Recent scholarship has illuminated the hitherto little-known involvement of Mennonites in the perpetration of the Nazi Holocaust of European Jews and other atrocities committed during the Second World War. While historians have begun to describe the overall shape of Mennonite participation in war crimes, and although numerous individual stories continue to come to light, the details of how specific Mennonite communities interacted with many of the Nazi state’s killing operations have yet to be clarified. This essay offers one possible model for such studies. It examines the involvement of Mennonites in the Waffen-SS, particularly the activities of a cavalry regiment totaling about 700 men in the Halbstadt colony in Nazi-occupied Ukraine.1

Mennonites in Germany had participated in the SS well before the outbreak of the Second World War. Some rose in the ranks, thus holding leadership positions as the Holocaust and other war atrocities began. Jakob Wiens, an agricultural office assistant in Tiegenhof, for instance, joined the SS in 1932. Wiens transferred to the Waffen-SS when Nazi Germany invaded Poland, and in 1941 he headed a requisitions group in Tarnow as local Jews were forced into a ghetto. Following the invasion of Ukraine, Wiens managed a center for clothing distribution in Dnipropetrovsk, likewise a site of expropriation and murder.2 Once in Ukraine, Waffen-SS members like Wiens often came into contact with the region’s large German-speaking Mennonite population. One SS-Hautpsturmführer, Günther Fieguth, published a feature article in the newspaper Danziger Vorposten about such encounters. In addition to recognizing common surnames and making genealogical connections, Fieguth lauded the Third Reich for aiding local Mennonites “to once again stimulate the blossoming racial life of this German population.”3

Nazi Germany’s military expansion into Eastern Europe presaged enormous recruitment efforts for the Waffen-SS. The organization had begun in 1933 as the armed branch of the SS, an elite core of soldiers who served as Adolf Hitler’s bodyguard. The Waffen-SS was marked by its militancy and loyalty to the Führer, including perpetration of a violent purge of the rival SA in 1934. With the outbreak of war at the end of the decade and access to populations in Eastern Europe, the Waffen-SS radically expanded. The occupied territories ultimately supplied more than half of the nearly one million men who served in the Waffen-SS at its height.4 Recruiters opened their ranks to men of a variety of perceived racial backgrounds, but they favored people they considered to be German, even if they did not yet possess German citizenship. Such individuals were known within Nazi racial terminology as “ethnic Germans” (Volksdeutsche).

Hitler intended “ethnic Germans” to be treated as a master race in Eastern Europe. One directive to occupational authorities read:

When girls and women of the occupied Eastern territories abort their children, then that can only benefit us. . . . since we have absolutely no interest in the growth of the non-German population. . . . Therefore also under no condition should German healthcare measures be provided to the non-German population in the occupied Eastern territories . . . . In no way may the non-German population receive advanced education . . . . Under no circumstances will the Russian (Ukrainian) cities be improved or even beautified, since the population should not reach a higher level, and the Germans will live in new cities and towns to be built later, from which the Russian (Ukrainian) population will be strictly prohibited. 5

The Waffen-SS counted among the numerous Nazi organizations charged with achieving this vision. In 1941, Himmler formed an SS Cavalry Brigade for deployment in Belorussia and northern Ukraine. Jews and others considered racially inferior were marked for immediate destruction: “If the population, treated on a national basis, is composed of hostile, racial and bodily inferior criminals… then all who are implicated in helping partisans are to be shot; women and children are to be deported; livestock and food are to be requisitioned and brought to safety. The villages are to be burned to the ground.”6 This SS Cavalry Brigade engaged in the mass execution of Jews, helping initiate the wholesale slaughter of the Holocaust in the East.7

While Ukraine’s Mennonites entered the Waffen-SS in various ways, the most notable induction occurred in the largest Mennonite colony of Molotschna, renamed Halbstadt by the occupying forces. During the first year of German occupation, Halbstadt remained located in the war zone and thus fell under SS administration rather than under civil jurisdiction of the new Reich Commissariat Ukraine. Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, tasked a group called Special Commando R (“R” for Russia) with overseeing “ethnic German” affairs in areas conquered from the Soviet Union, including Halbstadt. Although Special Commando R’s main objective was to provide welfare to local “ethnic Germans,” its instructions as part of Himmler’s Ethnic German Office included cooperation with the mobile SS killing units known as the Einsatzkommandos.8 Through this partnership, Special Commando R and its “ethnic German” associates participated in the mass murder of tens of thousands of Jews and other victims across Eastern Europe.

