Jason B. Kauffman

Note: The following is an abridged version of a sermon I gave on Sunday morning, April 15, at Oak Grove Mennonite Church (Smithville, OH) during the congregation’s “Historical Reflections Weekend.” It was the first of three events planned for 2018 to celebrate Oak Grove’s bicentennial.

What does it mean to be the church together in a time of uncertainty and crisis?

Crisis is the stuff of history but, as a community of believers, conflict and confrontation often make us uncomfortable. We want to preserve harmony and unity at all costs so we don’t adequately address disagreements when they arise. It’s often easier if we just don’t talk about it.

But if the history of Christianity is any indication, conflict is unavoidable in the life of the church. In 1 Corinthians 3, Paul wrote to the early church in Corinth during a time of significant uncertainty. Factions and competing allegiances were developing and Paul wrote to remind them to put their trust in God instead of themselves.

This morning, I want to share another story of crisis that involved many people from the Oak Grove community. This is the story of the Young People’s Conference movement and its emergence during a watershed moment in the history of the (old) Mennonite Church in North America.[1] I’ll end by drawing some parallels between that story and the crisis that our denomination is facing today.

In the years following World War I, the institutional Mennonite Church was barely twenty years old and its growing pains were readily apparent.[2] The new denomination was in crisis over a polarizing conflict between traditional elements of the church and a new generation of reform-minded leaders.

One well-known example comes from Goshen College. Critics felt that the college was overly influenced by the modernist wave that had overtaken many other Protestant denominations. In 1905, the Mennonite Board of Education took oversight of the college to exercise closer control over its operations.[3] In 1923, ongoing financial troubles forced Goshen College to close for the academic year. Around the same time, Mennonite conference leaders in Indiana, Ohio, and Ontario revoked the credentials of multiple pastors deemed “at variance” with the church’s teachings on things like dress and the purchase of life insurance. In response, hundreds of people left their churches and joined other congregations from the General Conference Mennonite Church. Others left the Mennonite church altogether.

It was within this context that the Young People’s Conference movement was born. Its leaders included many from Oak Grove, including Jacob Conrad Meyer, Vernon Smucker, and Orie Benjamin Gerig. They were part of a new generation of Mennonite men and women who came of age during these first few decades of conflict in the church. Many graduated from Mennonite colleges and embraced new initiatives in home evangelism and overseas missions.

Portrait of Jacob Conrad Meyer taken in 1917, shortly before he left for France. MC USA Archives

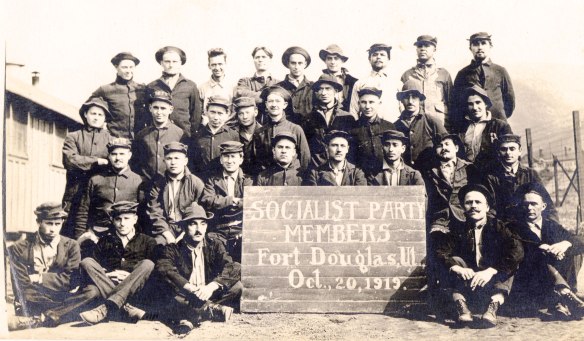

More importantly, they came of age during World War I, the deadliest war in history to that point. During the war, hundreds of Mennonite men lived in work camps as conscientious objectors. Many felt abandoned by denominational leaders who they believed had not equipped young people to face the challenges of being a CO during wartime. They also came away with a renewed conviction that the church should adopt a more outward focus, one centered on service, peace, and engagement with the rest of the world.

After the war, several dozen young Mennonites acted on this conviction by volunteering to assist the reconstruction efforts in France. Here they gained firsthand exposure to the destruction of war. They also met regularly to discuss their concerns about the Mennonite Church. One of the key organizers for these meetings was Jacob Conrad Meyer. He and others became increasingly critical of what they saw as weak leadership and lack of support for the concerns of younger members.

Attendees at the first Young People’s Conference in Clermont-en-Argonne, France, June 20-22, 1919. MC USA Archives

Eventually, these relief workers organized the first Young People’s Conference at Clermont-en-Argonne in June 1919. At the end of the conference, they produced a list of priorities for the “church of the future.”[4] They also drafted a constitution and elected an executive committee to provide leadership for the emerging movement. Of the six committee members, three were from Oak Grove: Vernon Smucker, J.C. Meyer, and O.B. Gerig.

