Ben Goossen

Recent revelations that Mennonites participated in the crimes of National Socialism seem to fly in the face of common beliefs about this historically pacifist Christian denomination. Mennonites today are often advocates for peace. So what are we to make, for example, of a forthcoming book from the University of Toronto Press entitled European Mennonites and the Holocaust? A gulf looms between what we believe we know about peaceful Mennonites in the twenty-first century and what historians have begun revealing about the entanglement of a substantial minority within that same community with National Socialism during the 1930s and ‘40s. How can we bridge the gap? One path is to ask why this story has not been widely told until now. Who hid it and how?

After the Second World War, the primary narrative that Mennonite leaders in Europe and North America crafted about their churches’ activities in the Third Reich emphasized repression and hardship. The denomination’s leading aid organization, Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), worked during the late 1940s and early 1950s to help resettle thousands of European Mennonites who had become displaced as a result of the war. MCC relied on financial and legal assistance from larger refugee agencies affiliated with the United Nations in order to pursue this task. In dealing with their United Nations colleagues, MCC officials insisted most of their wards “were brutally treated by the German occupation authorities” and “did not receive favored treatment.”1

One of Mennonite Central Committee’s star witnesses was a refugee named Heinrich Hamm. Like tens of thousands of other Mennonites who had experienced the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe, Hamm was from Soviet Ukraine, and he had retreated westward with German troops in 1943 to avoid again coming under communist rule as Stalin’s Red Army advanced. Five years later, Hamm had become an MCC employee, helping to run a large refugee camp in occupied Germany. Hamm wrote down a version of his wartime experiences that aligned with MCC’s overall message that its charges deserved aid. MCC’s Special Commissioner in Europe passed to United Nations officials Hamm’s story of evacuating from Ukraine to more western areas:

It is quite an erroneous idea to think that all Mennonites were brought to Poland to be settled on farms. I and my family came to a camp Preussisch-Stargard in the Danzig area. Immediately representatives of various works and concerns came to fetch cheap labour. I had to work in a machine factory where I remained until the end of the war. Besides the four Mennonite families many Ukrainians, Frenchmen and Poles worked there also. There was no difference in the way these various national groups were treated.2

The efforts by Mennonite Central Committee to portray refugees like Heinrich Hamm as victims of Nazism were largely successful. Based on statements from MCC officers and many migrants themselves, refugee agents affiliated with the United Nations believed that “the majority of those [Mennonites] who found themselves in Germany at the end of the war had not come voluntarily to that country. They were deported alongside other Russians to be used as slave labourers.”3 As another evaluation concluded, Mennonites were fundamentally “an un-Nazi and un-nationalistic group.”4 MCC ultimately succeeded in relocating most of the refugees under its care with United Nations assistance to new homes in West Germany or overseas, mostly in Canada and Paraguay.

But should we, like United Nations refugee agencies seven decades ago, trust statements written after the Third Reich’s fall by Mennonite individuals such as Heinrich Hamm? When he wrote his account for MCC, Hamm was fifty-four years old. He was not some young hothead. He was a leader in the Mennonite church. He was an MCC employee with deep ties to the denomination’s respected aid community on both sides of the Atlantic. Hamm should have been as trustworthy as anyone MCC could have put forward to speak truthfully and extensively about the experiences of tens of thousands of fellow Mennonites in Eastern Europe during the Second World War. The United Nations took Hamm at his word. We today, however, should take a more skeptical look.

