Janneken Smucker

In the early 1970s, art enthusiasts began to display Amish quilts from the early twentieth century on the walls of apartments, galleries, antiques shops, and museums, noting how their strong graphics and minimalist designs resembled abstract paintings of the post-World War II period. Prior to the 1970s, no one really had paired the adjective Amish with the noun quilt. Yet with this cultural dislocation, Amish quilts shifted in status from special, heirloom bedcovers, kept folded in chests and treasured as gifts between family members, to cult objects in demand within the outside world. Amish families responded by selling their “old dark quilts,” happy to have extra money that could be split among descendants in a way a quilt could not be, and glad to remove objects now considered “status symbols” by outsiders from their homes. In turn, Amish entrepreneurs began making quilts to sell to consumers, creating a quilt industry that could capitalize on increasing tourism to settlements and the growing fascination with Amish-made bedcovers.

Center Diamond, Unknown Amish maker, Circa 1920-1940, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Machine pieced, hand quilted. International Quilt Study Center & Museum, University of Nebraska – Lincoln; Jonathan Holstein Collection, 2003.003.0072

This intersection between the Old Order Amish and the worlds of art, fashion, and commerce is a central tension of my recent book, Amish Quilts: Crafting an American Icon (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013). As I worked on this book, I frequently imagined it as an exhibition, with the objects themselves serving as evidence and touchstones within the narrative. With this mindset, I was thrilled when the International Quilt Study Center & Museum at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln invited me to guest curate an exhibit of Amish quilts. This exhibit, Amish Quilts and the Crafting of Diverse Traditions opens October 7, running through January 25, 2017.

Since the 1971 landmark exhibition Abstract Design in American Quilts at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the typical mode of display for quilts in museum settings has been on walls, hung vertically like the paintings to which Amish quilts in particular have often been compared. As I began work translating my research into an exhibition, I struggled to figure out how to simultaneously interrogate the de-contextualization of Amish quilts while participating in the process itself. I did not want to simply hang quilts on walls as they had been for the last 45 years, where too often they appear merely as great works of design, rather than as objects symbolic of the Amish emphasis on community, mutual aid, and Gelassenheit. But what could we do instead that would fulfill the museum’s dual mission of showcasing quilts’ artistry and cultural significance?

All public history requires careful and deliberate communication; it’s intended to translate complex ideas into meaningful and engaging forms. Working with the IQSCM staff, we’ve developed ways to communicate the multiple contexts of Amish quilts. When museum-goers enter the gallery, they will indeed still see quilts hanging on walls. But in the center of one gallery, there will be an object strangely foreign to most quilt exhibits, Amish or otherwise: a bed. My parents, who live in Goshen, Indiana, generously loaned the museum the ¾ size four-poster rope bed that descended in my mother’s family from our Amish-Mennonite ancestors. Made in the family of Solomon Beachy from Holmes County, Ohio, c. 1840-1860, the bed will be the perfect showcase for an early twentieth-century quilt made by Barbara Yoder.

