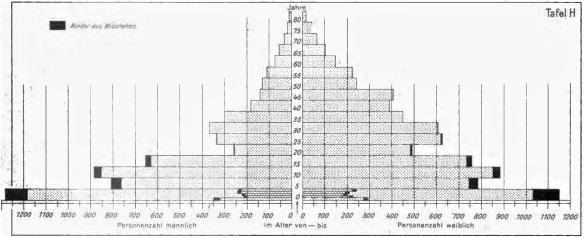

A table compiled by Nazi occupiers showing the age and gender (men on the left, women on the right) of the 13,000 “ethnic Germans” in Ukraine’s Chortitza colony, ca. 1942. Forty-three percent of “ethnic German” families in Chortitza had no male head of household—but fifty-seven percent did. Source: Karl Stumpp, Bericht über das Gebiet Chortitza im Generalbezirk Dnjepropetrowsk (Berlin: Publikationsstelle Ost, 1943), Tafel H.

This myth further assumes that women or children could not have contributed to Nazism or the Holocaust. However, many Mennonite women served as translators or in bureaucratic capacities, sometimes enriching themselves with the spoils of genocide. More often, women supplied moral support to male relatives and contributed to the war effort through their labor. Meanwhile, some underage boys took up arms. And most Mennonite children in the Third Reich absorbed Nazi ideals at school and through organized youth activities. They helped boost morale by singing, marching, and telling stories. Some racist proclivities learned in the 1930s and 1940s persist today.

Myth #4: Mennonites knew nothing about Holocaust-related atrocities.

This is simply untrue, as numerous archival documents testify. Nonetheless, the way this myth is told is itself revealing. Consider one statement: “Although Mennonites under German occupation witnessed how their Jewish neighbours packed up and fled, they did not know about the outcome of this fleeing until much later.” Another, strikingly similar account holds that Mennonites “saw their Jewish neighbours pack up and flee eastward across the Dnepr; how many survived and how many were executed on the eastern side they did not know until later.” These authors care more about locating killing elsewhere than considering why Mennonites stayed as Jews fled.

A caption in one Mennonite history book for this scene from the Molotschna colony in Ukraine, 1942, reads: “This photo shows the uneasy meeting of two branches of the German and Low German cultures: the militarism of Prussia as well as of the Third Reich, and its opposite—the nonresistance of the Mennonite religious culture. The worldwide German culture is much richer given the existence of a community that did not soil itself with the militarist Nazi madness.” In fact, the men pictured here belonged to Waffen-SS cavalry units composed mostly of Mennonites. The photo was taken at a rally where Mennonite women and children performed for the visiting head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler. Source: Adina Reger and Delbert Plett, eds., Diese Steine: Die Russlandmennoniten (Steinbach, MB: Crossway Publications, 2001), 332.

To suggest that murder did not occur around some Mennonite settlements or that Mennonites in these areas had no knowledge of genocide is a form of Holocaust denial. Such myths repudiate known facts. Yet claims persist that Mennonites “had not heard of Aryanism and other racial theories until well after the conclusion of the war.” The author of this line, in subsequent postal correspondence, described glowingly her own wartime work as the secretary for a top German officer in Nazi-occupied Dnipropetrovsk, her receipt of German citizenship, and the voluntary induction of Mennonite men into the military; “I am a beneficiary of the German occupation!”

Myth #5: Mennonites suffered under Nazism.

Among the most disingenuous myths about Mennonite life under Nazism, this trope holds that the general suffering of Mennonites in the USSR continued under German rule. Nazi occupation was indeed catastrophic for a minority of Mennonites who were committed communists, as well as for disabled individuals and those of Jewish heritage. Some in Nazi-occupied France and the Netherlands joined the resistance or hid Jews. Yet claims of Mennonite suffering normally refer to those who in 1943 and 1944 participated in the “Great Trek” from Ukraine to Poland to escape the Red Army—an endeavor supervised by the SS and praised by Mennonite leaders at the time.

Indeed, closer inspection reveals that allegations of Mennonite hardship are often complaints that Nazism did not live up to its potential. If only the Eastern Front had held; if only religious reform had been more thorough; if only welfare programs were more generous—then Mennonite life would have been easier. Even the Holocaust and other persecutions are said to have “occasioned much disappointment among Mennonites.” This may be true. But note how the author chooses to emphasize the “disappointment” of Aryans, not the actual enslavement and slaughter of Jews. Despite the fading of his own initial “euphoria” for Germany, he could remain “deeply grateful.”

