By Samuel Boucher

When leaving the gates of our tightly knit Mennonite community, and we´re often asked, ¨What’s your nationality?¨ in a language, we may or may not understand well, the answer becomes messy very quickly, ‘I’m Mexican, holding a Canadian citizen, I don’t really speak Spanish or English, I speak Plautdietsch which is a non-written language, and the High German written language I was supposed to learn I didn’t really learn.1

On a cold February morning during the Canadian winter, the bedroom window was completely frosted. I shuffled out of my make-shift bed in the home office of my friend, David2—the principal of an elementary school in a small town in Ontario. I had been touring western Ontario giving a series of lectures to ‘Mennonite’ schools in small Canadian towns. Listowel—the town my friend worked in—had a sizable amount of Old Colony Mennonites, so David had invited me to give a lecture on Mennonite history. Many of these students are recent migrants from Mexico (while still holding Canadian passports). It was a surreal experience to see Mennonite boys and girls in winter coats and fleecy ear-flap hats dropped off by horse-and-buggy to rush into the heated school and pick up their school-issued Ipads and laptops to play academic programs and to write essays. This made me wonder how much Old Colony Mennonites and Old Order Amish are willing to accept these new digital technologies—specifically social media. In the following paper, I will explain the origins of the Mennonites, their conception of migration, their use of social media, and how virtual space may become the new horizon for migration to preserve their cultural identity.

Originating in the Radical Reformation, the Mennonites are an ethno-religious community dispersed in small colonies throughout the Americas. These followers of Menno Simmons have tended to split into small, decentralized churches, beginning with the Swiss Mennonites and the Dutch Mennonites. These two groups followed two different historical trajectories that led their descendants to end up in the Americas. As part of the Radical Reformation, the Mennonites were constantly on the edge of persecution under the pronouncements of the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 (Cuius regio, eius religio/Whose realm, his religion). The Dutch Mennonites fled repeated rounds of persecutions, first to East Prussia, then to New Russia, and finally to Canada. From Canada, the more conservative members and churches left in the 1920s for Latin America in order to maintain their Low German language schools and colony system; they are now known as the Old Colony Mennonites. The Swiss Mennonites fled Switzerland for the New World arriving in the Thirteen Colonies and slowly spreading westward into the Midwest and Canada. These are the familiar Old Order Amish well-known for their Pennsylvania Dutch language and anti-modern outlook.

Several characteristics bind the Mennonites together despite their diffusion. Theologically—like other Anabapists—they reject infantile baptism and believe that church membership should be a conscious decision. Additionally, they uphold absolute pacifism and believe they must remain separated from the ‘World’ following their conceptualization of Two Kingdoms theology.3 For this reason, they tend towards anti-materialism and non-political engagement. Culturally, these insular communities speak their own language (Low German or Pennsylvania Dutch), have their own strictly enforced set of rules (called the Ordnung), and maintain their own customs and beliefs—probably the most well-known one being that they avoid or eschew much of modern technology. Despite these similarities, some differences are rather pronounced between the Old Order Amish and Old Colony Mennonites.

While the Amish have spatially remained in North America and slowly creeped outward from their communities with nearby land purchases, the Low German Mennonites have a history of migration which has become a key aspect of their mythos. Because of their constant movement—The Netherlands-East Prussia-New Russia-Canada-Latin America—the Mennonites never truly settled any geographic parameter long enough to develop a mythic attachment to it. Therefore, they do not hold ties to a nation-state for the ‘Kingdom of Heaven is their fatherland.’

Even beyond not having an attachment to a specific location, Mennonites have an internal need to migrate to replicate their colony system. It is via migration itself that Old Colony Mennonites maintain their community. The Mennonites enter each country with the promise to aid in the development of colonial projects and “accepting citizenship while simultaneously rejecting nationality through the building of a community that spans across state borders.”4 Ironically, it is the anti-modernist sects of the Mennonites who have tended to migrate most frequently transnationally and developed new regions. In the words of historian Royden Loewen, Mennonites “court modern economic forces in order to sustain an antimodern culture.”

