Since 2013, seven researchers have been investigating Mennonite agricultural practice in farming communities around the globe as part of Royden Loewen’s “7 Points on Earth Project.” We first met in Amsterdam in December of that year to discuss the logistics of conducting oral histories in small farming communities and to introduce one another to our research sites. These extended from regions traditionally associated with the Mennonite faith and farming, including nearby Friesland, the U.S. and Canadian prairies, and Russia, to less well known Mennonite communities in Bolivia, Indonesia, and Zimbabwe. Leaving Amsterdam, we scattered to our seven points. I spent five months in mid-2014 and one month in the spring of 2015 in the Department of Santa Cruz in the tropical eastern lowlands of Bolivia traveling muddy colony roads by bicycle as I conducted interviews with Mennonites farmers.

Street Scene in Riva Palacio

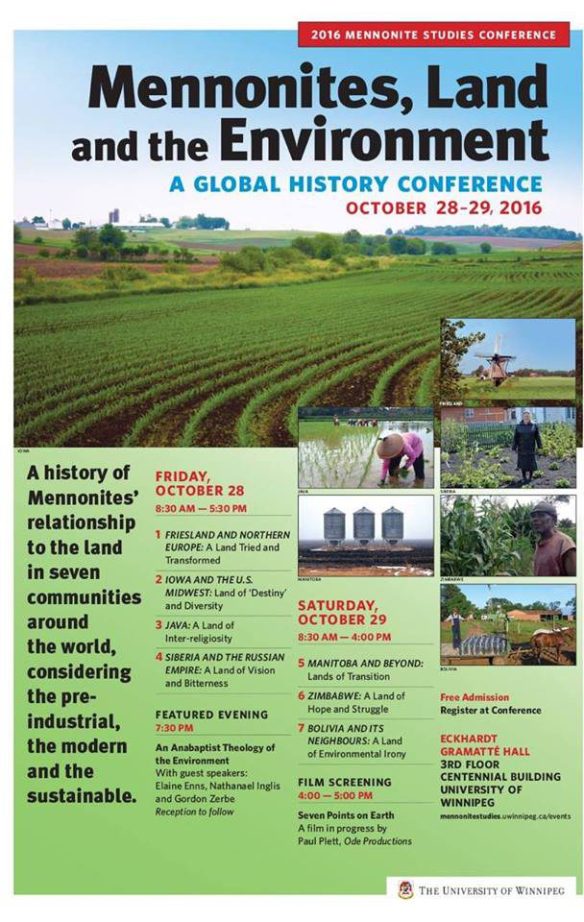

On October 28-29 we will be reconvening in Winnipeg to discuss our findings as part of a public conference on “Mennonites, Land, and the Environment.” For those that may not be able to attend the conference I offer here a brief portrait of Mennonite history and farming in one of those Seven Points on Earth.

While Mennonites migrated to Bolivia from Canada, Paraguay and Belize, the majority were horse-and-buggy “Old Colony” Mennonites from Northern Mexico who began to settle in the department of Santa Cruz in 1967. Their migration offers observers a compelling paradox. On the one hand, they were part of a religious pilgrimage to maintain traditional ways they saw as under threat in modernizing North American Mennonite colonies. On the other hand, they successfully presented themselves to the Bolivian government as modern farmers, capable of transforming the densely forested landscape of lowland Bolivia into a series of productive agricultural colonies.

As Mexican Mennonites approach their fifty year anniversary in Bolivia and the country’s Mennonite population nears 100,000, that duality remains as apparent as ever. Old Colonists, most of whom continue to use horse-and-buggies on the roads and lumbering steel-wheeled tractors in the fields, might appear to live traditional, isolated lives. Yet they are also key producers for a regional economy that has emerged as one of Bolivia’s largest and most dynamic. They farm over a third of Bolivia’s soybeans, the country’s star agricultural crop, with a harvest in 2015 of over two million metric tons and an export value of one billion U.S. dollars. As soy farmers they are at the center of a broad swath of South America – including portions of Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina – that now produces the majority of the world’s soy.

A field of soybeans in Riva Palacio colony

Even as Mennonites generate this high-value, export-oriented commodity that depends on intense mechanization, nearly every farmer in Riva Palacio, Bolivia’s largest Mennonite colony and my primary research site, rises early in the morning to milk their herd of dairy cattle by hand. Buckets clang and wooden stools are set down as the entire family – men, women and children – take part in this laborious daily activity which will be repeated again in the early evening. By the time the last cow is milked the sun is usually rising and one member of the family pushes a cart laden with brimming metal jugs out to the corner to wait for the milk-men that travel through the village by horse cart.