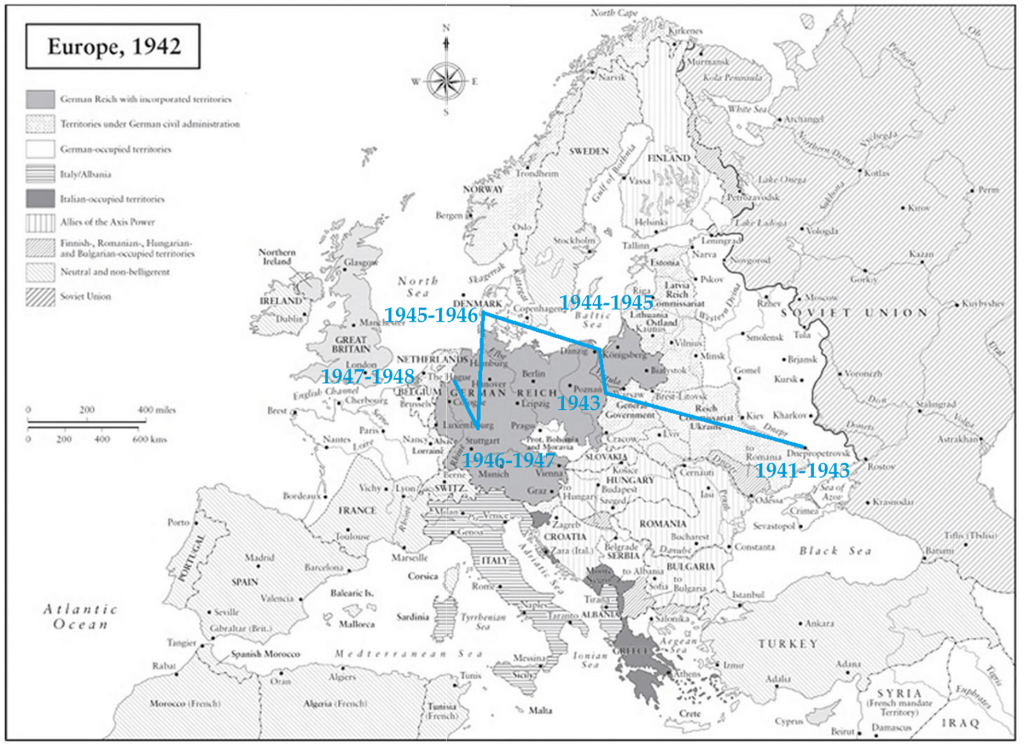

I have been following Heinrich Hamm’s wartime paper trail for the past seven years. It is not easy to track the movements of someone so mobile as Hamm. I now know that Hamm was born in Tsarist Russia in 1894. He served as a medic in the First World War and took up arms as part of a Self Defense unit during the Russian Civil War, abandoning pacifism like many other young Mennonite men. When Bolshevism emerged victorious, Hamm lost his farm near the Ukrainian city of Zaporozhe. He and his family moved to another city, Dnepropetrovsk, after Stalin’s rise. Hamm continued working in Dnepropetrovsk after the Nazi invasion of 1941. He eventually left Ukraine with his family, and in 1944, they settled in a village called Stutthof on the Baltic coast.

Another document I encountered while researching Mennonite history prompted me to suspect that the postwar autobiographical sketch Hamm penned for MCC might obscure more than it revealed. This other document had been written shortly after Hitler’s invasion of Soviet Ukraine by an “Ethnic German Heinrich Hamm.” Preserved in the records of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, the six-page typed manuscript tells of horrors experienced under “Jewish-Bolshevik rule.” It argues that the USSR repressed Ethnic Germans more than other groups. It describes how young men were shot or deported and how mismanagement brought economic ruin to all Ukraine. The author was unsparing in his conviction about whom to blame:

This is how the Jewish Bolshevik beasts destroyed German families [during communist times]. The expression ‘beasts’ is not even correct, since animals kill for the sake of nourishment, while these Jewish murderers and misbegotten bastards kill and annihilate for sport, practicing the worst kind of cruelty as their life’s handiwork.5

Could these be the words of a later MCC employee? An upstanding pillar within the worldwide Mennonite community? When I first saw this document, I was not convinced it had been written by the same Heinrich Hamm. Hamm was a common surname among Ukraine’s Mennonites and Heinrich a common first name. Surely there were multiple Heinrich Hamms. Nor was I sure that the author was even Mennonite at all. His report to Nazi officials mentioned other people with names common among Mennonites, but the document referred only to “Ethnic Germans,” not to Mennonites explicitly. Given the repression of Christianity in the Soviet Union in the proceeding decades, perhaps the author no longer identified with what had likely been his childhood faith.