Typically, the Mennonites migrate primarily as a means to escape persecution and assimilation. Yet, in many ways, Mennonite colonies also exist as sacred spaces to be differentiated with the outside world as they seek to separate themselves from the evil of the ‘world.’ They construct sacred spaces here on Earth in the form of their colonies, which are conceptually attempts at neo-kingdoms of Heaven. But where can Mennonites now migrate when every territory has now come under the control of the nation-state paradigm? For anthropologist Bottos, the answer is through this transnational network. Bottos explains, “cross-border strategies to flout their incorporation into the nation seems to be the Mennonite answer to the globalization of the nation-state.”5 Yet, another possibility exists. More and more Old Colony Mennonites (as well as Old Order Amish) are using social media as means to maintain this network. The internet has created a means to distort spatial reality by shrinking the distance between these dispersed colonies. It is quite possible that Mennonites will now turn to virtual space as the new frontier of migration.

Several studies have examined the social media and internet use of the Amish and Mennonites. Anthropologist Rivka Neriya-Ben Shahar conducted a comparative survey of the Old Order Amish and Orthodox Jews. Rivka specifically studied whether the Amish women themselves viewed social media and the internet as a net positive or negative. Rivka surveyed forty women of the Old Order Amish community living in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.6 None of the Amish women interviewed had smartphones and only eight percent had ever browsed the Internet.7 While a small number, this may be surprising for the average reader who conceives of the Amish as embodied visions of a distilled past. Despite this minority, most Amish women cast an evil eye toward the internet. Rivka categorized the responses to social media and internet use by the Amish women into:

(1) destruction and ravage—danger, dangerous, catastrophe, spoils the spiritual world, a weapon, harmful; (2) degrading—garbage and filth, bad, shocking, filthy, horrible; (3) temptation—seductive, slippery slope; (4) access—uncensored information, worldly; (5) religious exclusion—impure, evil things forbidden by the church; (6) spiritual effects—destroys souls, influences thoughts; and (7) a waste of time—takes time away from family time.8

In this way, Rivka found that the Old Order Amish women maintained a primarily negative view of social media. But while the mothers are rejecting social media, some of the youths are embracing it.

‘No other site . . . has taken off as massively as Facebook amongst the Amish teens. Everyone is on Facebook.”9 This was told to investigative journalist Justine Sharrock, writing for the popular online blog Buzzfeed in 2013, by twenty-two-year-old who had recently left the Amish. Anthropologist Charles Janzti has recently studied this phenomenon in his article, “Amish Youth and Social Media: A Phase or a Fatal Error.” He has found that many Facebook posts by Amish teens show context of parties and drinking alcohol. One such photo of ‘Amish beer pong’ received twenty likes and three shares.10 Still, the degree to which Amish youth have accepted social media is difficult to estimate. A separate estimate suggests that the earlier quote is widely exaggerated with only one to two percent of Amish youth using Facebook.11 Other specialists on Amish society have suggested that these teens were most likely still in their Rumspringa12 years and moreover, that “many of the youth on Facebook are on the margins, not mainstream Amish youth.”13 But it is very possible that social media is set to take off with the Amish in similar ways that have happened with their religious cousins, the Old Colony Mennonites.

It is estimated that about eighty-five percent of Old Colony Mennonite students in Canada have cell phones while most still do not have televisions nor access to internet in their homes.14 In the 2014 article, “Living on the Edge: Old Colony Mennonites and Digital Technology Usage,” scholar Kira Turner has found that “OCM accept digital technologies more readily than other traditional Mennonites; notably they use cell phones, communicate through social media such as Facebook, and text their families in Mexico.”15 This is especially important when one considers the Mennonites in their transnational context. The Old Colony Mennonites are connected via digital space to their relations in colonies in Latin America while residing in North America. In this way, ironically, certain Mennonites have utilized social media in order to maintain their colony structure and anti-modernist outlook.