However, the YPC movement was short-lived. After returning to the United States, leaders planned and organized three annual meetings between 1920 and 1923. But the movement faced steady opposition from denominational leaders who accused its leaders of unorthodox theology. Ultimately, the YPC movement couldn’t convince church leaders that it sought to work with rather than against them. By 1924, the movement was over.

How should we interpret the failure of this movement?

In 1 Corinthians 3:11-13, Paul writes: “For no one can lay any foundation other than the one already laid, which is Jesus Christ. If anyone builds on this foundation using gold, silver, costly stones, wood, hay, or straw, their work will be shown for what it is, because the Day will bring it to light. It will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test the quality of each person’s work.”

For those involved in the YPC movement, its failure after just a few years must have been a big disappointment. Here were young, intelligent leaders ready to offer their gifts to the work of the church, only to see their ideas met with suspicion and rejection. Indeed, O.B. Gerig was so disillusioned that he left the Mennonite church entirely. In a letter to J.C. Meyer in 1921, Gerig wrote, “I have come to the point where I can no longer view all problems only in the light of our own little branch of the church. We have a larger project in view. In the end, our plan will live after all their intrigue has passed on the blemished page of history.”[5]

As we now know, Gerig’s words turned out to be prophetic. One hundred years later, most of the reforms that the YPC movement advocated have been implemented.[6] Indeed, many have become central to the identities of multiple generations of Mennonites who grew up during the twentieth century. For example:

- The YPC wanted the church to take a proactive stance with the U.S. government on issues of peace and conscientious objection to war. In the 1930s, the denomination worked with leaders from other historic peace churches and the government to create the Civilian Public Service program. During WWII thousands of Mennonites served with CPS as an alternative to military service and active peacebuilding remains a key focus for Mennonites today.

- The YPC called for a stronger emphasis on service and relief to those in need. Over the course of the twentieth century Mennonite Central Committee has emerged as one of the most highly respected inter-Mennonite institutions in North America and abroad.

- The YPC called for more dialogue between Mennonites of different national and cultural traditions. Today, Mennonite Mission Network continues its good work and Mennonite World Conference brings together people of Anabaptist faith from across the globe.

It took the fresh eyes of new leaders to articulate a new vision for the Mennonite Church in a complex and changing world. Through these young people, God planted a seed. Over the last 100 years, you at Oak Grove have watered that seed, dedicating your lives to the work of Christ in both large and small ways. Back in 1918, and even more so in 1818, the future of the Mennonite Church was anything but clear, but God has been faithful and God—not us—caused the seed to grow.

Today we are entering a new phase of uncertainty in the history of the Mennonite community in North America. Like the church 100 years ago, our newly merged denomination—Mennonite Church USA—is less than 20 years old and the growing pains are readily apparent. Our Mennonite colleges and universities are struggling financially. Our missions, service, and publishing agencies have drastically reduced operations in the last few decades. And our denomination is experiencing a rapid decline in membership, including the departure of entire conferences. As in 1918, the current crisis grows from a conflict based largely upon differing views regarding the kind of church Christ is calling us to be.

Last summer, MC USA organized the Future Church Summit at the bi-annual convention in Orlando. The goal of the summit was to gather voices from across the denomination to identify core convictions and chart a new course for the church. One tension that I observed throughout the FCS was between denominational leaders—usually heritage Mennonites, usually middle aged—and younger participants, many of whom did not grow up in the Mennonite church.

I heard resentment from younger leaders about the unwillingness of the “old guard” to let go of control. And I heard older participants lament the exodus of young people from the church and their “indifference” and lack of commitment to MC USA and its ministries. But I was also impressed by the many articulate and passionate young leaders who are committed to working for positive change from within the denomination. Their words echoed many of those voiced 100 years ago at Young People’s Conferences. They were filled with the same optimism, energy, and hope.

