Fascism often begins with sex. It can rely especially on anxieties about men of color having sex with white women.1 The pattern holds for Mennonite fascism, a specifically Anabaptist political philosophy modeled on Nazism that during the 1930s found support among German-speaking Mennonites around the world. While there are many sides to Mennonite fascism, I will focus here on the writings of J.J. Hildebrand—a Winnipeg-based immigrant from the Soviet Union who in 1933 proposed the formation of a fascist “Mennostaat,” or Mennonite State.2 This tale unfolds in a moment of global uncertainty, in which the legacies of the First World War and the shock of the Great Depression had sent democracy into retreat. Strongmen like Hitler and Mussolini drew praise even in places like Great Britain or the United States, and for many Mennonites, fascism’s unabashed racism seemed both to explain why their church had experienced so much persecution and also to offer a buffer against fresh assaults.

J.J. Hildebrand, Mennonite fascist, ca. 1930. Credit: J.J. Hildebrand Collection, Photograph Ca MHC 303-6.0, Mennonite Heritage Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba

Enter J.J. Hildebrand: a successful businessman born in Ukraine, a longtime advocate for Mennonite rights, and an avid observer of Nazi Germany. Emigrating to Canada after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Hildebrand had spent the following decade promoting various settlement schemes for anti-Soviet coreligionists who, like himself, were seeking both refuge from communism and economic security in their new American homelands. According to Hildebrand, Mennonites constituted a pure-blooded “nation” or “race” that, since arising in Central Europe 400 years previously, had become scattered across the earth. Dispersed among foreign populations whom he described as Russian, Persian, Chinese, Mongolian, Polish, Mexican, Paraguayan, and Brazilian, members of the faith supposedly faced a global plague of racial defilement, that if continued, might lead to their ultimate demise. Writing for the widely-read Canadian denominational paper, Mennonitische Rundschau, or “Mennonite Review,” Hildebrand emphasized the danger to his readers: “our Mennonite girls—to which we, Mennonite men, have the first and only right, and whom we approach only via the honest path to the altar—are now exposed to the sexual caprices of these and similar types.” Such a reality “makes my Germanic blood boil,” Hildebrand explained. “Yours too?”3

One can imagine the fifty-three-year-old Hildebrand in his Winnipeg office—fully bald, dark-rimmed glasses framing a face he fancied “Germanic”—fantasizing about the Mennonite girls whose sexuality he considered the property of his kind. The issue held significance against the recent backdrop of mass immigration from Eastern Europe; in contrast to the wealth and power of Anabaptist life in formerly tsarist Russia, many new arrivals faced unaccustomed hardship, to which hundreds of families responded by sending their daughters to perform domestic labor in Canadian cities.4 What bothered Hildebrand was not just the thought of brown men in dark alleyways forcing themselves on defenseless white women, as the racist stereotype held, but more insidiously the possibility that inter-ethnic relationships might be consensual—that Mennonite women in the diaspora might be led astray, allowing their wombs and thus their bloodlines to be lost to the race. Indeed, race: Hildebrand thought of Mennonitism as a distinct racial category, interwoven by centuries of intermarriage. A Native American or Indonesian convert—or even the Canadian “English”—could never be Mennonite in this sense. “There are no Slavic, Latin, Anglo-Saxon, Indian, Malayan, Chinese, or Japanese Mennonites,” Hildebrand wrote. Even if converts practiced adult baptism, foot washing, opposition to oaths, and nonresistance, they would only be Christians. Mennonitism stemmed “from our racial origins.”5

How to ensure that Mennonites preserved their racial stock, that the right women bred with the right men? Hildebrand’s solution was the formation of a Mennonite State. Envisioning the “collection of our race from across the entire globe,” he proposed the establishment of an autonomous, self-administered territory. The initial sketch was vague enough to be humorous: the world’s 500,000 Mennonites could build a homeland on, say, one to seventeen islands. Their official languages would be Low and High German. Their currency, the Menno-Gulden would be pegged to the gold standard and worth 25 US cents. Each family would be given 120 acres to farm, and each household would elect one representative to the local “district assembly.” Every district assembly (each with around 100 members representing 1,000 families) would then elect two representatives to the “state assembly.” To fund the venture, Hildebrand recommended that proponents donate to a hypothetical “Menno-Collection-World-Union.” Contributors would each wear small medallions showing doves with peace palms against a blue field—“external signs” reminiscent of Nazi armbands.6