Mennonites have used social media for a variety of reasons—including business, networking, and cultural promotion. Mennonite businesses make use of social media for purposes of marketing. A good example is juwie16, an apple juice company hailing from Mexico with the tagline—El Gran Sabor Menonita—the great Mennonite flavor (see the picture below). The Mennonites in Chihuahua are well-known for their apple orchards—controversially, at times, because of the overuse of limited water resources by the Mennonites to irrigate their thirsty orchards. Logically, these Mennonites have then processed their apples into apple juice for added value.

These Mexican Mennonites are much more modern and are more willing to make technological and cultural concessions than the typical horse-and-buggy sects. Importantly, on their website, juwie notes how Cuauhtemoc is considered of the city of the three cultures: Mestizo, Raramuri and Mennonite.

Other more anti-modern groups also make use of the internet and social media for business. Several Amish and Mennonite businesses have combined to publish their businesses on JustPlainBusiness.17 These Amish and Mennonites are joined together as ‘plain’ to distinguish from other Mennonite groups. Plain designates that sect is anti-modern and enforces strict rules for clothing and behavior. One such business is Helmuth’s Country Store which sells Mennonite-built furniture and other home goods (see the photo below).

It is not solely Mennonites in North America using social media for business. I have found several Instagram accounts tied to the Mennonite colonies in Argentina. Of particular note is the coloniasmenonitas account,19 which appears to be a business account for a Mennonite business specializing in the manufacturing of silos (an interesting niche20 that the Mennonites have developed in the Pampas). Despite the commercial nature of their account, the business also posts general photos of the colonists on their farms, churches, and in everyday life (see the photos below).

The Mennonites in Argentina are Old Colony conservative and horse-and-buggy sects. This is evidenced by the primary photos found with the #menonitasargentina. This compares interestingly with the hashtag #menonitasbrasil where the Mennonites exist mostly as a religious category and have culturally assimilated into the mainstream Brazilian society (see the photo below).

Colonias Menonitas are also on Facebook as a business account:

As the posts are primarily in Spanish, it seems that the Facebook business account is mostly marketing to the wheat farmers (needing silos to store grain) in the pampas of Argentina.

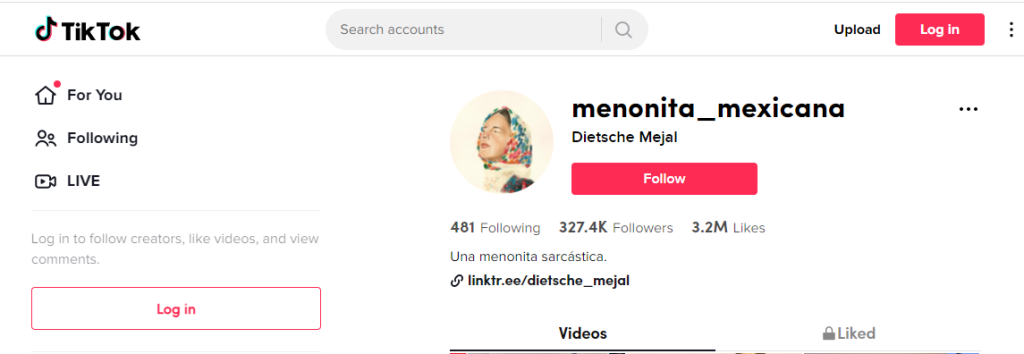

No Mennonites have used social media in order to become an ‘influencer’ with one notable exception: Dietsche mejal, German Girl, (see the photo below) who has accounts on almost all major platforms. Her followers are in the hundreds of thousands across her platforms, and she maintains millions of likes and views. Dietsche mejal—schooled in Canada and living in Mexico—provides content in three languages: English, Low German, and Spanish. She creates content both for Mennonites (with inside jokes and cultural references) as well as non-Mennonites (explanations of Mennonite culture and history).

