This month, October 2019, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, a national demonstration in which millions of Americans protested the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. The Moratorium Day demonstrations—along with the Moratorium March on Washington which occurred that November—marked the first time the anti-war cause manifested itself as a mass movement. An immoral war, an unpopular government, rising public concern about peace and social justice, and a fervent culture of activism all came together to create a strong sociopolitical environment. Within this context in the late 1960s, American Mennonites found themselves in a new and uncomfortable position. For the first time, they were the minority among conscientious objectors and those opposed to war. Popular public objections directed toward the U.S. government ranged specifically to their involvement in Vietnam and more generally to their use of the draft and taxes. In all of these conversations, Mennonite voices were now joined by those of worldly citizens. With the growing unpopularity of the Vietnam War, Mennonites found themselves in the unusual position of being able to openly express their pacifist beliefs without the fear of public criticism, quite a contrast to what they had experienced during previous times of war.

In this new situation, and especially by 1969, Mennonites’ views on conscientious objection, the Vietnam War, and war in general had become muddled. Individually, some Mennonites were engaged in anti-war efforts on religious grounds, while others were more politically or morally motivated. Still others openly supported the government’s efforts in Vietnam. Additionally, any vocal position was criticized by those Mennonites who still upheld traditional nonresistance and two-kingdom theology; those who were in the world but not of it. Even these Mennonites, however, were not immune to the influences of American society. They, too, were becoming divided on the issue of the war, although they did not discuss or act upon these emerging thoughts.

On October 15, 1969, the events of Vietnam Moratorium Day brought the shifting and contested positions of Mennonites in American society into sharp relief. The Bethel College Peace Club’s Moratorium Day demonstration raised serious theological, moral, and social questions among Mennonites about active peacemaking and witnessing to the state. In this sense, this demonstration and the events surrounding it become a microcosm of the debates and transformations which occurred at the denominational level during this period. In remembering the Bethel College Moratorium Day events, one Mennonite remarked, “when there is not a conflict like this here, people tend to settle down and forget about their major beliefs because they’re not pushed on them. But when they’re pushed on them, we have to do some of our best thinking.”1 Fifty years later, as we remember the Bethel Peace Club’s Moratorium Day demonstration, two subjects come to mind: first, the significant impact that these events had on Mennonite faith and identity; and second, the compelling idea that in moments of conflicts of faith, we as Mennonites have to do some of our best thinking.

On October 15, 1969, the large campus bell at Bethel College began to toll. Students of the Peace Club rang the bell every four seconds for four days straight, one toll for each of the forty thousand Americans who had lost their lives in the Vietnam War. This peaceful and powerful act of remembrance had a profound effect at Bethel, with the continuous tolling heard on every corner of the campus and throughout North Newton, acting as a constant reminder of the suffering in Vietnam. Bethel professor J. Harold Moyer remembered the Moratorium Day activities as “one of the most effective things we’ve done.”2

When the bell fell silent four days later on October 18, Bethel College students, faculty, and community members, along with members of other college campuses, marched twenty miles to Wichita’s 81 Drive-In Theater, further exemplifying a resilient commitment to peace. The march ended at the theater with a memorial service led by Bible and religion professor Alvin Beachy. Bethel’s Moratorium Day peace activities captured national attention, grabbing a front page of The New York Times and several spots on national television news broadcasts. Additionally, the national Vietnam Moratorium Committee also found out about the Peace Club’s planned demonstrations and reached out to them in the weeks leading up to October 15 to affirm and encourage the students’ efforts. “Everyone else in the office thought I was out of my mind,” wrote one committee executive, “as I ran around in ecstatic glee talking about the Mennonites and their bell.”3

For many Bethel students, faculty, and administrators, as well as Newton community members, the 1969 Moratorium Day activities brought back memories of the Peace Club’s anti-war protest which occurred three years earlier, in 1966. In November of that year, the Peace Club marched through campus to the North Newton Post Office to deliver letters to their congressional representatives protesting the United States’ involvement in Vietnam. In the weeks leading up to this event, the Peace Club was met with opposition from other Bethel students, administrators (especially from Bethel President Vernon Neufeld,) the Mennonite press, the local American Legion, and other members of the larger Newton community. Threats of violence ensued, the most striking of which was a peace marcher hanged from the Bethel Administration Building in effigy, causing the Peace Club to redirect their march. The 1966 demonstration, which occurred peacefully on November 11, generated considerable conversation among Mennonites. They became divided in their thoughts about the event itself, the theological and moral motivations, and the usefulness of public peace witness.4