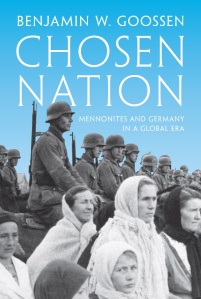

My new book explores the origins, nature, and consequences of Mennonite fascism

Easily the oddest detail here is Hildebrand’s inclusion of the peace dove. All the other elements conform to the typical trappings of 1930s-era fascism. Racial utopias and agrarian settlements were hallmarks of fascist movements across Europe and the Americas, as was the general activity of planning the obscure details of future political and economic systems—from which certain groups, usually Jews, would be excluded. Even the concept of an island state held fascist connotations. At least some readers of the Mennonitische Rundschau, where Hildebrand’s piece appeared, were familiar with books like Aryan Race, Christian Culture, and the Jewish Problem (1931), an anti-Semitic pamphlet that advocated removing the world’s Jews from their countries of residence and sending them to Madagascar.7 Despite frequently comparing themselves to Jews (in fact Hildebrand conceived his Mennonite State as a “solution” to the “Mennonite Problem,” language evoking contemporaneous efforts to “solve” the so-called Jewish Problem), Mennonite newspapers and institutions across Canada and beyond were rife with anti-Semitism.8

But what about the dove? What made Hildebrand’s proposal absolutely unique in the history of political philosophy was that it represented a strange but surprisingly popular brand of pacifist fascism. The “Mennonite Problem” that Hildebrand hoped to solve was certainly about persecution, sex, and racial defilement. It was also about military service. While nonresistance had been a major tenet of Anabaptist thought until the nineteenth century, the rise of mass conscription and especially the events of the First World War had quite literally brought the principle under fire. “Peaceful coexistence of nations,” Hildebrand wrote, “the peace ideal—this Mennonite cultural inheritance—has been packed away in the travel trunk for protection, and in many states our freedom from military service has been trod under foot.” With yet more wars and revolutions looming on the horizon, Hildebrand believed that as long as Mennonites lived in militarist states, their pacifism would not survive the night. The state “sends the police into our homes to conscript our sons for war; it sends the police to confiscate our horses, wagons, grain, and more for war; it dictates the impossibly high taxes to cover the costs of war.”9

Hildebrand’s idea of a “peace island” inspired discussion among Mennonites across Canada and beyond.10 Over the following year, his proposal generated a lively debate in the denominational press about the feasibility and desirability of establishing a separatist Mennonite State. “Where is it supposed to be built?” wondered one skeptic, before going on to lay out the difficulty of gathering a half million Mennonites from a dozen countries, convincing them all to live and work together, and then going about the tricky business of setting up a bureaucracy and establishing diplomatic relations with other countries. “And would we eventually have communists among us?” he went on. “What do we do with them? Gently reprimand them? Or throw them out so that they go to our neighbors and turn them against us? Or perhaps condemn them to death?” Some issues generated laughter. Would mustaches be banned in the Mennonite State? But the most serious concerns revolved around military service: how could a pacifist state ensure its independence without eventually raising an army—and thus abandoning nonresistance? In the case of an invasion, foreign occupiers might, ironically, “also be interested in our beautiful girls, so that Hildebrand’s Germanic blood may once again be brought to a boil.”11

The Mennonite State never materialized—at least as Hildebrand imagined. Brushing aside questions of feasibility, he reasoned that although an independent Poland had seemed impossible before the First World War, the conflict had forged nearly overnight this improbable victory. As for small, defenseless states that managed to avoid military engagement, Hildebrand dove into the history and political structures of Switzerland, Andorra, San Marino, and Monaco. The dreamer went so far as to reach out to foreign governments about granting “complete, treaty independence” for possible Mennonite States across Africa, Latin America, and Oceania. One response from Australia informed Hildebrand that his request was “quite impossible.12” Political will was also lacking within the denomination. This wariness reflected, in part, a skepticism of Hildebrand himself. Although prominent, wealthy, and relatively well-connected, Hildebrand had never been quite as influential as he would have liked. If many commentators felt a Mennonite State was in theory possible, constructing it would require a feat worthy of a Moses or a Hitler. “In any event, Hildebrand is not this Moses,” one personal acquaintance assessed. “He may have Führer ambitions and Führer desires; Führer talent he does not have.”13