Ukraine’s approximately 35,000 Mennonites comprised slightly more than ten percent of the 313,000 “ethnic Germans” that Nazi occupiers counted in German-occupied Ukraine, Romanian-occupied Transnistria, and the nearby war zone.9 Around 25,000 “ethnic Germans,” of which a majority were Mennonites, lived in the more than ninety villages of the Halbstadt colony. Special Commando R reported that to a higher degree than in more western regions, “the German settlements of Mennonites on the Molotschna [River] and in the Gruanu area (Mariupol) have been evacuated and destroyed by the Bolsheviks.”10 Communist authorities had deported around half of Halbstadt’s residents beyond Soviet lines on the eve of the German invasion. Less than a third of remaining adult “ethnic Germans” were male. Special Commando R began organizing 1,200 of the colony’s men and boys into paramilitary “Self Defense” units, a practice typical within German-speaking settlements across Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe.11

The first steps toward the induction of Halbstadt Mennonites into the Waffen-SS began in the context of jurisdictional disputes between the German Army and the SS. The Army had been recruiting local Mennonites to serve as translators for its operations against the Red Army on the nearby Eastern front. Then, in early March 1942, the head of a Tank Group, Ewald von Kleist, ordered the formation of three “ethnic German” cavalry units (Reiterschwadronen). These were to be used as guards in the Halbstadt area, and weapons and uniforms were provided by the Army.12 A Mennonite named Jacob Reimer, then a teenager, later recalled that the mayor of his village had called a meeting of all men of fighting age and requested volunteers. “The principle of non-resistance was forgotten,” Reimer wrote after the war, “and the men felt it their duty to assist in the struggle against the fearful oppression we had been subjected to for so long.”13

Special Commando R informed Heinrich Himmler of the Army’s intrusion into the affairs of its subsidiary, Einsatzgruppe Halbstadt, which was responsible for administering the colony. Himmler, who styled himself the Reich Commissar for the Strengthening of German Race, was eager to cement SS control in Halbstadt. He forbade the new cavalry units from being taken out of the area, emphasizing: “They are not under Army jurisdiction.”14 At Himmler’s instruction, the soldiers were placed under the jurisdiction of SS-Obergruppenführer Hans-Adolf Prützmann, who oversaw police and anti-guerilla activities across Ukraine and south Russia. While the regiment remained a standard “Self Defense” force for several months, it was reorganized within the Order Police in late 1942 and joined the Waffen-SS in early 1943, receiving new commanders and uniforms.15

Himmler broadly intended the region’s “ethnic Germans” to be involved directly in Nazi Germanization and ethnic cleansing efforts. Potential rivals were informed: “The Germans in the East are to take up arms as a totality. They are to be aids to the police.”16 Military trainers belonging to the Waffen-SS provided intensive education to the Halbstadt regiment.17 The Mennonite Jacob Reimer reported that his cavalry training consisted of technical drills, such as horse and weapons handling, as well as anti-Semitic propaganda and other ideological content. One high-level directive for training “ethnic German” cavalry soldiers for service with the Waffen-SS explained that the goal of such instruction was “to free the ethnic Germans from spiritual burdens and disappointments and to educate them into good comrades and uncompromising fighters.”18 In practice, this meant a willingness to kill unarmed victims.

The Halbstadt regiment’s exact activities require additional inquiry. The soldiers’ duties are known to have included protecting the colony from robbery, military deserters, and general unrest, as well as guarding bridges, roads, and train lines against sabotage. Members also supervised the construction of military installations, such as new barracks for themselves in Tokmak, likely using forced labor. Available sources do not indicate the extent to which the regiment may have engaged, like other “ethnic German” cavalry units, in the liquidation of Jews or Red Army prisoners outside the colony. SS task forces had already murdered 36 Jews in Halbstadt prior to the regiment’s formation. But cavalry members were expected to kill any Jews remaining in the colony or encountered elsewhere. On at least one occasion, the soldiers willingly did so.19 They may also have participated in the murder of 81 Roma.20