I wondered, moreover, what should I make of the virulent antisemitism of this wartime Heinrich Hamm? Most published literature I had read about Mennonites in Ukraine claimed that they had not been particularly antisemitic. One historian characterized anti-Jewish prejudices among this group as “relatively benign.”6 But Hamm’s antisemitism was unrelenting. The report stated that Hamm lived in Dnepropetrovsk. Less than a month earlier, Nazi death squads shot ten thousand of that city’s Jews.7 The murder of Jews around him made Hamm’s concluding remarks chilling: “Only those who experienced [Soviet tyranny] can fully grasp the phrase, ‘Liberation from the Jewish yoke of Bolshevism,’ in its truest sense.”8 He finished by praising Hitler and all German soldiers.

My next clue was a 1943 letter—also penned by a “Heinrich Hamm”—posted from a refugee camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. This letter seemed to provide a link between the Hamm who had denounced Jews at the height of the Holocaust in Ukraine and the man who subsequently worked for MCC, claiming after the war that Mennonites were an un-Nazi group that suffered under the Third Reich. The author of this letter was clearly a Mennonite. He had relocated westward with other Mennonites from Ukraine to escape the advance of the Red Army. The author said he had traveled from Dnepropetrovsk, and details of his story overlapped with the account written two years earlier for Nazi occupation officials by a man of the same name in the same Ukrainian city.

The 1943 letter convinced me that Heinrich Hamm was not only a practicing Mennonite; he was a denominational leader. It also confirmed that this man—who would go on to work for MCC—was implicated in Nazi crimes. Hamm and his family were among the first Mennonite refugees to be relocated from Ukraine to Nazi-occupied Poland after the contraction of the Eastern Front. Temporarily housed near the city of Litzmannstadt in the wartime Wartheland province, Hamm wrote to a contact well connected with other Mennonites across the Third Reich. Copies of his letter soon circulated widely among the country’s church leadership. Part of Hamm’s letter even appeared in print, helping inspire humanitarian support for the refugees arriving from Ukraine.