When viewed from the long arc of Anabaptist history, it is perhaps tempting to dismiss Mennonite fascism as a hapless anomaly. “Why don’t we relegate ‘the Mennonite State’ to the archive…?” suggested the editor of the Mennonitische Rundschau in an exasperated aside after one of Hildebrand’s more fanciful articles. “All in favor, raise your hands!”14 By April 1934, the matter seemed sufficiently closed that another author could refer to Hildebrand’s intervention as “unhappy and somewhat erstwhile.”15 Nevertheless, the Mennonite State was not a laughing stock. And Hildebrand was a serious enough figure to spark thoughtful debate. Consider the 1935 response of B.B. Janz, a prominent Mennonite Brethren church leader—and also an immigrant from the Soviet Union—who criticized Hildebrand’s proposal not for its implausibility but because it hit too close to home. “But wait,” Janz wrote, “we have already attempted the Mennonite State, whole hog.”16 Referring to the large semi-autonomous Mennonite settlements in the Black Sea region of the former Russian Empire, Janz noted that for more than one hundred years, Mennonites had exercised judicial, administrative, and educational independence. And what had it wrought? In his telling, conflict upon conflict—from tax and land issues to the persecution of one new religious movement after another: the Kleine Gemeinde, the Mennonite Brethren, the Templers.

Mennonites in Canada, especially recent immigrants from the Soviet Union, often praised the Third Reich or modified fascism for their own purposes. Here, a Mennonite choir performs at a Nazi rally in Manitoba. “Hitler Salute: Local Germans Hail Re-birth of Fatherland Under Fuehrer,” Winnipeg Free Press, January 30, 1939, 1.

Whether or not B.B. Janz was right about the deleterious nature of Mennonite administration in old Russia, during the years between the World Wars, he was surely in the minority of Mennonites from Eastern Europe who did not think back on the settlements with fondness. “As I was still a boy, I often and gladly looked over the green gardens and forest-filled villages of the Molotschna [colony],” volunteered a more nostalgic writer. “I loved the whole settlement, containing the whole Mennonite nation as I knew it. At that time, I too dreamed of the formation of a country where no Russian or anyone else would order us about and where Mennonitism could unfold in its full glory.”17 Stripped of their wistful sheen, such notions found deep resonance in the new imperial projects of European fascists—movements that shared Hildebrand’s racism but whose power was far greater. “Germany is fighting for its rehabilitation and for its lost colonies,” reported an Ontario-based author in the Mennonitische Rundschau. “And when this moment arrives, then we may hope that we will be incorporated into that country, whose sons and daughters we are, whose spirit is our spirit, whose blood is our blood—as an independent Mennonite colony under German protection.”18

Visions for racially homogeneous Mennonite settlements under fascist rule found realization in Nazi-occupied Ukraine. Here, Heinrich Himmler (third from right), head of the SS and an architect of the Holocaust, at a flag raising in the Molotschna Mennonite colony, 1942

Why care about Mennonite fascism? One answer is that it was far more widespread than has generally been recognized. Well beyond statist debates in the Mennonitische Rundschau, similar ideas found adherents and interlocutors among populations across Europe and the Americas. Some pockets were remote and unexpected. Schoolchildren in Paraguay’s Gran Chaco, for example, could read about “Mennonites as Genealogical Community” in one biology textbook: “They form a large family or clan. In their veins flows the same German blood.”19 In other contexts, the ideology’s influence was monumental. Across the ocean in the Third Reich, Mennonites found a special place in Nazi racial theory. During the Second World War, when Hitler’s armies conquered large swaths of the Soviet Union, prominent fascists visited, praised, and supported the large German-speaking Mennonite colonies in occupied Ukraine. Harrowing experiences under communism had prepared the way for a warm reception. “I was no enemy of the Soviets,” one local explained to Nazi occupiers, “but now that I’ve come to know them, you’ll find I’m a true enemy. Now I’m a Hitlerite, a fascist unto death.”20

Mennonites in Eastern Europe generally collaborated with Nazi colonizers—if not always fully supporting their ideology or policies, as historian Aileen Friesen explains in a recent post. While occupiers built up local settlements like Chortitza and Molotschna, providing aid and services not dissimilar from the visions of Hildebrand and his supporters, death squads—some with Mennonite members—massacred nearly all of Ukraine’s 1.2 million Jews, including tens of thousands in and around the Mennonite colonies. This is what fascism looked like in its rawest form. Hildebrand’s “peace island” was indeed an unachievable fantasy, but not because there was insufficient will to produce a racially-pure utopia. It was a fantasy because fascism is always built on racial exclusion—and hate is inherently violent. J.J. Hildebrand himself spent the Second World War in Allied Canada. While he was a decorated member of the Nazi German Canadian League, he did not personally participate in ethnic cleansing. Yet whether in democratic Canada, rural Paraguay, or the Third Reich, Mennonite fascism was never innocuous. Listen to the second stanza of Hildebrand’s proposed anthem for the Mennonite State, set to the tune of Germany’s own national song:

Our girls among foreigners

become ever more lost to us

Who however for our young men

alone have been predestined.