The regiment was certainly involved in extensive warfare against so-called partisans. These “partisans” may have included armed bands who opposed the German occupation, but records of anti-partisan campaigns conducted by the SS include murder tallies of tens of thousands of unarmed men, women, and children. The first months of the Halbstadt units’ operation coincided with the initiation of a brutal ethnic cleansing campaign in nearby Crimea, which the Nazis eventually planned to incorporate into a new German province. Hitler ordered the deportation of Russians and Ukrainians from the peninsula as well as the murder of all people considered racially or politically dangerous.21 Fueled by violence in Crimea and elsewhere in the region, southern Ukraine remained an area of anti-partisan activities until December 1942.22

Jurisdictional clashes between the SS and Nazi civil authorities erupted in September 1942 as the Reich Commissariat Ukraine expanded to include Halbstadt and surrounding areas. Erich Koch, the governor of the newly enlarged wartime province, sought control over police activities, putting him into conflict with the SS leader Hans-Adolf Prützmann.23 Koch expressed concern over the application of collective punishment to whole villages in retribution for partisan attacks. Koch and Prützmann met for a tense discussion. During the encounter, Koch tried to bend Prützmann’s troops to his authority, while Prützmann insisted that he was answerable directly to Himmler.24 Himmler, then in Italy, took Prützmann’s side in a letter to Koch, and he promised to look into the matter shortly.25 Upon return to the region, Himmler traveled with Prützmann through Crimea and southern Ukraine, including a visit to Halbstadt on October 31 and November 1, where they inspected the “ethnic German” cavalry units.26

During late 1942 and early 1943, members of the Halbstadt regiment traveled into the war zone for operations far from the colony. One unit was reportedly decimated in anti-partisan actions in the Don area.27 Others may have aided the transportation of fellow “ethnic Germans” from Donbass, Caucasus, and Kalmykia. More than 3,000 German speakers from the eastern settlements of Mariupol, Grunau, and Kharkiv had already been relocated to Halbstadt.28 The SS planned to bring thousands more from the war zone, accommodating newcomers through the expulsion of local Ukrainians.29 From January through mid-March of 1943, Einsatzgruppe Halbstadt moved nearly 10,000 “ethnic Germans.” Battle losses on the Eastern Front changed SS plans, however, and most refugees were sent on to Poland rather than settled in Ukraine. That 2,500 fled back into the war zone hints at the violence of even allegedly humanitarian actions.30

Mennonite men in Ukraine continued to be inducted into the Waffen-SS during 1943. The Eastern Front’s deteriorating state and ongoing atrocities behind German lines had fueled local opposition to the occupation, and in June, authorities once again declared southern Ukraine to be a zone of major partisan activity.31 Two months later, Himmler ordered the recruitment of 1,200 men from Halbstadt and the non-Mennonite Hegewald colony.32 In part, this reflected Himmler’s desire to keep fighting-aged “ethnic Germans” from being conscripted into the Army after its defeat at Stalingrad.33 He intended new recruits to form a regiment with a cornflower as its insignia within the SS Cavalry Division (recently expanded from the SS Cavalry Brigade), still engaged in murder to the north. By September, this division moved to southern Ukraine, where it joined the German retreat to the Dnieper River, near the largest Mennonite colonies.

The Nazi military continued its halting retreat into the Reich Commissariat Ukraine as Stalin’s Red Army pushed westward. Rather than allowing Mennonites and other alleged Aryans to fall back into Soviet hands, the SS planned to move all “ethnic Germans” west into zones of safety. In September 1943, occupiers relocated 67,000 “ethnic Germans” west of the Dnieper River. The Halbstadt cavalry regiment assisted in transferring their colony’s 28,500 residents beginning on September 12.34 Traveling by train and in wagon treks comprising between 4,000 and 8,000 people, they were initially quartered in areas around the Kronau colony (which had a large Mennonite population) in homes taken from Ukrainians. In Prützmann’s overly optimistic view, the Halbstadt Mennonites could remain there permanently.35 But the Red Army continued to advance. Between late October and early December, the treks again moved west to the Polish border, settling for several months with other refugees in the region around Kamianets-Podilskyi.

