This post includes descriptions of sexual violence.

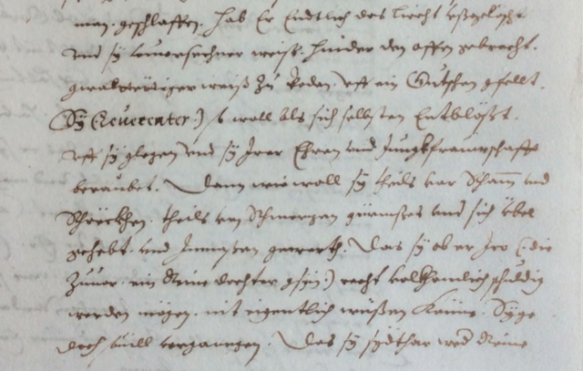

“An excerpt from the Zurich marriage court scribe’s transcription of Verena Tanner’s testimony, presented on October 9, 1630. StAZH, E I 7.5, #95.”

Verena Tanner and Anna Nägeli met Jakob Zehnder during separate visits to his home in early 1630. Both women were active in Anabaptist communities in the territory governed by the city republic of Zurich, Nägeli residing near the town of Hirzel where the family of Hans Landis, the last Swiss Anabaptist to be killed by Zurich’s city council, had a farm. They had traveled for some distance around or across Lake Zurich to Zehnder’s home in the settlement of Waltenstein, near Winterthur, as patients seeking medical treatment for illness.

Zehnder, like a significant number of fellow Swiss Anabaptist doctors, barber surgeons, and midwives, was a respected medical practitioner, who viewed the practice of medicine as a “special burden and gift of God,” a means to live out a divine call to service.1 Zehnder’s reputation, apparently well-established among local Anabaptists, surpassed the boundaries of his nonconformist religious community. The authorities’ investigation into his healing practices revealed nothing but dedicated and principled competence. In 1634, for example, the local Reformed minister testified that,

[o]n different occasions, [he] had seen Zehnder linked with very evil harm, but [Zehnder] had used nothing other than appropriate natural remedies, and he generally admonishes his patients earnestly [that] they should fervently ask and call on the loving God [that] he might wish to make the medicine successful, so that it might function and they might return to their previous health, for without God’s blessing, the external remedy is futile and for nothing. Subsequently, they inspected his printed and written books, herbs, spices, oils, etc., which were great in number, but found no spells, crucifix, characters, or any other similar superstitious things and [Zehnder] had vigorously asserted from his heart that he always [held that] all consecrations, witchcraft, dark magic, etc., things which were highly forbidden in God’s word, were an enemy, and indicated further [that] it was indeed his custom that he administers all remedies in the name of God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. If he failed in this or engaged in idolatry, it was an unconscious sin of his, for he attributes no power to words, but all effects to the love of God. If one asks if he avoids these forbidden arts in localities in Your Graces’ possession, in St. Gall, in the Netherlands, etc., where he sends remedies at his own cost, nothing of the kind is found.[^2]

Yet, contrary to the pastor’s claims, the way that Zehnder practiced medicine was not benign, at least not for women. In October 1630, the doctor found himself jailed in the Wellenberg tower by order of Zurich’s council, on the evidence of testimony provided to the city’s marriage court by Nägeli and Tanner.2 They alleged that Zehnder had sexually harassed and assaulted them, respectively, in his house. Nägeli reported that Zehnder had taken advantage of his proximity to her as he applied a remedy to her diseased finger in order to pressure her to marry him. Initially attracted by this proposal because of Zehnder’s standing, means, and her own desire to be married, Nägeli accepted a gift from him. However, she soon became suspicious of Zehnder. On numerous occasions, he tried to convince her to sleep with him “as if she were his wife,” even though she had not exchanged vows with him. She verbally repelled him, accusing him of being afflicted with the vice of lust. Zehnder responded by dismissing these accusations as “worldly” slander, insisting that God protected his people from the work of the devil. Nägeli was unmoved, eventually returning the money Zehnder had given her after hearing that he had begun a sexual relationship with a woman in a nearby village and engaged in other abusive behavior.

The details of Verena Tanner’s earlier interaction with Zehnder shed light on what had frightened Nägeli. One evening a few months before, in the doctor’s home, Zehnder had subjected Tanner, who was suffering from a “painful illness,” to similar appeals to marry him. He told her that God had informed him directly that she had been sent to him as a spouse and twice spoke a marital vow aloud, which Tanner did not reciprocate. Later in the evening, Zehnder extinguished the light, approached Tanner uninvited, threw her on a bed, and raped her. She experienced physical and psychological pain, motivated in part by her uncertainty over whether Zehnder would fulfill his marriage vow. In the morning, Zehnder forced Tanner into further sex acts, which he now claimed had medicinal benefits, and insisted that she remain silent about what had happened. When Tanner returned to Zehnder’s home three weeks later, he attempted to justify his actions by insisting that the two were now married and that she held high esteem among God’s people. This manipulation did not convince Tanner to pursue a relationship with the doctor, who redirected his attention towards Nägeli.