Have you for our girls

not a dear warm heart?

To wrest them from the yellow to-

bacco chewer’s unwelcome jape?21

Lest we think that peace theology alone shields us from the dangers of racial nationalism, let it be said: pacifists can be fascists, too. In the 1930s and 1940s there were plenty of Mennonite fascists, pacifist or otherwise. As a denomination we have not yet come to terms with this past, nor have we fully examined which elements of Mennonite fascism slipped past the end of the Second World War, which snippets of our theology and worldviews remain influenced by the once prominent drive for Germanic racial purity in many Mennonite congregations. Paraguayan biology classes, to name one example, continued referring to Mennonites as a blood community well into the postwar years, while in Germany, a popular Mennonite history book authored by a former Nazi and emphasizing genealogical transmission remained in print as recently as 1995.22 In North America, too, we frequently hear claims that Anabaptism is a German religion or that Mennonitism constitutes a family church. Violence and exclusion, including oppressive uses of peace theology, can be tied up in such claims. We should ask: who is marginalized, demonized, or rejected in our own congregations—whether in the name of religion, nation, immigration status, or sexual orientation?

Were J.J. Hildebrand writing today, he would undoubtedly see justification for new nativist projects in the right-wing populism sweeping Europe, the United States, and the world. Nor would he be alone. Fascism as a self-conscious movement is once again gaining prominence. Indeed, immigration restrictions in the United States, power grabs in Asia and Latin America, and refugee backlash in Europe—along with a shocking spate of anti-Semitism, anti-Islamic sentiment, homophobia, and Holocaust denialism in both official and unofficial places—demonstrate that in essence, if not in formal name, the logic at fascism’s core already holds political power.

Mennonites are not immune.

This article draws on research conducted for my book, Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, out this month from Princeton University Press. Thanks to Uwe Friesen, Rachel Waltner Goossen, Conrad Stoesz, John Thiesen, James Urry, and Madeline Williams for their assistance.

- For a brief introduction to fascism, see Robert Paxton’s excellent, The Anatomy of Fascism (New York: Random House, 2007). On fascism and sex, see Dagmar Herzog, Sex After Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-Century Germany (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 10-63. ↩

- The most extensive treatment of J.J. Hildebrand and his Mennostaat proposal is James Urry, “A Mennostaat for the Mennovolk? Mennonite Immigrant Fantasies in Canada in the 1930s,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 14 (1996): 65-80. For Hildebrand’s context among recent Mennonite immigrants to Canada between the World Wars, see James Urry, Mennonites, Politics, and Peoplehood: Europe—Russia— Canada, 1525 to 1980 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2006), 185-204. On the Mennonite paper, Die Mennonitische Rundschau, in which Hildebrand published his proposal, see Harry Loewen and James Urry, “A Tale of Two Newspapers: Die Mennonitische Rundschau (1880-2007) and Der Bote (1924-2008),” Mennonite Quarterly Review 86, no. 2 (April 2012): 175-204. On the generally German nationalist orientation of the immigrant Mennonite press in 1930s Canada, see Frank Epp, “An Analysis of Germanism and National Socialism in the Immigrant Newspaper of a Canadian Minority Group, the Mennonites, in the 1930’s” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1965). ↩

- J.J. Hildebrand, “Zeichen der Zeit!” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, March 29, 1933, 4. ↩

- Marlene Epp has emphasized how Mennonite immigrant families and church communities generated anxieties around the sexual safety of female domestic laborers while also asserting patriarchal control over these women’s movements and earnings: Mennonite Women in Canada: A History (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2008), 42-51. ↩

- J.J. Hildebrand, “Mennonitische Geschichte: 60 Jahre später,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, March 28, 1934, 2. For Hildebrand’s views of many non-Mennonite Canadians as racially “English,” see J.J. Hildebrand, “Our Flag is One Thing. Our Race is Another,” Winnipeg Free Press, November 27, 1937, 24. ↩

- Hildebrand, “Zeichen der Zeit!” 5-6 ↩

- Egon van Winghene, Arische Rasse, Christliche Kultur und das Judenproblem (Erfurt: U. Bodung-Verlag, 1931). For a Mennonite review, see A. Kröker, “Zum Judenproblem,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, March 14, 1934, 2-3. On van Winghene’s book and its context, see Magnus Brechtken, Madagaskar für die Juden (Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1997), 38-42. ↩