The westward trek of Ukraine’s Mennonites with the SS constituted an unmitigated stream of violence against other peoples. One Halbstadt native justified the requisitioning of homes from Ukrainians for “ethnic German” use in his memoirs: “That is a radical solution to the housing question, which truly amazes us, but it is war; life is harsh and we, too, have become harsh.”36 Cavalry member Jacob Reimer—who changed his name to the more Aryan-sounding “Eduard”—recalled how his unit combed through forests, marching between the trees in straight lines with orders to kill partisans on sight. Reimer’s regiment burned villages and shot civilians. In a letter to Himmler, Hans-Adolf Prützmann reported that the “ethnic Germans” remained in good spirits despite their itinerancy and deprivations. He assessed that they were eager to remain under German rule, and he commended the Halbstadt group for being highly cooperative.37

In March 1944, the Halbstadt refugees moved westward yet again. As Ukraine fell to the Red Army, the colony’s former residents crossed into Poland, many traveling by train from the city of Lemberg (Lviv) to Litzmannstadt (Łódź) in the Nazi wartime province of Warthegau. There, SS employees processed them as immigrants to the German Reich, sifting them through racial lists, granting citizenship, and assigning them to transit camps or to houses and farms requisitioned from Jews and Poles. The Halbstadt cavalry regiment, meanwhile, began to be disbanded piecemeal. Jacob Reimer and most of his fellow soldiers were sent to Hungary, where they joined the SS-Cavalry Division, which had been reassigned from Ukraine.38 This division fought in Transylvania before being destroyed in the siege of Budapest by early 1945.

The history of the Halbstadt cavalry regiment demonstrates the involvement of Ukraine’s Mennonites in the machinations of the Waffen-SS during the German occupation of Eastern Europe. Mennonites’ induction into this organization and their activities within it reflected the broader maneuverings of the Nazi war machine and the fate of the Eastern Front. Little of this context has survived in collective Mennonite memory. After the war, Mennonite refugees in war-torn Germany had strong incentives to deny involvement in war crimes, a process aided by church organizations. Most notably, the North America-based Mennonite Central Committee told tales of innocence while helping to transport refugees, including former Waffen-SS members, to Paraguay and Canada. Coming to terms with Mennonite participation in the Third Reich’s atrocities remains a task for the denomination.

Ben Goossen is a historian at Harvard University. He is the author of Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, available in paperback from Princeton University Press.

- On Mennonites and the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, see Benjamin Goossen, Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), 147-173; Viktor Klets, “Caught between Two Poles; Ukrainian Mennonites and the Trauma of the Second World War,” in Minority Report: Mennonite Identities in Imperial Russia and Soviet Ukraine Reconsidered, 1789-1945, ed. Leonard Friesen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 287-318; James Urry, “Mennonites in Ukraine During World War II: Thoughts and Questions,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 93, no. 1 (2019): 81-111.↩

- Wiens held the rank of SS-Obersturmführer. See his SS officer file in A3343, roll 243B, archived in Captured German and Related Records on Microfilm at the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland (hereafter cited as NARA).↩

- Günther Fieguth, “Volksdeutscher Aufbruch am Dniepr,” December 13, 1942, German Captured Documents Collection, reel 290, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.↩

- Gerhard Rempel, “Gottlob Berger and Waffen-SS Recruitment, 1939-1945,” Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift 27, no. 1 (1980): 107-122.↩

- Martin Bormann to Alfred Rosenberg, July 23, 1942, T-175, roll 194, NARA. On the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, see Wendy Lower, Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Karel Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Dearth in Ukraine under Nazi Rule (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004). ↩

- Heinrich Himmler, “Richtlinien für die Durchkämmung und Durchstreifung von Sumpfgebieten durch Reitereinheiten,” July 28, 1941, T-175, roll 109, NARA. ↩

- Jürgen Matthäus, “Operation Barbarossa and the Onset of the Holocaust, June-December 1941,” in Christopher Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 279.↩

- Heinrich Himmler to Werner Lorenz, July 11, 1941, M894, roll 11, NARA.↩

- “Zusammenstellung der erfassten Volksdeutschen im Reichskommissariat Ukraine, in Transnistrien und im Heeresgebiet,” ca. July 1943, T-175, roll 72, NARA.↩

- “Bericht des SS-Sonderkommandos der Volksdeutschen Mittelstelle über den Stand der Erfassugnsarbeiten bis zum 15.3.1942,” T-175, roll 68, NARA.↩

- Horst Hoffmeyer, “Bericht,” March 15, 1942, T-175, roll 68, NARA.↩

- Ibid.↩

- Gerhard Lohrenz, ed., The Lost Generation and Other Stories (Steinbach, MB: Derksen Printers, 1982), 50.↩