Milk awaiting pickup at the entrance to a Mennonite homestead

The practice is both intimate and, for scholars of Old Colony Mennonites, historical in nature. While Mexican Mennonites had never produced soybeans before arriving in Bolivia, they successfully transplanted a dairy industry from Chihuahua to Santa Cruz. Farmer Enrique Siemens still remembers the first year in Bolivia when as a young boy he drank powdered milk because there were no dairy cattle to be had in local markets. In 1969, his father traveled with a friend to neighboring Paraguay to bring back the colony’s first Holstein cattle – a journey of forty days. “When I arrived back at home [from school] the cow was already there,” he exclaims, “and oh[!] after that we were happy, then we had milk.”

Enrique Siemens sits in his buggy during an interview with the author

What to make of this dual – and diametrically opposed – agrarian economy? The respective meanings attached to cash cropping and dairy farming in Bolivian Mennonite colonies form a central aspect of my research. Linked with nourishment and happiness in Siemens’ memories, daily family milk production seems to stand in opposition to the capital-intensive cash-cropping of export commodities like soybeans. Indeed, even the income earned from the two activities is treated in different ways. Harvest money might be invested in new land and machinery to expand one’s operations. Milk money, by contrast, provides regular access to goods on credit at the colony’s small stores – particularly critical in drought years when the harvest might fail altogether.

An example of this form of accounting can be seen below for David Unger, a farmer in a nearby Paraguayan Mennonite colony. For each two week period, daily milk production (morning and evening) is divided into that which was of a quality to be sold as milk and that which, due to its higher bacterial content, is only suitable for making cheese. From those two balances Unger’s purchases at the colony store over the same period are deducted and the balance is passed on to him.

Jakob Unger’s biweekly balance sheet, Canadiense Colony

Yet, the intimate snapshot of daily milking can be deceptive. Dairy, a fringe industry when Mennonites arrived in Santa Cruz, is now, like soybeans, big business. It is no coincidence that both the milk and the soy produced in Mennonite colonies find their way to Santa Cruz’s sprawling industrial park. There, across the highway from one another sit IOL Aceite, the largest oil-seed production plant in Bolivia and PIL Andina, the country’s sole major dairy distributor.

IOL has been encouraging Mennonite soy production with seed and credit since the mid-seventies. In contrast, PIL only began to install collection centers on the edge of most major colonies in 2000. This has led to changes for the company and for colonists. Mennonites once processed all of their milk as cheese to be sold in the streets of Santa Cruz. Farmer Cornelio Peters remembers that “before, the milk was worthless…there was too much [cheese] with all the Mennonites here in Bolivia.”

The arrangement between PIL and the Mennonites appears mutually beneficial. The presence of the company has meant price stability for Mennonites, while the increased milk supply has also enabled PIL to double its production. Riva Palacio alone produces approximately 100,000 liters of milk a day. On a tour of the installation in 2014, the operations manager explained that approximately four-fifths of their daily capacity of 500,000 liters came from Santa Cruz’s Mennonite colonies.

As Mennonites moved from independent producers of cheese – which everyone in Bolivia knows as “queso menonita” – to suppliers of a primary input for a large corporation, the potential for tension also exists.

Mennonite cheese (“queso menonita”) for sale in a La Paz grocery store

When I returned to Santa Cruz in 2015 I found Riva Palacio colony up-in-arms. While PIL had been paying 2 Bolivianos and 30 centavos per liter for their milk, they had recently discovered that the minimum price to be paid to producers – by national decree – was three Bolivianos and fifty centavos. A hastily formed “Mennonite Federation of Milk Producers” – representing 3000 families – was calling emergency cross-colony meetings, contracting lawyers, and petitioning PIL, the president of Bolivia, Congress and the Senate to demand “a fair price for Mennonite milk.”

Letter from Ombudsman to PIL administration on behalf of Mennonites posted alongside a call for an Extraordinary Meeting of the Mennonite Federation of Milk Producers in the Mennonite Market in Santa Cruz de la Sierra

The above sketches of Mennonite soy and dairy demonstrate not simply the importance of different production strategies to the survival of colonists but the ways in which that daily production – on the fields and in the milking barns – is interwoven with regional and global markets. Popular and scholarly approaches to Old Colony Mennonites have tended to accept the idea that these are “a people apart.” Steel wheels and milk jugs at the end of the road tend to confirm such impressions. Yet whether they are quietly acting as the largest producers of Bolivian soybeans or actively demanding a “fair price for Mennonite milk,” Old Colonists are embedded in broader economic structures. This is a conversation – about Mennonite history and place-making – that we look forward to continuing at the University of Winnipeg next month. Hope to see you there!

© Benjamin Nobbs-Thiessen 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material (including images) without express and written permission from this author is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Benjamin Nobbs-Thiessen with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.