Abigail Carl-Klassen, Anna Wall, and Veronica Enns

50 years after their arrival from Prussia in the 1870s, 7,000 Altkolonier (Old Colony) Mennonites left Manitoba and Saskatchewan to form new, more conservative colonies in northern Mexico, due to conflicts with the Canadian government concerning secularization and compulsory English language instruction mandates for colony schools. The Mexican government promised Old Colony communities educational autonomy and exemptions from military service in exchange for occupying and developing remote, yet contested, territory in the wake of the Mexican Revolution. The first colonies in the states of Chihuahua and Durango were established in 1922 and 1924 respectively and grew quickly as a result of high birthrates and subsequent migrations. Today there are more than 100,000 Mennonites living in Mexico, primarily in Chihuahua and Durango, but also in more recently settled colonies in Zacatecas, San Luis Potosi, Quintana Roo, Tamaulipas and Campeche. Descendants of this migration have also participated in subsequent migrations and have formed colonies in Belize, Bolivia, Paraguay, and most recently Peru and Colombia.

In the early days of the Mexican colonies, residents were isolated geographically and socially from larger Mexican society; however, over time, modernization of agriculture, industry, and transportation has increased commercial contact with surrounding Mexican communities and social and commercial contact with Mennonite colonies throughout the Americas. Today it is not uncommon for colonies with modern dress, cars, Internet, and schools accredited by the Mexican education system to exist within close proximity of colonies with much more strict and traditional regulations concerning dress, education, and technology.

Editor’s Note: While Anabaptist Historians generally focuses on historical research, in the interdisciplinary spirit of “Crossing the Line”, we are broadening our scope during this series to include a wide variety of Anabaptist studies.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, Mennonites in Mexico have become increasingly mobile and transnational. In the 1970s, several thousand Old Colony Mennonites from Mexico, many of whom still retained Canadian citizenship, began migrating to Ontario while others established a new colony in Seminole, Texas. While many formed migrant worker circuits residing in Canada and/or the United States for half the year to perform agricultural work and returning to Mexico for the other half, others settled permanently. These migrations continue to the present day and impact the social and cultural landscape of colonies in all three countries.

“Art, Migration, and (Home)making: Mennonite Women, Mexico and ‘the World’” was a panel at Eastern Mennonite University’s Crossing the Line: Anabaptist Women Encounter Borders and Boundaries conference that sought to explore the personal side of this complex network of migrations and identities through the presentation of poetry, creative non-fiction and visual art.

Abigail Carl-Klassen, who grew up in Seminole, Texas, read poetry based on ethnographic research and oral history interviews that she conducted in Seminole, Texas and Chihuahua, Mexico. The poems “Freizeit” and “Self-Portraits with the Flower Women” explored the multi-faceted encounters that Old Colony women had with personal, community, and geographic borders from the 1940s to the present day. Her work can be found at https://abigailcarlklassen.wordpress.com/

Reflecting on the panel and her conference experiences Abigail noted,

When I started writing I didn’t know there was such a thing as Mennonite literature or scholarship. I just knew that I needed to tell the compelling stories of the people around me. While I was working on my thesis, a collection of poems based on the experiences of friends and family in Old Colony communities in Mexico, I was introduced to a thriving community that welcomed me into the fold. When I slip the work of Di Brandt, Sarah Klassen, or Julia Kasdorf into the hands of women I grew up with or connect someone from my community with Rhubarb or the work of Royden Lowen it’s like experiencing that joy of discovery all over again.

I organized this panel because I feel it is important that Mennonite women from colonies in Mexico be able to tell their own stories and have a space to showcase their creative work. Though Anna, Veronica and I only knew each other through social media before the conference, I felt like we had an instant connection and would be good friends. I was overwhelmed by the positive response that our panel received and am excited about new opportunities for collaboration and about the ways these connections will open up ways for women of Old Colony origin to share their experiences and creative work whether they are living in Mexico, the U.S., Canada, or elsewhere in the Americas.

Anna Wall, who blogs at http://www.mennopolitan.com/ about her experiences growing up in a conservative colony in Durango, Mexico, read a creative non-fiction piece from her blog that explored her struggles leaving the colony and as a new immigrant in Canada. With humor and seriousness she talked about learning to read and write, earning her high school diploma, finding her identity and her current job as a community health worker and Plautdietsch interpreter in Ontario.