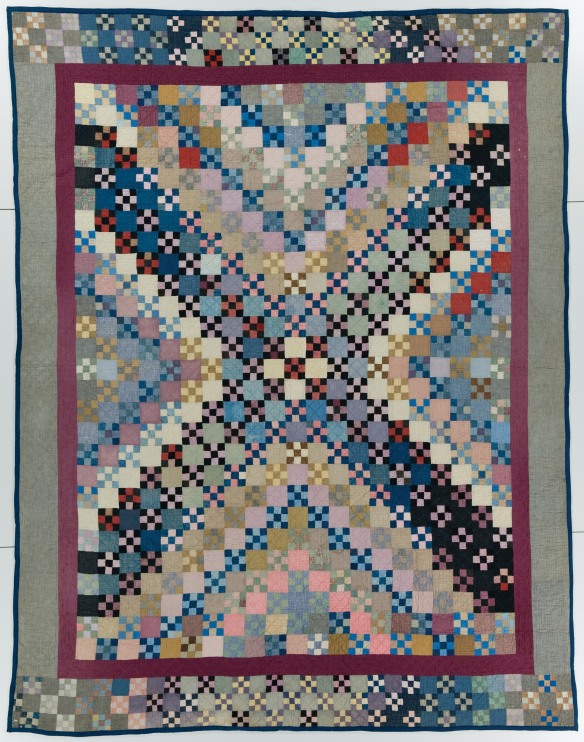

Nine Patch, Made by Barbara Yoder (1885-1988) Circa 1920, Made in Weatherford, Oklahoma, Machine pieced, hand quilted. International Quilt Study Center & Museum, University of Nebraska – Lincoln; Gift of the Robert & Ardis James Foundation, 2005.039.0005

But the Amish origins of these quilts are not the only context through which I interpret them. The lives of these objects since they left Amish homes are equally intriguing, and I explore them as influential within contexts of art, consumer culture, and fashion. The Esprit clothing company, well-known for its color block designs of the 1980s, was home to a significant corporate collection of Amish quilts which hung on the walls throughout its San Francisco headquarters. We will hang a quilt that Esprit once owned alongside a mannequin dressed in one of my personal favorite objects of material culture—this amazing Esprit vest that in my mind was clearly inspired by Amish quilts.

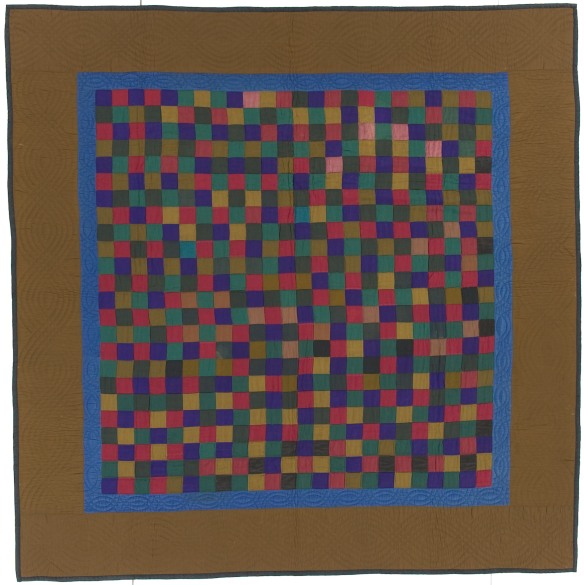

One Patch/Checkerboard, unknown Amish maker, circa 1900-1920, machine pieced, hand quilted. International Quilt Study Center & Museum, University of Nebaska-Lincoln, Ardis & Robert James COllection, 1997.007.0469

Espirit women’s vest, circa 1985, United States. Collection of Janneken Smucker

We will also display images of contemporary Amish quilt shops, along with two new quilts made for the consumer market, with designs in clear contrast to the “cult objects” with which art enthusiasts became enamored. I also had the pleasure of attending the Gap (Pennsylvania) Fire Company Sale last March, known locally as a mud sale. We include photographs from this event, which supports the local volunteer fire company, along with quilts I acquired on the museum’s behalf there (not a bad gig — bidding with someone else’s money). The quilts include a white and lavender Dahlia quilt from the mid-twentieth century, complete with intricate lavender hand quilting and ornate fringe—not what we expect from an Amish made quilt, but one of the many styles that have co-existed within Amish communities.

Dahlia, Unknown Amish maker, circa 1940-1960, probably made in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. International Quilt Study Center & Museum, University of Nebraska – Lincoln Gift of the Robert & Ardis James Foundation, 2016.030.0003

I have relished the challenge of translating my research into this physical form. I hope my thesis—that the craft of Amish quiltmaking has never fossilized, but has been a living, evolving, and diverse tradition, adapted by creative quiltmakers, capitalized upon by businesswomen eager to earn a livelihood, and embraced within both Amish communities and the broader artistic and consumer worlds—comes through. But even if my message is lost, the quilts look great, as they always have, both in and out of context.