Although the Moratorium Day events of 1969 were met with wider support from the community and the nation, the reception on campus was similar to that experienced three years earlier. Professor Alvin Beachy described the relationship between students and administration as a “clash of will.”5 The faculty was deliberate in not holding an official stance on the 1969 peace activities, though many were personally concerned with the war and participated in the student-led activities to show multi-generational support. The administration took a cautious stance, attempting to carefully balance the public image of Bethel College and the rights of its students. Bethel College President Orville Voth was deeply skeptical. “Motivation must be in the name of Jesus Christ,” Voth said, “Political arguments are insufficient for committing our lives to.”6 Voth, however, was assuming two things that were not entirely true—first, that the students’ motivations were solely political; and, second, that political action and religious commitment were mutually exclusive. In reality, the motivations of many students were rooted in their Mennonite faith, which they saw as compatible with political action. Kirsten Zerger, a leader of the Peace Club at the time, reflected, “What I wanted to do was a Mennonite thing to do, but the church as an organization was not there.”7 Zerger was convinced that “the most powerful work is done when it’s multigenerational.”8 Bethel faculty also recognized this, as some participated in peace activities to show multi-generational concern and attempted to provide stability to the contentious situation. “I couldn’t understand my participation in these peace activities apart from my religious commitment,” Professor Alvin Beachy reflected, “If it weren’t for that, I wouldn’t have been involved. I can only see my action in terms of where I’m coming from.”9

While national media attention to these events was short-lived, the Peace Club’s actions in 1969 remained a relevant focal point for the controversial issues surrounding Vietnam among Mennonites. As was also the case in 1966, the Peace Club witnessed both their position on the Vietnam War to the state and their position on witness itself to the church. Peace activism among Mennonites spread quickly to Bluffton and Goshen Colleges, where students organized anti-war teach-ins, letter-writing events, and peace marches.10 The Bethel Peace Club and President Voth were contacted directly by Mennonites from around the country. Some were concerned with the national attention the events had generated. “It is unfortunate that this is the way millions of people have been introduced to Bethel College,” one critic lamented.11 On the other hand, some alumni praised the Peace Club and shared their feelings of pride when they saw the good work of Bethel students on the national news. Furthermore, a great deal of support for the Peace Club came in the form of monetary donations to fund future club activities.

The debate which surrounded the Peace Club’s activities can be understood as a microcosm of what was happening among Mennonites at the denominational level. In November 1969, the MCC Peace Section released a statement recognizing “noncooperation with military conscription as a valid expression of nonconformity and peacemaking.”12 By 1970, the Peace Section took a major step in establishing its new position on conscription, declaring that “the very existence of the draft contributes to the militarism that now dominates American life and threatens the freedom, stability and survival of the world.”13 Perhaps most exemplary of the change in the Mennonite conception of peace came from a statement issued by the General Conference Mennonite Church in 1971, which declared that “[peace] is much more than saying ‘no’ to war. It is saying a joyful ‘yes’ to a life of self-giving discipleship and evangelistic peacemaking,” and that “the Christian brotherhood should be involved in the decision and support of persons who disobey the law for conscience’ sake.”14 Boldly, the General Conference made a definitive shift away from their commitment to nonresistance toward one of active peace witness to society. The “Old” Mennonite Church also moved further away from nonresistance in their support of active peacemaking. In all cases, these changes were justified as a return to traditional Anabaptist theology.

It is here where we can circle back to the reflection stated earlier by a Mennonite in response to the Peace Club’s Moratorium Day demonstration. “When there is not a conflict like this here, people tend to settle down and forget about their major beliefs because they’re not pushed on them. But when they’re pushed on them, we have to do some of our best thinking.”15 Now, fifty years later, when active peacemaking has become a defining feature of Anabaptist-Mennonite faith and identity, this statement can and should still resonate with us. Yet, it is much easier to look back proudly on past events such as these and praise the progress we have made theologically and socially than it is to look at our current situation and find where changes still need to be made. People of faith, Anabaptist and otherwise, have never lived inside a vacuum. The students who pushed the edges of the Mennonite faith during in the 1960s were reinterpreting it in order to respond to the realities of their world. It seems that more and more our convictions are being pushed by political, social, and environmental forces, as well as by tensions which exist within the church itself. But how are we responding? Surely today’s world is changing, requiring from us a renewed Anabaptist vision, for our own sake, for the sake of the oppressed, and for the sake of all. Indeed, in situations of theological, social, and political conflict, we as a people of faith must do some of our best thinking, striving to face and address the challenges of the ever-changing world in which we live and witness.