Dietsche mejal is not the only account to promote Mennonite culture. Comparable to The Onion or The Babylon Bee, The Daily Bonnet21 is a satirical news site written by Andrew Unger based in Steinbach, Manitoba (a historically Mennonite city) catered to a Mennonite audience. Unger also operates a local news site with his wife Erin called Mennotoba which plays off the history of the pioneering Mennonite settlements in Manitoba. These two publications re-enforce Mennonite identity with readership residing across various nation-states including but not limited to Mexico, Canada, United States, and Bolivia.

While business and cultural promotion are interesting uses, the main application of social media by Low German Mennonites is to maintain familial connections across various states and nations. Despite being a transnational group with far-flung colonies across the Americas, Mennonites are a close-knit community. As most transnational groups, families end up being split up on two sides of the globe. In The Madonna of 115th Street, Orsi notes the stress and hardship of this separation for Italian families in the early twentieth century when he writes,

Some immigrants, to be sure, pined for the old country and longed to be back in familiar surroundings. This desire was particularly acute in times of crisis or loss. It could be strong enough to kill: Edward Corsi’s mother died after a long depression brought on by the dislocations of immigration. This powerful nostalgia was alive among the first generation, and those who felt it most acutely served as revealing mirrors to those who were trying to still this longing.22

In the 1920s, many of the Mennonites returned to Canada due to this same feeling of longing for family. Today, WhatsApp and Facebook are the primary platforms for older conservative Mennonites in order to maintain these contacts.

Of these two, perhaps the most important platform for the Mennonite transnational network is WhatsApp. Both Low German and Pennsylvania Dutch are primarily spoken languages. Thus, Mennonites’ preference for WhatsApp is due to its VoiceNote function. With the VoiceNote function, Mennonites are able to leave vocal recordings to their contacts rather than writing and reading text messages. As Mennonites exist in various nations, they may write and read English, Spanish, German, or Portuguese to varying degrees. Low German is the connecting language for this community. As a spoken language, only a social media platform with internet usage that provided a function that enabled a primarily oral message system would the Mennonites have been able to properly use in their transnational context. This was noted by Anna Wall, a healthcare interpreter, in her blogs on the Mexican Mennonite community in Canada. Wall writes,

As the years passed and the rest of the world evolved, more and more of us became illiterate. Living in a Spanish-speaking country, speaking Plautdiesch at home, also known as Low German and reading and speaking only High German at school and church, writing letters as a means to stay connected became more and more challenging, to say the least.23

Wall goes on to state that the app is especially useful for transnational groups that crisscross borders since it does not change plans or phones, a transnational media for a transnational group.

Amongst themselves, the use of new technologies is a constant debate in horse-and-buggy communities such as the Old Order Amish and Old Colony Mennonites. Typically, the Mennonites have addressed new technologies in three ways: assimilation, limited adoption, or separation. Additionally, some Mennonites have circumvented this problem of modern technology has been to outsource the function to a third party: they hire someone. This is especially common for horse-and-buggy communities to hire taxis for travel into town when they are forbidden to own cars. Other debates have split churches. Rivka notes that “The emergence of landline phones set off a big debate among the Amish and led to a schism in 1910, with one-fifth of the congregation leaving the Amish church. The Amish see the telephone as ‘an umbilical cord tied to a dangerous worldly influence.’”24 In today’s context, the debate consists of prohibition of cellphones and social media use being a constant feature in their preachers’ sermons.25 Still, several Amish interviewees seem unworried about this development. Janzti writes, “An Amish father, who grew up in the late 1970s and early 1980s, suggested that there is little difference between what can be seen on Facebook today and what exists in photo albums tucked away from his era of Rumspringa.”26 Each Mennonite community has contended with these new technologies in different ways. Turner elaborates, “The David Martin Mennonites keep their computers in the barn or shop for business purposes but not in the house, while Markham-Waterloo Mennonites have gone to great expense to create their own server so they can manage their members’ Internet access.”27 Therefore, the response to technology exists on a wide spectrum for the Mennonites. More progressive Amish and Mennonite communities have phones and use social media while the stricter communities do not have access to smartphones, the internet, or social media.28

It is important to understand that Mennonites do not simply reject all technologies out of hand. New technology is simply not accepted without stiff deliberation. The main focus is on the net benefit or negative that the adoption of the technology will have on the community. Thus, Mennonites consider the usefulness of the technology while technology for entertainment’s sake is rejected out of hand in the more restrictive communities. There is also a distinction between spaces. Business spaces are considered separate from the home space and are given more allowances for more technological use due to this consideration. Business is inherently connected to the outside world due to the needs of supply and customership.