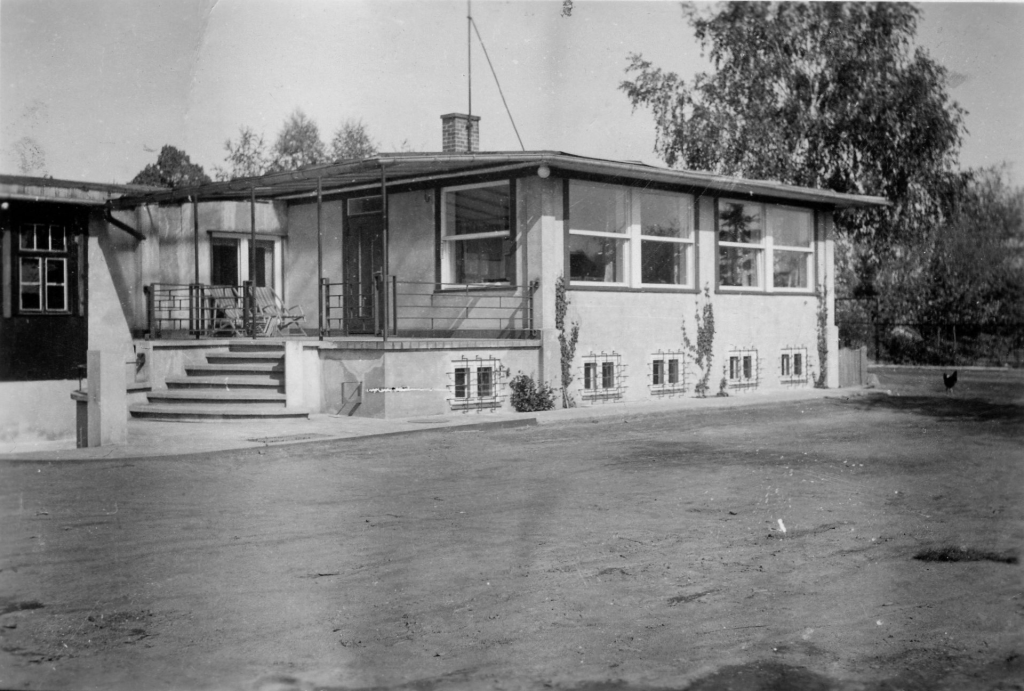

Hamm reported that he and fellow refugees from Ukraine had been well received in Wartheland: “Upon arrival, we experienced unexpected love and a moving reception. Our camp—if it can even be called that—lies in the forest near Kirchberg (14 km. east of Litzmannstadt) and consists not of barracks encircled by barbed wire, as many expected, but of beautifully appointed houses (formerly for Jewish summer vacationers).” Hamm acknowledged that not all were satisfied with their new quarters. But he disparaged complainers as racial dregs. The “true Germans,” he wrote, “thank God and the Führer daily with tears in their eyes for the great privileges they enjoy.”9 In his view, the best Mennonites were those most thankful to receive plunder from murdered Jews.

Far from receiving criticism from Germany’s Mennonite leadership, Hamm’s 1943 letter helped integrate him into the local denominational fold. Mennonites who had lived in Germany since Hitler’s rise to power had enjoyed the privileges of racial hierarchy for over a decade. That these same advantages would be extended to fellow German-speaking Mennonites from Ukraine in the form of homes and goods taken from Holocaust victims seemed only natural by the middle years of the war.10 Hamm was intimately acquainted with Mennonite life in Ukraine, and he had ties to occupation officials.11 When religious leaders from Germany traveled to Poland in 1944 to meet with Nazi politicians about new waves of refugees from the east, they first consulted Hamm.12

By early 1944, Hamm and his wife, Anna, had moved from the formerly Jewish summer camp near Litzmannstadt to the coastal town of Stutthof, two hundred miles to the north. Stutthof had a longstanding Mennonite population, including one of Anna’s aunts. In Stutthof, Hamm became friendly with a prominent Mennonite businessman named Gerhard Epp. Prior to the First World War, Epp had worked in Russia, and he remained greatly interested in Mennonite coreligionists from the Soviet Union. Epp offered Hamm a job in a large machine factory that he owned and operated. This was the very establishment that Hamm would later mention in the memo he wrote for MCC, claiming he was coerced into providing cheap labor for greedy German war profiteers.

Closer inspection reveals Hamm was neither a lowly laborer nor does he seem to have opposed war profiteering that actually did occur in Epp’s factory. Three years after the Third Reich fell, shortly before boarding a steamship bound for Canada, Hamm wrote a long letter to his two sons. They had been serving in German uniform, and both had gone missing in the last months of the war. Hamm did not know when or if he would ever see his sons again. But he left his letter with a local Mennonite leader for safekeeping, hoping that if either of his sons ever resurfaced, they would read it. Hamm’s letter is dated July 23, 1948. He signed it just days after authoring his exculpatory memorandum for MCC. Writing privately to family, he told a very different story.

Hamm’s letter to his lost sons told of his final days in Stutthof, before the Red Army’s advance forced him to flee with his wife and her aunt, along with thousands of other Mennonites and non-Mennonites by ship across the Baltic to Denmark. In the winter of early 1945, Soviet air raids wrought havoc on nearby large cities like Danzig, driving city dwellers to the countryside even as others arrived pell-mell from the east. Gerhard Epp shipped his machinery west and converted his factory into a makeshift refugee camp. Hamm reported that Epp and his entire staff worked frantically to save the needy. The packed factory halls offered good targets for Soviet airmen, Hamm reported, and every bomb that struck the establishment killed or wounded hundreds:

The great number of bodies and the frozen ground made it impossible to bury them, and so specially appointed commandos for clearing away bodies brought these to the concentration camp for gassing [Vergasung].13

This casual reference to an unnamed nearby concentration camp is curious. Hamm seems to have expected his sons to understand the reference. Having visited their family in Stutthof before their final deployment, Hamm’s sons would have known about the large Stutthof concentration camp, which had been established in 1939 in connection with Germany’s invasion of Poland and which over the next five years would become a major site of slave labor and murder in Hitler’s empire of death. Gerhard Epp’s factory had grown along with this concentration camp. Epp served as a general contractor for the camp, and he leased hundreds of prisoners to produce armaments in his factory. Jews and other inmates were the true cheap labor. Hamm helped oversee their slavery.14

Hamm later expressed regret for the death and dying that pervaded the Epp factory in Stutthof. Yet he explicitly named only German victims of Soviet air raids, not Jewish concentration camp prisoners. “[M]uch, much blood of innocent women and children flowed on Epp’s land,” Hamm told his sons. “Uncountable, nameless dead… No one asked who they were, where they came from, nothing was recorded.”15 One wonders about the goal of this private postwar accounting. Was Hamm helping himself forget about Jews worked to the bone in Epp’s factory by recalling refugees he and Epp tried to save? His use of the word “gassing” suggests this possibility, since bodies of refugees could have been cremated, whereas exhausted Jews would have been gassed.

