Richard, first I’d like to congratulate you! The publication of Menno’s Descendants in Quebec has been a long time in the making!

Could you speak a bit about your background? You grew up in Quebec, in the home of a United Church of Canada minister and have worked as an ordained United Church minister, pastoring a joint Anglican and United Church parish in Northern Quebec. You have also trained at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary and have been a member of both Mennonite Church Eastern Canada (Mennonite Church Canada) and are now with the Mennonite Brethren. In all of this you have told me that you are more comfortable worshiping on the French side. And your scholarly work has been primarily on French Protestants in Quebec. Can you talk about how your background brought you to the book?

It sounds a bit like I was a grasshopper, jumping all over the place. That works out well for church history, but not so much for a stable church member. I’ve always been interested in Quebec. I’ve lived here for most of my life, now. I met Robert Witmer, a Mennonite missionary formerly to France, when he came to Rouyn-Noranda, where I was serving as pastor in a joint ministry of the United Church of Canada and the Anglican Diocese of northern Quebec. He started a French Mennonite church in our building. We often spoke and when I asked him what he would do in various situations, I liked what he said. I left and went to Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries to see if I could fit into the Mennonites, and I was attracted at AMBS to Anabaptist values and mission. When we returned to Canada, my wife Margaret and I, with our four young children, settled in Montreal and attended a Mennonite Church Eastern Canada congregation, the Mennonite Fellowship of Montreal. I served as chair of Mennonites in Quebec for quite awhile. Eventually, I joined a Mennonite and Mennonite Brethren joint affiliation congregation, a church plant, then eventually came to the Mennonite Brethren.

Why the French side? My conversion to the Christian faith – although I was a preacher’s kid, I didn’t have faith. So evangelism has always been quite important to me, I was attending Laval University when I came to faith, so my first Bible readings and my first prayers and so on were in French so that has always had a special place for me. When I was looking for a subject for my PhD thesis in church history, French protestants in Quebec captured me as a field that was fascinating and not much work done so that’s how I ended up there.

Early in the process, do you remember me asking why you were focusing on French mission in Quebec rather than writing a more generic history of Mennonites in Quebec? Why did you choose to focus on mission?

I’m a church historian. I started off with a history first of the Mennonites, then of the Mennonite Brethren. I’ve been involved with two church plants, both closed, and I’ve been around all kinds of people doing mission as I taught at an evangelical college. I was aware of a lot of unsuccessful attempts at mission in Quebec, so when I was looking at the history it was mission, and particularly French mission which was very different than the English mission, even in Quebec. The history of Mennonites in Quebec was obvious, but my interest in mission in Quebec came from my own experience, and the need to find some answers for myself. I’m not a missiologist, which I say in the book, but history teaches some things about mission. It doesn’t give the solutions, but I think it teaches some things. Maybe more the problems than the solutions.

And why the four groups – Mennonite Brethren, Swiss Mennonites, Brethren in Christ and Church of God in Christ Mennonites – instead of focusing on just one?

I did an MCC assignment with Summerbridge. Since I was church historian and working at Mennonite Fellowship of Montreal, it was suggested that I work on history, so I worked, first of all, on the history of Mennonites, the beginning of the mission and interviewing people at Mennonite Fellowship of Montreal, the pioneers there. It was a video study, aiming for the fiftieth anniversary of Mennonites in Montreal. The membership lists showed that the majority were French. When I came to teach at L’École de Théologie Évangélique du Québec (L’ETEQ), there was a conference for the 100th anniversary of Mennonite Brethren worldwide. I did something preliminary on Quebec and an article out of that.

Meanwhile La Société d’histoire Mennonite du Québec (SHMQ) hired Zacharie Leclair to do some interviews in anticipation of their 50th anniversary. It was really the two fiftieth anniversaries of Mennonites and Mennonite Brethren that sparked the research. It was the idea of the historical society to do a history of the two, but there were also two others – the Brethren in Christ, whom I knew well, but also one whom I didn’t know, the Church of God in Christ Mennonites. The pastor of that church was agreeable to give information. A group of Mennonites and Mennonite Brethren went to visit, to find out more about it. They were so different than the others. It proved fruitful to compare – each of the four groups stresses aspects of Anabaptist identity without having everything. They have interesting differences that are positive, but each one has drawbacks – on mission and in Anabaptist values in general. They are the only four groups of Mennonites in Quebec – all claim to be Anabaptist.

