“You wouldn’t think corn is fascinating, but it is.” And with this comment, so launched the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society’s final “Midstate Memories” segment.

In 2014, Good Day PA, a program on WHTM/ABC27 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, began “Midstate Memories” as a repeating segment of its live show to educate viewers about history in central Pennsylvania and efforts to preserve that history. The vision was for brief spots—two and a half to three minutes of live television—that covered “one specific event (or anniversary of an event), an industry, a building, a natural disaster, a special visit of a prominent person, etc,” that also included strong visuals, whether photos, artifacts, or film footage. A caveat was that each segment was not to be promoting an upcoming event by the presenting organization, but instead “the essence of the segment [should] be a mini history lesson.” For 2014 and 2015, the segment ran every Tuesday sometime between 12:30 and 1 p.m., depending on the other portions of the show. In 2016, “Midstate Memories” aired the second and fourth Tuesdays of each month. In the first year, there were eleven participants, increasing to twelve in the second year, and thirteen for 2016.1 Each participating organization provided a scripted interview for its respective segments, which was then filmed live.

I became involved in my role as Director of Communications for the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society (LMHS), which includes the 1719 Hans Herr House & Museum. Over three years, we organized eleven segments:2 four each for 2014 and 2015, three for 2016. There topics were as follows:

- Mennonite hymnody

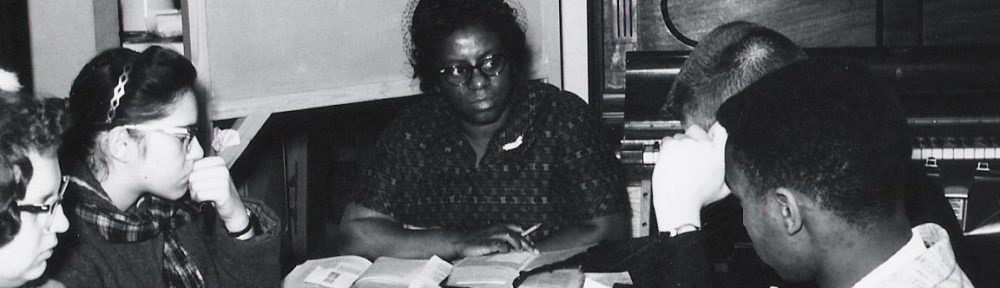

- Hispanic Mennonites in Lancaster, Pa.

- Mennonite films

- Travel and Mennonite emigration/immigration

- Mennonite connections between Lancaster and the rest of the world

- DNA and Genealogy

- West Willow, Pa.

- Native Americans in Central Pa.

- Collecting historical photographs

- Grain Harvesting

- The history of corn

My general approach was to choose an upcoming event, and then do a segment on a topic related to what would be covered so that I could promote LMHS events while still living into the purpose of Midstate Memories. For example, the 1719 Hans Herr House & Museum, as well as the upcoming Christmas Candlelight Tours, focus on the role of corn in Native American society and how European immigrants interacted with it, and so on November 22, we focused the segment on corn. The presentation on connections between Lancaster and the broader world integrated the preparatory work the Society did leading up to Mennonite World Conference in Harrisburg, Pa., specifically the 2015 Annual Music Night which focused on the music of Anabaptist-associated immigrants to Lancaster (hymns, yes, but also norteño and more).

I was only in front of the camera for one spot. For the others, I worked with other LMHS staff persons or volunteers who were more connected with the topic, and had them present. When the segment was on Hispanic Mennonites, I turned to Rolando Santiago, our director, because this is part of his story. When the topic was Native Americans, I looked to Ruth Py, a volunteer educator for the Lancaster Longhouse at the 1719 Hans Herr House & Museum, because it is her story.

It is hard to quantify how successful these segments were. I have no hard data, only anecdotal evidence. As a marketing endeavor, there was no detectable impact on event attendance, and limited increases in website visitation and social media engagement. In terms of educating midstate residents about history, I can but wonder. It was only in the final year that I felt I had an effective approach—mostly on account of trying to accomplish too much in previous years during the very limited time slot. However, after each spot, I left feeling as if each segment’s core message had been communicated adequately, even if not in the depth I had hoped. Appearing on Good Day PA also presented the opportunity to reach out to a much larger audience in a very different space than usual for the Society, and making history known and visible in that way is valuable.

- Email Correspondence between the author and Good Day PA staff between 2014 and 2016. ↩

- See some of those here: http://abc27.com/?s=Lancaster+Mennonite+Historical+Society ↩

In 1920 Mennonites from different ethnic and church backgrounds formed Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) to collaboratively respond to the famine ravaging Mennonite communities in the Soviet Union (Ukraine). Over the ensuing century, MCC has grown to embrace disaster relief, development, and peacebuilding in over 60 countries around the world. MCC has been one of the most influential Mennonite organizations of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It has operated as a mechanism for cooperation among a wide variety of Mennonite groups, including Brethren in Christ and Amish, constructing a broad inter-Mennonite, Anabaptist identity. Yet it has also brought Mennonites into global ecumenical and interfaith partnerships.

In 1920 Mennonites from different ethnic and church backgrounds formed Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) to collaboratively respond to the famine ravaging Mennonite communities in the Soviet Union (Ukraine). Over the ensuing century, MCC has grown to embrace disaster relief, development, and peacebuilding in over 60 countries around the world. MCC has been one of the most influential Mennonite organizations of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It has operated as a mechanism for cooperation among a wide variety of Mennonite groups, including Brethren in Christ and Amish, constructing a broad inter-Mennonite, Anabaptist identity. Yet it has also brought Mennonites into global ecumenical and interfaith partnerships. “Anabaptist Historians: Bringing the Anabaptist Past into a Digital Century” is a collaborative blog gathering scholars of Anabaptist history to share their research and engage on critical issues in contemporary Anabaptist life. But what is Anabaptist history? Part of the trouble is that the word “anabaptist” has many overlapping meanings, as does “Mennonite.” In this blog, each contributor will have his or her own understanding of what “Anabaptist” and “Anabaptist history” means.

“Anabaptist Historians: Bringing the Anabaptist Past into a Digital Century” is a collaborative blog gathering scholars of Anabaptist history to share their research and engage on critical issues in contemporary Anabaptist life. But what is Anabaptist history? Part of the trouble is that the word “anabaptist” has many overlapping meanings, as does “Mennonite.” In this blog, each contributor will have his or her own understanding of what “Anabaptist” and “Anabaptist history” means.