- Heinrich Himmler to Werner Lorenz, April 10, 1942, T-175, roll 68, NARA. Special Commando R also oversaw the recruitment of “ethnic Germans” for cavalry units in Romanian-occupied Transnistria. Unlike the Halbstadt regiment, however, these other units seem to have remained part of “Self Defense” formations outside Waffen-SS jurisdiction (although around a fourth of such soldiers in Transnistria were transferred to separate Waffen-SS formations in 1943, and most of those remaining were conscripted into the Waffen-SS in Poland in 1944). See Eric Steinhart, The Holocaust and the Germanization of Ukraine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 166-169. ↩

- The Halbstadt cavalry units were restructured twice while based in Ukraine. First, Himmler’s visit to the colony on October 31 and November 1, 1942, resulted in the formation being renamed the Halbstadt Ethnic German Regiment. According to a November 6 letter to the chief of the Order Police in Kiev, this occurred “in the context of the reorganization of the ethnic German Self Defense forces,” and the regiment was to be headed by an “SS leader experienced in ethnic [German] work.” Second, as reported by Hans-Adolf Prützmann on April 7, 1943, Himmler ordered that the Halbstadt regiment be transferred from the Order Police to the Waffen-SS. The SS Leadership Main Office was therefore expected to equip the soldiers. See Thomas Casagrande, Die Volksdeutsche SS-Division “Prinz Eugen”: Die Banater Schwaben und die Nationalsozialisitischen Kriegsverbrechen (Frankfurt a.M.: Campus Verlag, 2003), 327-328.↩

- SS-Obersturmbahnführer to Gottlob Berger, July 6, 1942, T-175, roll 122, NARA.↩

- “Volksdeutsche Reiter-Schwadrone,” June 5, 1942, T-175, roll 68, NARA.↩

- “Besondere Anweisungen für die weltanschauliche Erziehung,” April 5, 1943, T-175, roll 70, NARA.↩

- “Molochansk,” Yad Vashem, https://www.yadvashem.org/untoldstories/database/index.asp?cid=568; Harry Loewen, ed., Long Road to Freedom: Mennonites Escape the Land of Suffering (Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press, 2000), 110.↩

- Mikhail Tyaglyy, “Nazi Occupation Policies and the Mass Murder of the Roma in Ukraine,” in The Nazi Genocide of the Roma: Reassessment and Commemoration, ed. Anton Weiss-Wendt (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013), 128.↩

- “Aussiedlung aus der Krim,” July 12, 1942, T-175, roll 122, NARA.↩

- “Bandenlage im Gebiet des Reichskommissariats Ukraine und im Gebiet Bialystok,” December 27, 1942, T-175, roll 124, NARA. ↩

- Erich Koch to the Höheren SS- und Polizeiführer, September 10, 1942, T-175, roll 56, NARA. The transfer of the Halbstadt regiment from Order Police auspices to the Waffen-SS in early 1943 appears to have particularly irritated Koch, whose response suggests that this development was unusual within the Reich Commissariat Ukraine. In June 1943, Koch wrote to Himmler: “you yourself expressed the wish [during previous discussions], that local military commandos were not yet appropriate for ethnic Germans in the Ukraine, because they are supposed to be getting used to the standards of living of the Germans from the Reich. I have tried hard to fend off the formation of local military commandos and the conscription of ethnic Germans. I am thus all the more troubled that recruitment has occurred at your order [in Halbstadt].” See Ingeborg Fleischhauer, Das Dritte Reich und die Deutschen in der Sowjeutnion (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1983), 145.↩

- Hans-Adolf Prützmann, “Aktenvermerk über Besprechung mit Gauleiter Koch am Sonntag, den 27.9.42 in Königsberg,” T-175, roll 56, NARA.↩

- Heinrich Himmler to Erich Koch, October 9, 1942, T-175, roll 56, NARA.↩

- Heinrich Himmler, Der Dienstkalender Heinrich Himmlers 1941/42 (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 1999), 603-604.↩

- Lohrenz, ed., The Lost Generation, 58.↩

- Himmler to Lorenz, April 10, 1942; “Zusammenstellung der erfassten Volksdeutschen.” The total number of re-settlers was reportedly 3,296. ↩