Anna shared her experiences as an attendee and presenter saying,

At the age of 16, I crossed a pivotal boundary, and two borders when I left my colony that is tucked away, hidden far in the mountains of Durango, Mexico. I left everything I had ever known and came to Canada. I was illiterate and didn’t speak English. I faced many barriers as I began my journey of learning how to fit into a whole new world that I had never been part of before.

At the age of 19, I began attending an adult learning center in St. Thomas Ontario. At that point, I had only ever written my name a handful of times. Even just simply holding a pen in my hand was awkward. I was ashamed of my literary incompetence and felt like I was going to kindergarten. Reading and writing have become my obsession ever since.

Three years ago, I started a blog www.mennopolitan.com I post stories of my lived experience growing up as an Old Colony Mennonite. Going to kindergarten in Canada as an adult, being torn between two worlds and finding my place in it.

When I received and email from Abigail Carl-Klassen telling me that she had been following my blog for a while and invited me to participate in a panel that would showcase creative work by and about women from Mennonite communities in Mexico. Discussing transnational identities and issues. I said YES! Before I finished reading the email.

Within minutes of meeting both Abigail and Veronica, I immediately connected with both of them. The experience was soulful.

It was surreal. Not only being in the presence of such scholars I had only read about, but discussing an art piece with Canadian History Professor Royden Loewen in Plautdietsch and sharing my dream of publishing a memoir with author Saloma Miller Furlong, while comparing notes on similar experiences and how we are still struggling with how to dress our bodies after leaving our communities. I left the conference with an abundance of knowledge and new relationships. The experience has inspired me to no end. Thank you for opening the door!

Veronica Enns, a visual artist, and creative director at Cabañas Las Bellotas in Chihuahua, whose work can be found at http://www.veronicaenns.com/ shared her experiences growing up in a conservative colony in Chihuahua, her immigration to Canada as a young woman, and how studying and creating art allowed her to process and heal from past trauma. She also discussed what ultimately motivated her to move from Vancouver back to Mexico, close to the colony where she was raised. Currently, she runs a ceramics studio, gives community arts workshops, has exhibitions in Mexican galleries and works on collaborative projects with Mexican artists. Most recently, her work was showcased at the Festival of Three Cultures which seeks to celebrate and bring together the indigenous Tarahumara, Mexican, and Mennonite communities in the Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua region.

She spoke excitedly about her experiences at the conference saying,

Growing up [in a conservative colony in Mexico], I didn’t think that Mennonite and education went together. I never imagined that a conference like this was possible—that people went to university to learn about Mennonites and that our life in the colony was the subject of academic study or that I would be a part of that by presenting here. When I left the colony I thought I was done being Mennonite, but over the years I’ve been brought back to my roots in new ways.

Several years ago, a friend of mine gave one of my paintings to Elsie K. Neufeld, a writer, photographer and storyteller of Mennonite origin who lives in Vancouver, Canada. Elsie was curious to find out more about the artist, as she linked my last name to be Mennonite. Thanks to social media we connected a few months after I moved from Vancouver back to my roots in Chihuahua, Mexico. Elsie met Abby Carl Klassen on a writing conference in Fresno California in 2015 and shared some details about my art and experiences. This connected Abby to me and the ball got rolling.

I trusted that my presentation would be embraced at this conference. Although not knowing anyone in person and having compiled a bunch of personal stories made me very nervous; however, a few hours after arriving on the EMU campus, I felt overwhelmed with the warmth in hospitality. I was impressed with all the highly educated personalities and how humbly they shared their own personal stories as we all had walked common grounds as woman who often encounter similar boundaries. Academics and faith had never been used together before in my educational and cultural experience. I had found my tribe.