What is clear is that the Mennonite-owned factory in Stutthof was a place of terror. For hundreds of prisoners enslaved there, the factory’s Mennonite managers were responsible for much of that terror. It is also clear that after the war, Hamm tried to distance himself from this responsibility. He instead emphasized the suffering of his own family, which fled Stutthof in April 1945. As they crossed the Baltic under cover of night, a Soviet submarine torpedoed their ship. Hamm praised God for allowing the damaged vessel to make it to Denmark. The family remained in Denmark for the next eighteen months. Hamm emphasized his gratitude for the comfort he found during these lean times through worshiping with fellow Mennonite refugees and other Christians.

Hamm remained in touch with Mennonites in multiple countries during the early postwar years. From Denmark, he wrote to relatives in Canada, who published his communication in a church newspaper. Letters and material goods soon arrived both for the Hamms and other Mennonites in the area. Hamm coordinated this aid, disbursing dozens of food packets from North America to fellow refugees. When his family received permission to leave Denmark for Germany, they lived with Mennonites in Bavaria. Eight months later, the director of a Mennonite Central Committee refugee camp in Gronau, near the Dutch border, invited Hamm to be his deputy. Hamm took the job, and he worked for MCC in Gronau for nearly a year until leaving to join relatives in Canada.

Tracking Heinrich Hamm and his wartime activities has taught me that catching a Mennonite Nazi is hard work. Piecing together Hamm’s past took many years of laborious sifting through thousands of pages of historic documents. I found pieces of Hamm’s story scattered across half a dozen archives in four countries. The reason this search took so long and required such effort is that Hamm did not want me or anyone else to know his full tale. Collaborating with Nazism made sense to Hamm during the Second World War, when he denounced Jews in Ukraine, lived in housing confiscated from Holocaust victims in Poland, and helped to administer a factory run with slave labor in Stutthof. After the war, Hamm was not fully honest even with his own sons.

The rewards of studying Hamm’s complete wartime trajectory—not just what he wanted others to learn afterwards—are substantial. Hamm and his colleagues at Mennonite Central Committee wanted United Nations-affiliated refugee organizations and other interested parties to think that any collaboration by members of the denomination with National Socialism was exceptional and insignificant. They implied that if some young men had perhaps gotten carried away, surely this was because they had been drawn away from their faith during earlier experiences in the Soviet Union through the atheist policies of Bolshevik rule. This narrative may seem compelling if we only consider documents written after the war. But wartime records do not corroborate this story.

Hamm was a leader at the heart of Mennonite institutional life in Europe both during and after the Second World War. He and his family had certainly suffered under the Bolshevik regime. There is no question that he and tens thousands of other Mennonites experienced atrocities in the Soviet Union, and that this history of suffering conditioned their positive reception of National Socialism. Indeed, Hamm’s wartime writings show that he considered his support for the most heinous crimes of Hitler’s state to be directly related to his own efforts to aid fellow Mennonites. Hamm saw Jews and Bolshevism as being part of a single evil cabal that threatened his ethnic and faith communities, and he welcomed Nazi efforts to redistribute Jewish plunder as welfare.