- Werner Lorenz to Heinrich Himmler, January 15, 1943, M894, roll 10, NARA.↩

- Horst Hoffmeyer, “Bericht über den Abtransport der in den Einsatzgruppen Halbstadt und Nikopol sowie der Aussenstelle Kiew aufgefangenen Volksdeutschen aus dem Kauskasus, dem Donbas, der Kalmückensteppe und dem Charkower Gebiet,” ca. mid-1943, T-175, roll 72, NARA.↩

- Heinrich Himmler to Erich Koch et al., June 21, 1943, T-175, roll 140, NARA.↩

- Heinrich Himmler to Gottlob Berger, August 9, 1943, T-175, roll 70, NARA.↩

- Gottlob Berger to Heinrich Himmler, August 12, 1943, T-175, roll 70, NARA.↩

- Wilhelm Kinkelin to Gottlob Berger, September 22, 1943, T-175, roll 72, NARA.↩

- Hans-Adolf Prützmann to Heinrich Himmler, October 13, 1943, T-175, roll 72, NARA.↩

- Jakob Neufeld, Tiefenwege: Erfahrungen und Erlebnisse von Russland-Mennoniten in zwei Jahrzehnten bis 1949 (Virgil, ON: Niagra Press, 1958), 125.↩

- Hans-Adolf Prützmann to Heinrich Himmler, November 16, 1943, T-175, roll 72, NARA. An October 20, 1943, report to the SS Leadership Main Office commented on the Halbstadt regiment: “In addition to fanatical hate of the Russians, the men demonstrate an excellent ability to move through the terrain. With regard to training, they are well educated and handle weapons well.” See Casagrande, Die Volksdeutsche SS-Division, 328.↩

- Lohrenz, ed., The Lost Generation, 65-70. Research by the former Waffen-SS member and chronicler Wolfgang Vopersal suggests that by 1944, the Halbstadt regiment (then reportedly called the “1st Ethnic German Cavalry Regiment of the Waffen-SS”) totaled nearly 1,000 members. Vopersal’s findings provide further details about the regiment’s postings, leadership, and activities from March 1942 to October 1944. However, much of Vopersal’s account is based on information acquired after the war; this source is thus not fully reliable and must be used with caution. See “Volksdeutsches Reiter-Regiment der Waffen-SS,” N 756/151a, and “Fotografie von Angehörigen des 1. Volksdeutschen Reiter-Regimentes,” N 756/256a, Bd. 1, Bundesarchiv Abteilung Militärarchiv, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany.↩

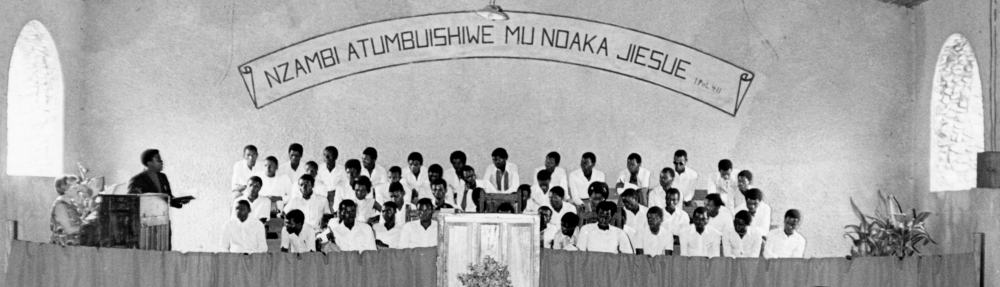

The first photograph has nothing to do with the Waffen-SS and nothing to do with Halbstadt. It is a group of young men from the Chortitza Colony in the summer of 1943. See my description of this phot in the recent edition of Roots and Branches.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Peter – thanks for the tip; I wondered about the uniforms. The photo must be mislabeled in ‘Long Road to Freedom.’ Can you send me your article so I can update the caption appropriately?

LikeLiked by 1 person

i was born in Halbstadt krs/Tokmak, and am trying to find some information on my Dad Emil Arnholz. I live in Lacombe,Alberta, Canada, thank you

LikeLike

I just went into this site again, but have not heard from anyone to give me some information. on tracing my Dad, I do not know or have any information on him. I was 9 when he died. he married my mom. Meta Heilemann/

LikeLike

Hi Peter,

The men in the photo may not be from Halbstadt, but the last two guys in the first row have the Waffen SS eagle on their tunic.

LikeLike