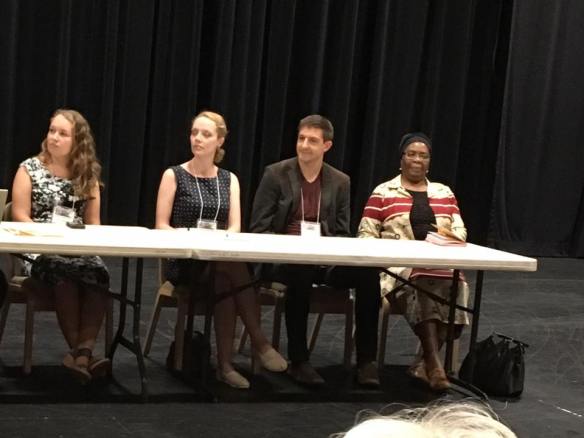

Barbara Nkala’s talk on “Unsung Heroines” of the BICC Zimbabwe was delivered with clarity and authority. Based on her own and her sister Doris Dube’s extensive work of collecting stories of women of the BICC Zimbabwe, Barbara’s joyful spirit came through, as well as her well-honed teacher’s expertise. A longtime secondary school teacher at the BICC’s Matopo Secondary School, she is now a publisher of Christian and Ndebele literature and serves as the southern Africa regional representative for MWC. I had not seen Doris and Barbara since 1999; our reunion at Crossing the Line was poignant and joyful. See the photo of the three of us standing before EMU seminary’s gorgeous stained glass window. Note also the photo of the conference’s wrap-up panel, which includes Barbara Nkala seated at the far right.

Barbara Nkala’s talk on “Unsung Heroines” of the BICC Zimbabwe was delivered with clarity and authority. Based on her own and her sister Doris Dube’s extensive work of collecting stories of women of the BICC Zimbabwe, Barbara’s joyful spirit came through, as well as her well-honed teacher’s expertise. A longtime secondary school teacher at the BICC’s Matopo Secondary School, she is now a publisher of Christian and Ndebele literature and serves as the southern Africa regional representative for MWC. I had not seen Doris and Barbara since 1999; our reunion at Crossing the Line was poignant and joyful. See the photo of the three of us standing before EMU seminary’s gorgeous stained glass window. Note also the photo of the conference’s wrap-up panel, which includes Barbara Nkala seated at the far right. I may well have been one of the only (if not the only) participants in the conference who is not a member of an Anabaptist-derived church. I felt welcome; I became more deeply acquainted with the Anabaptist tradition, and came to admire and appreciate my Anabaptist fellows in Christ and in scholarship all the more. Thank you to the conference planners who accepted my paper proposal, allowing me to partake of these riches.

I may well have been one of the only (if not the only) participants in the conference who is not a member of an Anabaptist-derived church. I felt welcome; I became more deeply acquainted with the Anabaptist tradition, and came to admire and appreciate my Anabaptist fellows in Christ and in scholarship all the more. Thank you to the conference planners who accepted my paper proposal, allowing me to partake of these riches.

Artists are in the habit of crossing lines. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp caused an uproar by submitting to an exhibition a mass-produced urinal that he had signed, titled,

Artists are in the habit of crossing lines. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp caused an uproar by submitting to an exhibition a mass-produced urinal that he had signed, titled, Other artists purposefully cross borders of material. Historically, the highly regarded “fine arts” materials of painting and sculpture have far outweighed the importance of craft traditions such as needlework. However, one important legacy of the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s has been the revaluation of media long denigrated as “women’s work.” Karen Reimer employs methods of embroidery and appliqué not only to bring feminized craft traditions into a high art context but also as a means by which to question the value of certain kinds of labor and notions of originality. Reimer intentionally copies her texts from other contexts as a way to destabilize definitions of creativity and innovation. As she writes, “Generally speaking, in the art world copies are of less value than originals. However, when I copy by embroidering, the value of the copy is increased because of the added elements of labor, handicraft, and singularity–traditional sources of value. The copy is now an ‘original’ as well as a copy.”

Other artists purposefully cross borders of material. Historically, the highly regarded “fine arts” materials of painting and sculpture have far outweighed the importance of craft traditions such as needlework. However, one important legacy of the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s has been the revaluation of media long denigrated as “women’s work.” Karen Reimer employs methods of embroidery and appliqué not only to bring feminized craft traditions into a high art context but also as a means by which to question the value of certain kinds of labor and notions of originality. Reimer intentionally copies her texts from other contexts as a way to destabilize definitions of creativity and innovation. As she writes, “Generally speaking, in the art world copies are of less value than originals. However, when I copy by embroidering, the value of the copy is increased because of the added elements of labor, handicraft, and singularity–traditional sources of value. The copy is now an ‘original’ as well as a copy.” Some artists cross lines as a political gesture, seeing their methods as a way to issue public statements, either subtle or explicit. In

Some artists cross lines as a political gesture, seeing their methods as a way to issue public statements, either subtle or explicit. In