I’m also curious about your comparison with France. What drew you to include France in the book? How does that comparison bolster your discussion?

That’s a question that one of the reviewers suggested. Why don’t you compare them with the Baptists and the Pentecostals in Quebec instead of with France? That would be interesting in some elements, but fundamentally, partly it was because of Robert Witmer, who was very involved in the community in France. The Mennonites in France also have a link with L’ETEQ. In terms of French, most of our theological and ethical materials in French come from France. So the Anabaptists here are informed by the ones on France. Secondly, I’ve been convinced for a while that in some ways you could say the Church Growth Movement is what I see as the main problem in mission in Quebec. The Baptists and the Pentecostals both go along with the ideas of church growth, whereas Mennonites in France don’t. I became convinced that Quebec is more like Europe than it’s like the rest of North America. The context of post-Christendom is what dominates particularly in western Europe and in Quebec. France has a lot to teach Quebec, in terms of mission.

This led me to organize a colloque on the subject, then secondly this book. I think subtly, but it clearly criticizes church growth replacing it with an Anabaptist mission in an emphasis on discipleship. The Mennonite Brethren just made that step recently. When I started the book, I’d say the Mennonite Brethren were dominated by a Church Growth approach. By the time I finished it, they had turned away from it. What I realized in France was that North American missionaries knew they were going to another culture, they were better trained in French, higher standards were expected than for those coming to Quebec. When It came to Quebec, they were dealing not only with those who weren’t Anabaptist, but were post Christian. In France, they got involved in teaching and they got involved in learning the context and they didn’t expect people to easily accept the Gospel whereas in Quebec it was very different because of the North American background. Church Growth assumes that if you talk about your soul needs saving that people will respond to that. In France, I think they quickly realized that they’re not going to respond to that; they had to go about it differently. I also looked to Stuart Murray in England, as someone who has faced post Christianity longer and hasn’t had the same American Church Growth influences that we have had in Quebec.

Your book has been released in English, but will shortly also be coming out in French. Why dual language? Are the two version identical, or will readers who are able to access both version learn different things?

I wrote it in English, but the historical society here in Quebec wanted it in the two languages. The two versions are reaching different audiences. They’re not identical, but virtually. The text of the English version was finished earlier and had less revision. With the French version I was able to reorganize it at some points, add a few things, particularly pictures including coloured pictures in the French version which are not in the English edition. My favourite’s the French version.

Who do you see as your primary audiences? Who are you hoping will read Menno’s Descendants?

My first thought was that there needed to be something in English for people outside of Quebec. There isn’t much in English. I’m also writing it for mission strategists. I want to try to change the thinking of people who organize mission to Quebec. I want to honour all the people who were involved and their descendants. That’s certainly part of the audience and people who are simply interested in Quebec in general. There are also people who are related to missionaries to Quebec. I’ve talked to some of those people. It can be used by all four groups, maybe less in the Brethren in Christ, because I’m not concentrating so much on them, but it’s important for the history of other three groups. In Quebec, there have been a lot of people who have been involved in all of these churches, but are no longer there. I’d like to give them a place too, maybe even good memories of what they used to be involved in. I do meet people who say I think I have a calling to be a missionary in Quebec. I’d like them to read it before they come to see it’s a little harder than you think. There are things to take into account to be prepared for it. It’s a very different culture.

You’ve chosen a striking title. I’m intrigued with the concept of descendants. It sounds sort of genealogical rather than theological. Can you tell us how you came up with this title? What it means to you?