Understanding Hamm’s wartime activities also helps to clarify the significance of Mennonite Central Committee’s European refugee operations. Were we to consider only MCC’s postwar reports to bodies like the United Nations, we might assume that the denomination’s premier aid organization was acting in good faith—that leaders were unaware of the Nazi collaboration of refugees like Hamm. But this reading cannot be supported. In a very literal sense, Hamm was MCC, a paid employee and spokesperson. And that was precisely the point. The very purpose of MCC’s refugee program was to assist people facing legal or material hardships because of their associations with Nazism. Employing wartime leaders like Hamm provided valuable expertise.16

Catching a Mennonite Nazi is not easy. It is not the kind of thing most people can accomplish in their spare time. It is only possible because of the enormous resources that states, universities, and churches have put into building and maintaining archival collections. Accessing these files often requires professional skills, such as the ability to read multiple languages. Guessing when a historical person may not have been telling the truth requires familiarity with what scholars have already written. And following up on such hunches frequently demands financial support from competitive grants. At a time when the humanities are increasingly under pressure, it is more important than ever to affirm the value of institutional support for deep investigative research.

The reach of the far right is often longer than we think. It has included influential leaders within the Mennonite denomination, including in its best-known humanitarian aid organization, MCC. That knowledge alone should justify robust support for strengthening commitment to academic scholarship in our current time of resurgent global intolerance and repressive authoritarianism.

Ben Goossen is a historian at Harvard University. He is the author of Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, published in 2017 by Princeton University Press. Thanks to Laureen Harder-Gissing for providing sources for this essay and to Madeline J. Williams for her comments.

1 C.F. Klassen, “Statement Concerning Mennonite Refugees,” July 19, 1948, AJ/43/572, folder: Political Dissidents – Mennonites, Archives Nationales, Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, France (hereafter AN).

2 Quoted in ibid. Hamm signed other documents on MCC’s behalf while working at the Gronau refugee camp. For example, Heinrich Hamm to Walter Quiring, September 29, 1947, Cornelius Krahn Papers, box 5, folder: Walter Quiring Correspondence 1946-50, Mennonite Library and Archives, North Newton, Kansas, USA.

3 Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, “Mennonite Refugees from Soviet Russia,” AJ/43/49, AN.

4 Martha Biehle to Herbert Emerson, August 9, 1946, AJ/43/31, AN.

5 Heinrich Hamm, “Schilderung vom Volksdeutschen,” November 12, 1941, Captured German and Related Records on Microfilm, T-81, roll 606, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, USA (hereafter NARA). Subsequent research confirms that this report was written by the same Heinrich Hamm who later worked for MCC. In ibid., for example, the author identified his father-in-law as David Schröder. David Schröder was also listed as Hamm’s father-in-law in genealogical materials submitted at the time of his (successful) application for German citizenship in Litzmannstadt. Heinrich Hamm, “Feststellung der Deutschstämmigkeit,” October 11, 1943, Einwandererzentralstelle Collection, A33420-EWZ50-CO46, Mennonite Archives of Ontario, Waterloo, ON, Canada. Notably, Hamm listed “men[nonite]” as his religious denomination on multiple documents submitted to Nazi offices. See for example a racial evaluation completed in Preußisch Stargard: “Hamm, Heinrich,” February 1, 1944, A3342-EWZ56-CO27, NARA.

6 Harvey Dyck, “Introduction and Analysis,” in Jacob Neufeld, Path of Thorns: Soviet Mennonite Life under Communist and Nazi Rule (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 47.

7 SD, “Ereignismeldung UdSSR Nr. 135,” November 19, 1941, R 58/219, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, Germany.

8 Hamm, “Schilderung vom Volksdeutschen.”

9 Heinrich Hamm to Franz Harder, October 6, 1943, German Captured Documents Collection, Reel 290, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA (hereafter LoC). Hamm’s contact, Franz Harder, was a Danzig-based genealogical researcher. Since 1942, Harder had been helping Hamm to compile a genealogical list proving his Aryan ancestry—a document useful for Hamm’s wartime employment in Nazi-occupied Ukraine as well as his eventual application for German citizenship. Hamm’s letter came to the attention of the leadership of Germany’s two largest church conferences via Benjamin Unruh to Vereinigung and Verband, October 18, 1943, Vereinigung, box 3, folder: Briefw. 1943, Mennonitische Forschungsstelle, Bolanden-Weierhof, Germany (hereafter MFS). It subsequently appeared in print as Heinrich Hamm, “Die Umsiedlung der Volksdeutschen aus Dnjepropetrowsk im September 1943,” Nachrichtenblatt des Sippenverbands Danziger Mennoniten-Famlien 8 (December 1943): 3-4.

