Janneken Smucker

When I began researching the relationship of Amish quilts to the art market about ten years ago, I wanted to find the missing link that proved that abstract minimalist artists—like Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Ellsworth Kelly, and others—painting in bold, graphic blocks of color were inspired by Amish quilts. Surely, some of these artists must have noticed Center Diamond and Bars quilts hanging on the clothes lines in Lancaster County while they tooled about the countryside, right? I had heard a rumor that Frank Stella owned and displayed Navajo blankets, so it didn’t seem like such a stretch. And buried in a exhibition catalog I found a reference to Andy Warhol owning a Lancaster County Amish quilt, but his signature pop art shared more in common with the repeat block patterned quilts of the dominant culture, rather than the graphic minimalism of Amish quiltmakers.1 Maybe, just maybe, there was some hidden connection.

An art historian friend offered to get a message from me to Mark Rothko’s children. I asked if Rothko was familiar with Amish quilts, or if the family ever slept under quilts. His heirs’ answer was an adamant “no,” that this signature color field painter was not at all familiar with the craft. Barnett Newman’s widow fielded a similar question from a folk art curator comparing her late-husband’s work to an Amish bars quilt, stating that his intention was to explore the “subtle relationships between stripes and ground,” whereas a quiltmaker was “carrying out a simple pattern.”2

“No. 61 (Rust and Blue)”, by Mark Rothko 1953. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

Perhaps it would not be in a prominent living artist’s best interest to acknowledge being inspired by the artistic work of untrained female artists from a relatively closed religious group. The hierarchies between art and craft, between male-trained fine artists and female needleworkers were rigidly defined in the 1960s and ’70s. A Philadelphia Inquirer review of one of the very first exhibits focused narrowly on Amish quilts noted, “It would probably be difficult to secure loans of paintings from abstract artists if the intention were to show them alongside quilts… hard-edge abstract painters…probably would feel chagrined, I should think, to have their efforts compared… with applied arts – albeit excellent, quintessentially American folk arts such as Amish quilts.”3 But these boundaries began to blur as interest in women’s traditional artforms gained prominence, thanks to feminism, the approaching Bicentennial, the counterculture’s interest in applied arts and crafts, and an otherwise expanding art canon.

While Newman and Rothko may not have acknowledged drawing any inspiration from Amish quilts—and indeed I can find no evidence that they did—another artist who painted in a similar vein did. Warren Rohrer, with deep roots in a Mennonite farm family from Smoketown in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, had grown up sleeping under quilts made by his mother and grandmother. Yet despite living in proximity to the Amish in Lancaster County, he never saw one of their quilts until visiting Abstract Design in American Quilts, a 1971 exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art. He described the Amish Bars quilt he saw there as “simple in design, like ‘modern art,’ and brooding in color, like Rothko.”4

Following this introduction to Amish quilts, Rohrer explicitly drew on the minimalism and graphic simplicity inherent in the bedcovers in his paintings. Rohrer’s mid-1970s paintings reflect both his newfound interest in Amish quilts (his paintings Fields: Amish 1, Amish 4, and Amish 5 share a strong resemblance with Lancaster Amish quilts) and a return to his agrarian roots as his minimalist painting recalled the farm fields of his youth.5 This conscious turning to his own Anabaptist, rural history prompted the Inquirer art critic to observe that unlike most abstract painters whose work had been compared to quilts, Warren Rohrer would not mind this association.

Warren Rohrer, Settlement Magenta, 1980. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with funds contributed by Henry Strater and Marion Boulton Stroud, 1982

And he and his wife Jane Rohrer also began, in his words, “to search for the ‘perfect Amish quilt,’” buying some with the assistance of Philadelphia antiques dealer Amy Finkle.6 And they found quilts, that seem to my eyes, indeed close to perfect, including this one they later gifted to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Center Square Quilt, Artist/maker unknown, American, Amish, Made in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, c. 1900. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Warren Rohrer, 1982

Penn State’s Palmer Museum of Art is slated to exhibit Rohrer’s paintings along with his wife Jane Turner Rohrer’s poetry in a 2020 show titled From Mennonite Fields: Tradition and Modernism in the Painting and Poetry of Warren and Jane Rohrer, exploring the work of these two artists of Mennonite upbringing. Curated by poet and Penn State professor of English, Julia Spicher Kasdorf; director of the graduate program in Visual Studies at Penn State, Christopher Reed; and Palmer curator Joyce Robinson, the exhibit will also feature Amish quilts from the Rohrer’s collection along with Pennsylvania Dutch painted furniture. The exhibit is funded by a Penn State University Strategic Plan Seed Grant.