The title in French is just Menno au Quebec (Menno in Quebec). Menno is only mentioned one time in the text. Anabaptist is what appears often in the text, more than Mennonite, since it incorporates all four groups. But they all look back to Menno – the early Anabaptists – but they each take different aspects of Menno or of the early Anabaptists. In terms of genealogy, it’s our ancestors, in my case and for the people in Quebec, they don’t have any Mennonite ancestors; it’s all theological descent, they don’t’ have parents or grandparents that were Anabaptists, so they look back to Menno. The theological descendants of Menno. Depending which group you’re a part of, you may not see traces of Menno in the other groups, but all look back to him.

You wrote the book while working at L’École de Théologie Évangélique du Québec and with support of MCC and La Société historique mennonite du Québec. How did these institutions support your work?

MCC had a tremendous impact on all of those aspects. I worked on Summerbridge with Mennonites through MCC; SHMQ is financed by MCC; the book through Pandora is financed by MCC. MCC has been very important all the way along. Working at L’ETEQ has given me time – as a librarian I have a lot of time plus great resources on MBs. The Centre d’etude anabaptist de Montreal which sponsors Mennonite books in Quebec was sponsored by MCC in its beginning. Plus I’ve got two historians with PhDs as consultants in the SHMQ. Financially, timewise and consultants along with MCC.

As historians, we believe that history is important, that unless we know where we’ve been, we can’t possibly know where we’re going. How do you anticipate your book supporting and furthering Mennonite mission in Quebec?

I wanted to preserve the history that can get lost – documents and people. It’s important to preserve the memories. None of the churches would have the resources to write their own histories. So it was a way of preserving the various histories. Zacharie Leclair says it will be a compulsory book for new pastors to the Mennonite Brethren, so for pastors, mission strategists, hopefully in the future with more information they’ll be able to avoid some problems. I don’t have solutions, but to identify some of the questions and some of the false steps that have been taken in the past and danger points. Hopefully those will be helpful. Another aspect is most French don’t know anything, or very little, about Anabaptists, so people in the churches are learning about Anabaptism. I also felt it was important to highlight missions that were in the same area as Mennonites and MBs started, one hundred years before. I thought that was important to show that these earlier missions faced some of the same obstacles. They persevered, although most disappeared. That can happen. But the Mennonites and MBs weren’t the first Protestant missionaries in the area. We can learn from the history that the church didn’t start yesterday. I also got into my book some things that others wouldn’t include. I also included a section on immigrant churches.

How can we access the book? The English version? The French version? Will it be available electronically? On kindle?

Regarding the English version, Pandora suggests ordering from Amazon. https://www.pandorapress.com/#/

The French version is being published by La Société d’histoire du protestantisme franco-québécois https://www.patrimoine-religieux.qc.ca/en/publications. It should be available by the middle of March At l’ETEQ (eteq.ca).

Electronic versions are still in conversation.

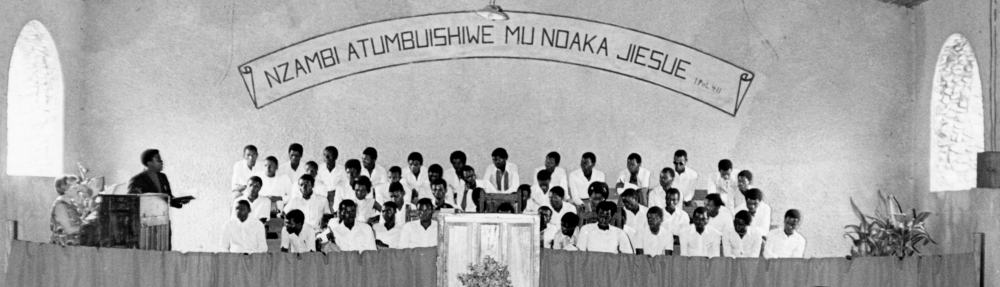

**Finally, a note of explanation regarding the photos. The first photo is the book’s cover; The second depicts Lucille Marr interviewing Richard Lougheed; third is a group of Quebec youth taken in the sixties; fourth is the first Mennonite baptismal candidates. The latter two photos appear in black and white in the English version of the book and in colour in the French version.