10 Thousands of Mennonites in Ukraine had already received gifts of clothing and household goods taken from Holocaust victims, including Jews shot by mobile killings squads in Ukraine as well as others deported to industrial-scale concentration camps in Nazi-occupied Poland. Some Mennonite families in Ukraine had also moved into houses made available by the murder of previous Jewish residents. Privileges provided by Nazi occupiers to Ukraine’s Mennonites thus already depended on mass expropriation of supposed non-Aryans, so in 1943 when the retraction of the Eastern Front forced tens of thousands of Mennonites and other Ethnic Germans westward, the redistributive welfare practiced by Hitler’s functionaries again relied on plunder acquired through large-scale racial crimes. The Governor of the District of Galicia, for example, wrote during high-level debates about where to resettle Mennonites from Chortitza: “New settlements can currently only be facilitated through radical removal of the local population with no possibility of return…. In the longer term, around 20,000 hectares [50,00 acres] for settlement purposes could be made available through use of the former Jewish properties that are now under German administration.” Otto Wächter to Rudolf Brandt, October 21, 1943, T-175, roll 72, NARA.

11 For instance, a handwritten remark on a letter from Franz Harder to the German Foreign Institute identified Hamm as a confidant of Karl Stumpp, who led a Dnepropetrovsk-based commando of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. Franz Harder to Deutsches Ausland-Institut, Forschungsstelle Danzig des DAI, and Kurt Kauenhowen, October 10, 1943, German Captured Documents Collection, reel 290, LoC. On Stumpp, see Eric Schmalz and Samuel Sinner, “The Nazi Ethnographic Research of Georg Leibbrandt and Karl Stumpp in Ukraine, and Its North American Legacy,” Holocaust & Genocide Studies 14, no. 1 (2000): 28-64.

12 “I now also intend to travel to Stutthof [prior to meeting with the political leadership of Reichsgau Wartheland] to visit Gerhard Epp and Heinrich Hamm (from Dnepropetrovsk). The latter has resettled there from Litzmannstadt. Would you come with me?” Benjamin Unruh to Abraham Braun, February 23, 1944, Nachlaß Benjamin Unruh, box 4, folder 21, MFS. Unruh and Braun visited Epp and Hamm in Stutthof from March 23 to 25, 1944. Benjamin Unruh “Bericht über Verhandlungen im Warthegau im März 1944,” March 30, 1944, Nachlaß Benjamin Unruh, box 4, folder 21, MFS.

13 Heinrich Hamm to Benjamin Unruh, July 23, 1948, Nachlaß Benjamin Unruh, box 2, folder 7, MFS.

14 Gerhard Rempel, “Mennonites and the Holocaust: From Collaboration to Perpetuation,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 84, no. 4 (2010): 512-525. Although Hamm did not precisely describe his duties in Epp’s business (which he called “our factory”), he appears to have acted in an administrative capacity. “How wonderfully [God] saved us,” he remembered. “How often shards and bullets flew into our office, where I worked.” Hamm to Unruh, July 23, 1948.

15 Ibid. On the evacuation of Stutthof, see Danuta Drywa, “Stutthoff: Stammlager,” in Der Ort des Terrors: Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, vol. 6, ed. Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2007),516-520; Marcin Owsiński, “Die Deutschen in Stutthof und Sztutowo,” in Die deutsche Minderheit in Polen und die kommunistischen Behörden 1945-1989 (Paderborn: Schoeningh Ferdinand, 2017), 292-296.

16 Hamm reported that as deputy director of the MCC’s Gronau refugee camp, where he worked from August 1947 until July 1948, his major activities included establishing a catalogue of all known Mennonite refugees in Europe and corresponding with multiple Allied governments to release Mennonite prisoners of war. “The MCC was able to secure many an early release for these men [who had served in Hitler’s armies] from all Allied authorities,” Hamm wrote of his work. “How radiant with joy all these boys were when they arrived in Gronau, where they were warmly welcomed.” Hamm to Unruh, July 23, 1948. Hamm and his family remained connected to the Mennonite church and to trans-Atlantic refugee operations after arriving in Canada in 1948. See for example Hans Werner, “Integration in Two Cities: A Comparative History of Protestant Ethnic German Immigrants in Winnipeg, Canada and Bielefeld, Germany, 1947-1989” (PhD diss., University of Manitoba, 2002), 111-112.