Zehnder appears to have avoided serious sanctions for these offenses. As a result of his identity as an Anabaptist, Zehnder’s activities were subject to intense scrutiny by Zurich’s government over the course of his adult life. The documentary evidence that resulted suggests that the doctor had a track record of abusive behavior towards women. In 1618, for example, a case against Zehnder presented to the marriage court after the death of his first wife featured accusations by a female patient against the doctor quite similar to those presented by Nägeli. Yet, when Zurich’s authorities punished Zehnder—and they did so on a number of occasions, usually through fines and property confiscation that threatened to leave him and his family in ruin—it was on account of his withdrawal from the common civic and religious life of the Reformed parish, not his sexual crimes. Even then, Zehnder was often protected from the consequences of his religious nonconformity by local officials and neighbors who valued his medical skills. In the case described here, Zehnder accepted the content of Tanner’s and Nägeli’s accusations. Yet, although the terms of the punishment meted out against him are not extant, we know he was free again soon thereafter.

The reaction of the region’s Anabaptist community is more difficult to ascertain. Nägeli reported that, after initially encouraging her to show interest in Zehnder’s proposal, the “brethren” had counseled her against betrothal. Anabaptist leaders in the southwest of Zurich’s territory must have harbored suspicions about Zehnder despite the geographic distance that separated them from him. Nevertheless, circumstantial evidence suggests that he maintained his place among the community’s membership. For example, he kept in close communication with a regional Anabaptist leader into the early 1640s. Various factors may have allowed this. Firstly, the exigencies of survival in a hostile social and political environment meant that Anabaptists were forced to rely on the scarce human resources (such as medical practitioners) available to them in networks of affinity. Secondly, the sparseness of the Anabaptist population in the area where the doctor lived suggests that the communal structures within which discipline might have been imposed on Zehnder were weak or absent. Finally, imbalances of power within the community based on the involved parties’ gender and professional status likely affected processes of discipline among Anabaptists, as they did in so many contemporary cases adjudicated by the city’s secular court.3 Whatever the reasons, local Anabaptists appear to have failed to ban Zehnder from their midst, as they did with other sexual offenders connected to their communities.4

As I write, tens of thousands of women are sharing stories online of their own experiences of sexual harassment and assault under the #metoo hashtag. For a long time, but especially in the past few years, women have revealed the extent of trauma wrought by sexual violence perpetrated by men within the church and in society more broadly. So, perhaps surprise will not accompany feelings of sadness and anger provoked by this account of what Jakob Zehnder did to Verena Tanner and Anna Nägeli and his avoidance of meaningful sanctions. Still, since the deeper Anabaptist past often serves as a well for ideas and stories that shape contemporary Anabaptist traditions, today it seems fitting to lift this story out for consideration. Two Anabaptist women, victims of a man who exercised authority within their religious community, courageously took the opportunity provided to them by a secular court to denounce their perpetrator and defend their sexual integrity.5 The content of the account narrated here relies largely on the details they decided to share, the framing they selected to recount their experiences. As a result, we know that it happened to them too.

- For more on this healing and medical culture among Swiss Anabaptists, see Hanspeter Jecker, “Im Spannungsfeld von Separation, Partizipation und Kooperation: Wie täuferische Wundärzte, Hebammen und Arzneyer das ‘Wohl der Stadt’ suchten,” Mennonitica Helvetica 39 (2016): 21-33. ↩

- The following account is based largely on Nägeli’s and Tanner’s testimonies, which are recorded in Staatsarchiv Zürich (StAZH), E I 7.5, #95. ↩

- For more on the way gender shaped prosecutions of sexual crime in Zurich, and early modern Europe more generally, see Francisca Loetz, A New Approach to the History of Violence: ‘Sexual Assault’ and ‘Sexual Abuse’ in Europe, 1500-1800, trans. Rosemary Selle (Leiden: Brill, 2015), especially 25-160. ↩

- For more on seventeenth-century Swiss Anabaptist practices of communal discipline, especially in cases of sexual offenses, see my “‘Ihr hand dergleichen Leuht auch under Euch’: Gemeindedisziplin unter Zürcher Täufern im siebzehnten Jahrhundert,” Mennonitica Helvetica 39 (2016): 34-46. ↩

- In an early modern European context, a single woman’s sexual integrity was a precondition for full participation in society, impacting her marriage prospects and family’s social standing. Tanner did later marry, as documented in records from 1640 detailing the confiscation of her and her husband Uli Öttiker’s property by Zurich’s authorities. StAZH F III 36b, 20. ↩