Limited adoption has often been taken by these communities where they have implemented technologies with modifications that allow a certain degree of social control on their usage. Plainizing digital technologies into non-internet access contraptions.29 This ‘plainization’ has even become a verifiable niche industry within the Amish community. One entrepreneur, Allen Hoover, retrofits tools to run on alternative power with the tagline—made specifically for the plain people by the plain people. He has also created what he calls Classic Word Processors, essentially computers without internet access.30 The Hutterites—a related Anabaptist group—have even created their own internal network service within their colonies to maintain control over what comes in through their servers.31

Several scholars have commented on the possible consequences of social media on these isolated communities. Rivka views the use of social media as contrary to the core values of community-oriented groups such as the Amish. She writes, “The individualism, autonomy, personal empowerment, and networking that characterize new media pose a challenge to the core values of religious communities: traditionalism, cultural preservation, collective identity, hierarchy, patriarchy, authority, self-discipline, and censorship.32” For Rivka, the internet and social media poses a danger of breaking the self-imposed boundary of sacred space (home) and ‘the world.’33 Rivka believes that social media use will break down community boundaries following studies by scholar Meyrowitz (1985) who observed that electronic media erodes the boundary between the private and public spheres.34 Importantly, Rivka primarily interviewed Amish women due to the concept of ‘gatekeeper’ for traditional values. According to Rivka, women exist in Amish Mennonite communities as the main gatekeepers for religio-cultural preservation.35

While Janzti ponders that “perhaps Amish young people have always engaged in this level of self-reflection and discussions regarding their perceived experience and the perception that those outside of the Amish have”, but he ultimately seems unconvinced. He notes that “the difference today, however, is that the internet both provides a window on the Amish world and gives the Amish a platform to reflect on themselves and their culture in a public fashion.” Ultimately, Janzti agrees with Rivka that Facebook (and other forms of social media) are contrary to Amish-Mennonite beliefs. These platforms are designed to be self-oriented with “the whole premise of the ‘selfie’ is the individual.”36 Furthermore, these platforms have a fundamental difference between earlier technologies such as television: they allow for the interactive engagement of the user with the outside world.37 Janzti argues that the internet’s true danger is not in exposure to sex and violence or in change of Amish behavior during their youth but in changing the core values of the Amish community.38

Anthropologist Kira Turner disagrees with Rivka’s and Janzti’s conception of the Mennonites. Turner explains that “While digital technologies may create tensions within the community, they also act to blur lines between geographical boundaries, extend social networks, and allow Old Colony Mennonites to create their own vision of the society in which they wish to live.”39 Adoption of new technologies are becoming increasingly necessary in order to navigate and function in the modern world. This includes but not limited to: schoolwork, filling out tax forms, accessing government documents such as immigration requests, banking, applying for employment, and making purchases.40 Furthermore, Turner notes that “digital technology usage within the Old Colony (community) expands and contracts the walls surrounding isolation and separation from mainstream society. Although it allows ideas to flow between groups, it also allows for the shrinking of space locally and globally. It may inevitably lead some to move away from the church, but it also may lead some to strengthen their ties.”41 Evidently, Turner assumes a moderate course for digital technology in Old Order Amish and Old Colony Mennonite communities through deliberate adoption.

To this point, it is interesting to note that the aforementioned Amish youth on Facebook do not seem to be interacting with youth outside of their Amish circles.42 Chris Weber who works with Amish teens in Indiana notes that ‘they use Facebook to do what they would do anyway—connect with one another—and they would not spend their time playing video games on their phones or Facebook.”43 In Pennsylvania, one Amish group have even created a Facebook page solely due to the promotion of benefit volleyball tournaments—a common sport amongst Amish youth.44 The Amish youth have primarily used social media in similar ways that they have used previous technologies.