- On Nazi sentiment among Mennonites in Canada, see Frank Epp, “Kanadische Mennoniten, das Dritte Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg,” Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter 31 (1974): 91-102; Benjamin Redekop, “Germanism Among Mennonite Brethren Immigrants in Canada, 1930–1960: A Struggle for Ethno-Religious Integrity,” Canadian Ethnic Studies 24 (1992): 20-42 ↩

- Hildebrand, “Zeichen der Zeit!” 5-6. ↩

- Argus, “O x O burg,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, May 10, 1933, 12. ↩

- Incertus [probably elder Jacob H. Janzen], “Zur Hildebrand-Utopie,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, May 10, 1933, 11. ↩

- Quotations from Urry, “A Mennostaat,” 65 ↩

- Incertus, “Zur Hildebrand-Utopie,” 11. ↩

- J.J. Hildebrand, “Ueber Mennostaat,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, May 10, 1933, 14. ↩

- B.W., “Wanderungen,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, April 4, 1934, 2 ↩

- B.B. Janz, “Woher und Wohin: Streiflichter auf die mennonitischen Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, April 10, 1935, 3. ↩

- J.B.W., “Mennonitisches Problem,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, April 26, 1933, 4. ↩

- B.W., “Wanderungen,” 2. ↩

- Naturkunde, Erdkunde, Täufer und Mennonitengeschichte für die Volkschulen: 6. Schuljahr (Philadelphia, Paraguay; Druckerei “Menno-Blatt,” 1943), 17. ↩

- Franz Hamm, “Schilderung des Volksdeutschen Franz Hamm über ein Jahr Gefängnisleben,” March 8, 1942, T-81/606/5396745-51, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. ↩

- J.J. Hildebrand, “Zu meinen ‘Zeichen der Zeit,’” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, April 19, 1933, 12. ↩

- Naturkunde für die mennonitischen Volksschulen, 5.-6. Schuljahr (Philadelphia, Paraguay: Druckerei “Menno-Blatt,” 1954), 32-33; Horst Penner, Horst Gerlach, and Horst Quiring, Weltweite Bruderschaft: Ein mennonitisches Geschichtsbuch, fifth edition (Kirchheimbolanden: GTS-Druck, 1995). ↩

Excellent article. Thanks for helping to tell the full story, Ben.

LikeLike

In Goossen’s reductionist worldview, individuals and states have moral legitimacy. Civil society–that chaotic patchweork of communities defined by shared experience, language/culture, moral commitment or religious vision–merely pretends to legitimacy by masking exclusionary (“fascist”) identities. It’s a parlor game of “let’s pretend” that is quite trendy among liberal Mennonites, who want to delegitimize notions of “community” and to create a “church” that looks and acts like an equal-opportunity social improvement association. But it obscures as much as it reveals.

I’ve just spent nine days in Poland, the place where the diverse converts to Anabaptism became over the course of 400 years “germanic” Mennonites. It is an important story of identity, one that played out tragically in Poland and Russia during the ’30s and ’40s. So Goossen’s work with this history could be very useful, if only he didn’t so enthusiastically put his historical research in service of his impoverished, liberal ideology.

LikeLike

I am glad that this article makes you and many other Mennonites uncomfortable.

LikeLike

So well said, Berry.. I could not agree more.

The increasing domination of academia by forces completely hostile to the Western (and certain Mennonite) tradition has churned out countless examples of extreme bias. It’s heartbreaking to watch.

A trustworthy people are that much more naive and gullible for it, as they see the entire world in their own image, and have difficulty sorting and sifting truth from lie. I feel we suffer from this to the extreme, and long for the day when we’re able to take a more intellectually honest approach to such issues/questions.

From a fellow Friesen: I appreciate your post!

LikeLike

A sad part of our history. It certainly does not reflect the Mennonites I know and love today.

I am wondering what the value of putting it on Facebook achieves. In a society that digests mostly soundbites and forms it’s opinions on those, “Mennonites are Facists” is what will stick in their minds.

LikeLike

The origin of Swiss Anabaptism was the idea that there can be “Free Churches”, i.e. that there can be communities who are mutually exclusive and notwithstanding live peacefully beneath each other. This idea has informed not only European Church History but European Political History, too.

Goossen’s opinion that exclusion is always violent and thus there must never be any exclusivity – that practically tries to revoke the genuine idea of Swiss Anabaptism.

LikeLike

By the way, if Goossen thinks that

“racial utopias and agrarian settlements were hallmarks of fascist movements across Europe and the Americas, as was the general activity of planning the obscure details of future political and economic systems”,

what does he make with Zionism (which was partly promoted to avoid the rising danger of exogamy)? And Zionism was obviously the most successful of all these plannings! But Goossen seems to dodge this question.

LikeLike