- Mennonites and the Vietnam War: An Oral History, tape 41, tape recording, Mennonite Library and Archives, North Newton, KS (MLA).↩

- J. Harold Moyer, interviewed by Raymond Reimer, October 30, 1972, interview 30, tape recording, MLA. ↩

- Lynn Edwards to Peace Club, September 23, 1969, Bethel College Peace Club Papers, MLA.III.1.A 29.e, b. 1, f. 2, MLA. ↩

- Maynard Shelly, “Peace Walk Baffles Peace Church,” The Mennonite, December 13, 1966, 757-764. ↩

- Alvin Beachy, interviewed by Raymond Reimer, November 10, 1972, interview 31/32A, tape recording, MLA. ↩

- Quoted in Maynard Shelly, “For Us the Bell Tolled,” The Mennonite, November 4, 1969, 663. ↩

- Kirsten Zerger, interviewed by Dan Krehbiel, April 11, 2001, interview 83, tape recording, MLA. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Beachy. ↩

- Perry Bush, Two Kingdoms, Two Loyalties: Mennonite Pacifism in Modern America, (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 242. ↩

- Letter to Orville Voth, Bethel College Peace Club Papers, MLA.III.1.A 29.e, b. 7, f. 1, MLA. ↩

- Mennonite Central Committee Peace Section, A Message from the Consolation on Conscience and Conscription, November 22, 1969, in Urbane Peachey, ed., Mennonite Statements on Peace and Social Concerns, 1900-1978 (Akron, Pa.: Mennonite Central Committee U.S. Peace Section, 1980), 74. ↩

- Mennonite Central Committee Peace Section, The Draft Should Be Abolished, June 5, 1970, in Peachey, 75. ↩

- General Conference Mennonite Church, The Way of Peace, August 14-20, 1971, in Peachey, 145. ↩

- Mennonites and the Vietnam War. ↩

“Are you in this?” asked a popular British propaganda poster from the First World War. A nattily dressed young man, hands in pockets, walks through a landscape in which other men and women are actively fighting, nursing, and manufacturing armaments. Their society is fully engaged in war. His non-participation is clearly shameful.

“Are you in this?” asked a popular British propaganda poster from the First World War. A nattily dressed young man, hands in pockets, walks through a landscape in which other men and women are actively fighting, nursing, and manufacturing armaments. Their society is fully engaged in war. His non-participation is clearly shameful.

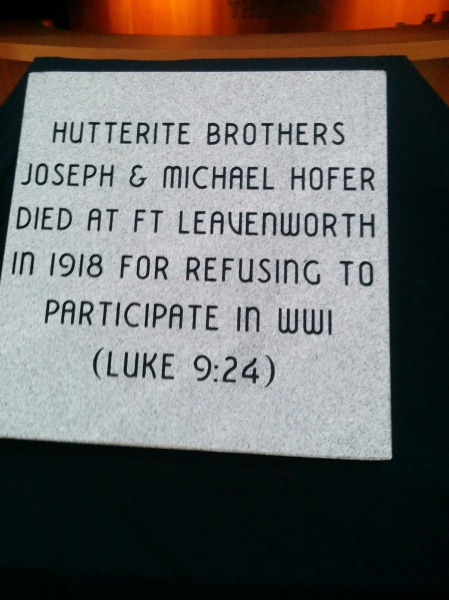

The World War’s profound effect on the United States is often overlooked. Although the United States actively took part in the conflict for only 18 months, the war effort introduced mass conscription, transformed the American economy, and mobilized popular support through war bonds, patriotic rallies, and anti-German propaganda. Nevertheless, many people desired a negotiated peace, opposed American intervention, refused to support the war effort, and/or even imagined future world orders that could eliminate war. Among them were members of the peace churches and other religious groups, women, pacifists, radicals, labor activists, and other dissenters.

The World War’s profound effect on the United States is often overlooked. Although the United States actively took part in the conflict for only 18 months, the war effort introduced mass conscription, transformed the American economy, and mobilized popular support through war bonds, patriotic rallies, and anti-German propaganda. Nevertheless, many people desired a negotiated peace, opposed American intervention, refused to support the war effort, and/or even imagined future world orders that could eliminate war. Among them were members of the peace churches and other religious groups, women, pacifists, radicals, labor activists, and other dissenters.