Social media can be used as a means to maintain Amish-Mennonite separation with the world. In Diaspora in the Countryside, historian Royden Loewen examines how global economic forces uprooted rural folk and displaced them from their family farms. Diaspora uses the comparative history of two Mennonite communities (one in the United States and one in Canada) to explain the ways in which historical and cultural differences between these two settings influenced the Mennonites response to the Great Disjuncture. Mennonites in Hanover had more critical mass to sustain their cultural cohesiveness and lived in a more openly multiculturally accepting Canadian society which allowed for the maintenance of their culture. On the other hand, Mennonites in Meade had more social pressures to assimilate into the general American consensus. The author writes, “Clearly what sociologists of the 1950s claimed to be seeing, an assimilation into mainstream America, was occurring. Mennonites were dressing, speaking, and thinking like their American neighbors.”45 In this way, it is possible that the Mennonites could use social media such as WhatsApp as a means to sustain their critical mass globally and prevent assimilation.

Much work has been done considering the ideas of space and identity. In her book, Performing Piety, cultural anthropologist Elaine Peña writes how:

De los Angeles also spoke of the need to keep and teach “nuestra cultura, nuestra lenguaje” (our culture, our language) to our children . . . Her statements made layers of time and history, tradition and migration, spirituality and affiliation explicit. Michel de Certeau’s claim that “space is a practiced place” provides an optic through which to examine the idea that the specters of past performances . . . Space, as de Certeau suggests, is always in the process of transformation.46

Pena is attempting to understand the production of sacred space. Following ethnographer Pena, I am attempting to consider questions of space and sanctity. Much like Catholics in central Mexico and the Chicago area created Guadalupan shrines as a means to produce spaces of sanctity in a processual manner, Mennonites also produce sacred spaces in the form of their closed colonies. Rather than a single building or shrine, it is the colony territory and the colony network itself that is the sacred space which is created via the process of migration and construction. The act of separation from the proverbial ‘World’ and the Old Colony Mennonite and Old Order Amish attempts at living a simple and peaceful lifestyle produces this sacred space. In this way, I follow Pena’s advice to view “the migration networks and the approaches to local integration as a process— as layers of culture, history, and traditions imbued in specific locations at specific times.”47 Mennonites connect their transnational network via Mennonite mythology to “reinforce the idea of connectivity among sacred spaces in disparate locations based on comparable embodied practices.” I also follow Orsi who explains that the sacredness of a space can be separated from its location. For Orsi, meaning and sanctity is derived from the ‘lived religion’ embodied in the practice and imagination of certain spaces. Thus, spaces become sacred due to the actions and beliefs of the actors using these spaces rather than in the spaces themselves. The behavior of the Digital Mennonites themselves will convert these online platforms into sacred spaces.

From the Reformation to the present, the Mennonites have consistently attempted to develop their own sacred spaces in their colony network. Fleeing persecution and modernity, the Old Colony Mennonites constantly migrate between nation-states while the Old Order Amish settled apart from society within North America. With the complete coverage of territory on the globe within the nation-state paradigm and the increasing interconnectedness of society, the Mennonites need to assimilate, adapt, or use virtual space as a new frontier of digital migration. As previously shown, with Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, these Digital Mennonites have used and are continuing to use social media as a means of preserving their cultural cohesion by transferring their closed colonies which exist as sacred spaces (their neo-Kingdoms of Heaven) into virtual sacred spaces in online isolated communities.

Samuel Boucher is a historian of the Low German Mennonite colonies in Latin America. His main research focuses on the transnational network of the Mennonites and the main drives for Mennonite economic success.

Bibliography

Cañás-Bottos, Lorenzo. 2008. “Old Colony Mennonites in Argentina and Bolivia: Nation Making, Religious Conflict and Imagination of the Future.” Brill.