- Sandra Brant and Elissa Cullman, Andy Warhol’s “Folk and Funk” : September 20, 1977-November 19, 1977 (New York: Museum of American Folk Art, 1977). ↩

- Quoted in Jean Lipman, Provocative Parallels : Naïve Early Americans, International Sophisticates, 1st ed. (New York: Dutton, 1975), 144. ↩

- Victoria Donohue, “Amish Quilts and Abstract Art Blended at ICA,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 8, 1976. ↩

- Warren Rohrer, “My Experience with Quilts (A Bias),” in Pennsylvania Quilts: One Hundred Years, 1830-1930 (Philadelphia: Moore College of Art, 1978). ↩

- David Carrier, Warren Rohrer [Published in Conjunction with the Exhibition “Warren Rohrer: The Language of Mark Making” Held at Allentown Art Museum of the Lehigh Valley, October 23, 2016 – January 22, 2017], (Philadelphia, Pa: Locks Art Publ., 2016), 72–77. ↩

- Rohrer, “My Experience”; Amy Finkel, interview by Janneken Smucker, Philadelphia, PA, May 15, 2008, Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries, https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/catalog/xt71zc7rqw4b. ↩

Portrait of Jan Luiken File created by Phillip Medhurst – Photo by Harry Kossuth, FAL,

Portrait of Jan Luiken File created by Phillip Medhurst – Photo by Harry Kossuth, FAL,

Title page

Title page The new king of Algeria

The new king of Algeria A battle at sea

A battle at sea Baptisms

Baptisms Skiing and sledding

Skiing and sledding The bed

The bed The dishes

The dishes The painter

The painter The fisher

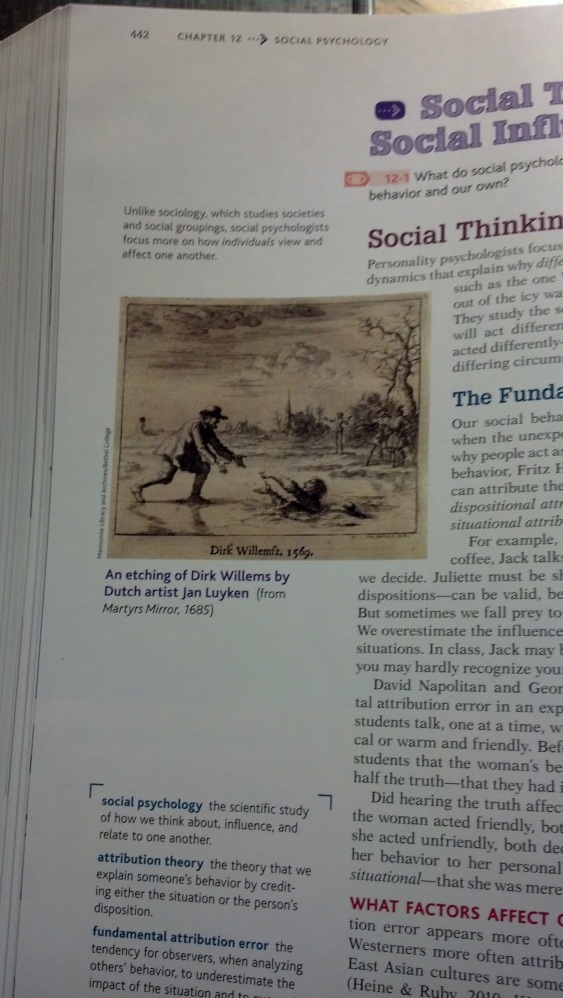

The fisher Artists are in the habit of crossing lines. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp caused an uproar by submitting to an exhibition a mass-produced urinal that he had signed, titled,

Artists are in the habit of crossing lines. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp caused an uproar by submitting to an exhibition a mass-produced urinal that he had signed, titled, Other artists purposefully cross borders of material. Historically, the highly regarded “fine arts” materials of painting and sculpture have far outweighed the importance of craft traditions such as needlework. However, one important legacy of the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s has been the revaluation of media long denigrated as “women’s work.” Karen Reimer employs methods of embroidery and appliqué not only to bring feminized craft traditions into a high art context but also as a means by which to question the value of certain kinds of labor and notions of originality. Reimer intentionally copies her texts from other contexts as a way to destabilize definitions of creativity and innovation. As she writes, “Generally speaking, in the art world copies are of less value than originals. However, when I copy by embroidering, the value of the copy is increased because of the added elements of labor, handicraft, and singularity–traditional sources of value. The copy is now an ‘original’ as well as a copy.”

Other artists purposefully cross borders of material. Historically, the highly regarded “fine arts” materials of painting and sculpture have far outweighed the importance of craft traditions such as needlework. However, one important legacy of the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s has been the revaluation of media long denigrated as “women’s work.” Karen Reimer employs methods of embroidery and appliqué not only to bring feminized craft traditions into a high art context but also as a means by which to question the value of certain kinds of labor and notions of originality. Reimer intentionally copies her texts from other contexts as a way to destabilize definitions of creativity and innovation. As she writes, “Generally speaking, in the art world copies are of less value than originals. However, when I copy by embroidering, the value of the copy is increased because of the added elements of labor, handicraft, and singularity–traditional sources of value. The copy is now an ‘original’ as well as a copy.” Some artists cross lines as a political gesture, seeing their methods as a way to issue public statements, either subtle or explicit. In

Some artists cross lines as a political gesture, seeing their methods as a way to issue public statements, either subtle or explicit. In