When people are invested in and benefit from the status quo, they care more about maintaining the status quo than the price “others” have to pay in order for their interests to continue. We believe the lies to cover up the uncomfortable truth. We do not want to believe the truth because it may mean we have to give up our “freedom” for the sake of other’s emancipation. We need to be diligent and keep awake to stave off being co opted by the “powers and principalities,” justifying our positions based on an interpretation of the Christian faith that colludes with those self same powers.

LikeLike

I am very familiar with Mennonites and their society, ethics and practices, but am devastated by this article. What was once the pinnacle of true Kingdom living is now an empty shell. Leaves me feeling hollow.

LikeLike

Fascinating, disheartening, and showing that in spite of fairly robust self-congratulation at times, Mennonites are only human. I suspect many if not most of us under the terrifying cultural and political forces of Nazism would act in self-interest and contrary to our own convictions. Thank you for the laborious research. I add my tiny voice to “robust support for strengthening commitment to academic scholarship in our current time of resurgent global intolerance and repressive authoritarianism.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

This article makes very sad and very humble. I have not past the test . It reminds me how important it is to live every day being “poor in spirit”

LikeLike

Ben, I wished that you would have highlighted your indebtedness to Gerhard Rempel’s groundbreaking research into Heinrich Hamm in his unpublished manuscript, which you cite in your book, Chosen Nation. Rempel was the first person to attempt a comprehensive treatment of Soviet Mennonite collaboration in the Holocaust and his contribution to this important field of research deserves to be recognized.

LikeLike

Hi Aileen – I hope my overall argument is clear: it takes tremendous resources and many hands and eyes to track down these kinds of stories! Gerhard Rempel’s important research is of course cited here. I might add that Peter Letkemann first sent me a copy of Hamm’s 1941 report. Ted Regehr’s research pointed me to the UN materials in Paris. John Thiesen’s generosity and decades of expertise have been invaluable in navigating both the US federal archives and the (amazing) Mennonite Library and Archives in Kansas. Laureen Harder-Gissing provided documents for this essay, specifically. I’m immensely grateful for the principled, painstaking work of dozens of archivists and historians, yourself included, without whom our knowledge of this past would be poorer and our collective wisdom less robust.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your diligence and hard work in researching this. As all my grandparents came to Canada as a direct result of MCC, I now want to re-read my Opa’s autobiography and read between the lines. Mennonite privilege.

LikeLiked by 3 people

What sort of response have you received from the families of people like Heinrich Hamm, Benjamin Unruh, or others who’s activities with National Socialism can be documented? Has there been denial, sad acknowledgment, or just silence?

LikeLiked by 1 person

My Ethnic German family were Living in the Sudetenland. We weren’t Mennonites, but our family were Union Laborers and Socialists both. The NAZIs weren’t kind to either. However that also split our family politically because while some put on German Military uniforms, others wound up in Concentration Camps. At least one fought at Stalingrad with the illfated 6th Army, ending up as a Prisoner in a Siberian Gulag for several years. Another became a Double Agent in the employ of the Russians and was executed at Mauthausen. Yet another was in the Kriegsmarine, winning an Iron Cross for heroism. Another was eventually liberated by American Soldiers from Dachau. Recently I had occasion to receive some photos of her family during their life in the Sudeten. One photo included my Grandfather who I had only met for the first time in 1994. In one photo he wore some semblance of a uniform which I came to realze placed him as a member of what was known as the Sudeten Volks FreiKorp, which was a Partisan organization that created havoc for the Czechs and even carried out assassinations and acts of sabotage. It’s a strange thing to find that past History has such close ties. I can honestly say that of those members of our family that chose to fight for Hitler and NAZIsm, I am not proud at all. I have far more sympathy for those who were mistreated by the NAZIs. I doubt that there were few inEurope who came away from WWII unscathed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if Mennonites today feel the weight of their tainted history or if they feel any responsibility to reconcile that history with their stated beliefs. Thanks for your continued excellent work bringing these dark places into the light of day.

LikeLiked by 1 person