It is a fact that church attendance among Mennonites and many other denominations is declining. Many young people no longer see the church and its institutions as relevant parts of their lives. Yet, as I look out over the pews, I am struck by the number of young people and children here at Oak Grove. So, in closing, I want to speak to you and leave you with a few questions.

Why have you chosen to stay connected to the church? What about Oak Grove made you want to invest your lives in this community? Now, more broadly, what is important to you about being Mennonite? What is your hope for the future of the church…here in Wayne County, in North America, and around the world? Do we still need institutions like MC USA, MMN, or MCC to help us do the work of God in the world? I would argue yes. These institutions connect what is now a truly global church and allow us to accomplish much more of Christ’s work than we could on our own.

But these are tough questions, ones that I continue to struggle with as a 35-year-old Mennonite by choice. As you seek answers, I challenge you to take inspiration from Oak Grove’s history and consider the “cloud of witnesses” that has gone before you. For 200 years, the community of believers gathered at Oak Grove has found a way to remain in fellowship, even in the midst of crisis. In 100 years, how will your grandchildren and their children look back on you? What will you do to help continue this work? We aren’t perfect and we will make mistakes but I pray that we will “run with perseverance the race marked out for us, fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of faith.”

[1] Originally an Amish Mennonite community, Oak Grove was part of the Eastern Amish Mennonite Conference from 1893 until 1927 when the conference merged with the Ohio Mennonite Conference to form the Ohio Mennonite and Eastern Amish Mennonite Joint Conference (later the Ohio and Eastern Mennonite Conference), affiliated with the “old” Mennonite Church. From 1947 to 1970, Oak Grove held no conference affiliation. In 1970 the congregation became a dual affiliate of the Ohio and Eastern Mennonite Conference and the Central District Conference of the General Conference Mennonite Church. The Young People’s Conference movement engaged leaders mostly from the “old” Mennonite Church.

[2] Before the establishment of the General Conference Mennonite Church in 1860 and the (old) Mennonite Church in 1898, Mennonite communities in North America functioned mostly as a loose association of local districts and conferences without any centralized institutions.

[3] Most of the context and background for this section comes from a well-researched essay by Anna Showalter, “The Mennonite Young People’s Conference Movement, 1919-1923: The Legacy of a (Failed?) Vision,” The Mennonite Quarterly Review 85:2 (April 2011), p. 181-217.

[4] The full list is printed in Showalter, “Mennonite Young People’s Conference Movement,” 196.

[5] Ibid., p. 182.

[6] Anna Showalter and James O. Lehman make this same point in their analyses of the YPC. See Showalter, 212-217, and James O. Lehman, Creative Congregationalism: A History of Oak Grove Mennonite Church in Wayne County, Ohio (Smithville, OH: Oak Grove Mennonite Church, 1978), 211-212.

“Are you in this?” asked a popular British propaganda poster from the First World War. A nattily dressed young man, hands in pockets, walks through a landscape in which other men and women are actively fighting, nursing, and manufacturing armaments. Their society is fully engaged in war. His non-participation is clearly shameful.

“Are you in this?” asked a popular British propaganda poster from the First World War. A nattily dressed young man, hands in pockets, walks through a landscape in which other men and women are actively fighting, nursing, and manufacturing armaments. Their society is fully engaged in war. His non-participation is clearly shameful.

The World War’s profound effect on the United States is often overlooked. Although the United States actively took part in the conflict for only 18 months, the war effort introduced mass conscription, transformed the American economy, and mobilized popular support through war bonds, patriotic rallies, and anti-German propaganda. Nevertheless, many people desired a negotiated peace, opposed American intervention, refused to support the war effort, and/or even imagined future world orders that could eliminate war. Among them were members of the peace churches and other religious groups, women, pacifists, radicals, labor activists, and other dissenters.

The World War’s profound effect on the United States is often overlooked. Although the United States actively took part in the conflict for only 18 months, the war effort introduced mass conscription, transformed the American economy, and mobilized popular support through war bonds, patriotic rallies, and anti-German propaganda. Nevertheless, many people desired a negotiated peace, opposed American intervention, refused to support the war effort, and/or even imagined future world orders that could eliminate war. Among them were members of the peace churches and other religious groups, women, pacifists, radicals, labor activists, and other dissenters.