Janzti, Charles. Jan 2017. “Amish Youth and Social Media: A Phase or a Fatal Error.” The Mennonite Quarterly Review 91 71 – 92.

Kraybill, Donald. 1998. “Plain Reservations: Amish and Mennonite Views of Media and Computers.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 13(2) 99-110.

Loewen, Royden. 2006. Diaspora in the Countryside: Two Mennonite Communities and Mid-Twentieth Century Rural Disjuncture. Toronto: University of Illinois Press and University of Toronto Press.

Orsi, Robert Anthony. 2010. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880 1950 Third Edition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Peña, Elaine A. 2011. Performing Piety Making Space Sacred with the Virgin of Guadalupe. Los Angeles and London: University of California Press Berkeley.

Rohrer, Eunice. 2004. The Old Order Mennonites and Mass Media: Electronic Media and Socialization. Doctoral dissertation. Morgantown: West Virginia University.

Shahar, Rivka Neriya-Ben. 2020. “Mobile internet is worse than the internet; it can destroy our community”: Old Order Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women’s responses to cellphone and smartphone use.” The Information Society, 36:1 1-18.

Shahar, Rivka Neriya-Ben. 2016. “Negotiating agency: Amish and ultra-Orthodox women’s responses to the Internet.” Sapir Academic College, Israel new media & society 2017, Vol. 19(1) 81–95.

Sharrock, Justine. 2 July 2013. “The Surprising, Ingenious Amish Gadget Culture” BuzzFeed News. http://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/justinesharrock/the-surprising-ingenious-amish-gadget-culture.

Turner, Kira. 2014. “Living on the Edge: Old Colony Mennonites and Digital Technology Usage.” Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 2(2) 165-185.

Wall, Anna. 2020. “WhatsApp With the Mennonites?” Woolwich Community Health Care. Nov 10. https://wchcvirtualhealth.wixsite.com/mysite/post/whatsapp-with-the-mennonites.

[1] (Wall 2020)

[2] I had met David in my Low German course in Alymer in Southern Ontario.

[3] Each Protestant sect conceptualizes the Two Kingdoms Theology differently. For the Anabaptists, the two kingdoms are the kingdom of Earth ruled by the devil and the kingdom of Heaven ruled by God.

[4] (Bottos 2008), 2.

[5] Ibid., 71.

[6] (Shahar 2016), 84.

[7] (Shahar 2020), 8.

[8] (Shahar 2016), 86.

[9] (Janzti 2017 ), 80.

[10] Ibid., 86.

[11] Ibid., 72.

[12] Rumspringa means ‘jumping around’ and the Old Colony Mennonites have a similar conception. A similar American idea is ‘sowing your wild oats.’ Essentially, these Amish youths are not yet baptized church members and have lower behavioral expectations.

[13] (Janzti Jan 2017 ), 72.

[14] (Turner 2014), 171.

[15] Ibid., 170.

[17] https://justplainbusiness.com/

[18] https://justplainbusiness.com/helmuths-country-store/

[19] https://coloniasmenonitas.com/

[20] https://siloscoloniamenonita.com.ar/

[22] (Orsi 2010), 20.

[23] (Wall 2020)

[24] (Shahar 2020), 5.

[25] Ibid., 5.

[26] (Janzti 2017 ), 87.

[27] (Turner 2014), 170.

[28] (Janzti Jan 2017 ), 81.

[29] (Shahar 2020), 5.

[30] (Sharrock, 2013)

[31] Discussion with John Sheridan

[32] (Shahar 2016), 82.

[33] Ibid., 85.

[34] (Shahar 2020), 2.

[35] (Shahar 2016), 87.

[36] (Janzti 2017 ), 87.

[37] Ibid., 89.

[38] Ibid., 91.

[39] (Turner 2014), 165.

[40] Ibid., 172.

[41] Ibid., 181.

[42] (Janzti 2017 ), 72.

[43] Ibid., 80.

[44] (Janzti 2017 ), 85.

[45] (Loewen 2006), 101.

[46] (Peña 2011), 43.

[47] Ibid., 10.