* * *

Mennonite authors and editors should think carefully before writing or printing pieces about the Third Reich. This is an important topic and requires our attention. But we must approach it in ways that do not recapitulate racism. Even those of us with good intentions need to be wary. In April, the cover story of a major denominational magazine laudably covered Mennonites and the Holocaust; yet in her introduction, the editor blithely compared Mennonites murdering Jews to Jews murdering Jesus—arguably the single most injurious trope of Christian anti-Semitism. Proofreaders apparently saw no problem with invoking “the crowd that yelled ‘Crucify him!’”

A few rules of thumb might be helpful. If you are discussing Nazism or the Holocaust, consider how someone from a different background might react—particularly if you are defending actions by your own group. Second, be aware of contextual differences: refocusing from the Holocaust to Soviet atrocities erases the specificity of Jewish genocide. Finally, when evaluating suffering, do not discriminate. While Mennonites have faced many difficulties, they never suffered alone. Nor were they always victims. Anabaptists, of all people, must surely grasp that violence can permeate even the most peaceable of cultures, a process we should understand but never justify.

Ben Goossen is a historian at Harvard University. He is the author of Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, published in 2017 by Princeton University Press.

Bookending Doris Bergen’s lecture “Neighbors, Killers, Enablers, Witnesses: The Many Roles of Mennonites in the Holocaust” was the call for more scholarship. Her talk, the keynote of the Mennonites and the Holocaust Conference and convocation for Bethel College, focused on the challenges of doing Holocaust scholarship. Bergen—who is Chancellor Rose and Ray Wolfe Professor of Holocaust Studies at the University of Toronto—explored five specific challenges, increasing in difficulty, with the note that “like those nesting dolls”, each opens new issues even as the resolve others.

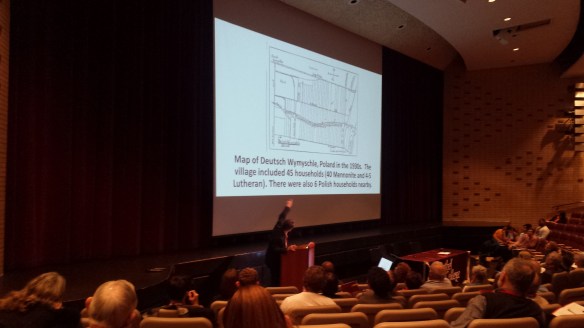

Bookending Doris Bergen’s lecture “Neighbors, Killers, Enablers, Witnesses: The Many Roles of Mennonites in the Holocaust” was the call for more scholarship. Her talk, the keynote of the Mennonites and the Holocaust Conference and convocation for Bethel College, focused on the challenges of doing Holocaust scholarship. Bergen—who is Chancellor Rose and Ray Wolfe Professor of Holocaust Studies at the University of Toronto—explored five specific challenges, increasing in difficulty, with the note that “like those nesting dolls”, each opens new issues even as the resolve others. The fourth challenge was the questions “how do we avoid writing scholarship that is moralistic or judgemental?” Bergen’s response was to start by noting that studying genocide does not imply that she would personally have done better had she lived in a genocidal context, but “scholarship is about analyzing and understanding–how could people like us behave certain ways?” She also warned against the tendency to use avoiding judgement as a way to avoid discussion. This also gets caught up with the maintenance of Mennonite mythology. One solution given was to use the tools of genocide scholarship, which use comparison. “Mennonites were not unique, though distinctive, many of the issues we explore have been and are being confronted by many other people,” said Bergen, “These can be humbling and extremely liberating.”

The fourth challenge was the questions “how do we avoid writing scholarship that is moralistic or judgemental?” Bergen’s response was to start by noting that studying genocide does not imply that she would personally have done better had she lived in a genocidal context, but “scholarship is about analyzing and understanding–how could people like us behave certain ways?” She also warned against the tendency to use avoiding judgement as a way to avoid discussion. This also gets caught up with the maintenance of Mennonite mythology. One solution given was to use the tools of genocide scholarship, which use comparison. “Mennonites were not unique, though distinctive, many of the issues we explore have been and are being confronted by many other people,” said Bergen, “These can be humbling and extremely liberating.”