A Mennonite named Abraham Esau headed the Nazi nuclear program during much of the Second World War.1 Esau’s activities contributed to Albert Einstein’s decision to warn US President Franklin Roosevelt on August 2, 1939, that Hitler’s government was studying atomic chain reactions that might lead to “extremely powerful bombs.”2 The program Esau ran in the Third Reich constituted a prime justification for the United States’ secret Manhattan Project, which produced the first atomic weapons. After the war, the North American-based Mennonite Central Committee helped rehabilitate Esau, who in turn downplayed Mennonite involvement in Nazism.

Abraham Esau was born in 1884 to a respected Mennonite family in eastern Prussia. His paternal grandfather was elder of the large Tiegenhagen congregation. He was raised by his father, a local bureaucrat.3 During Esau’s adolescence, Mennonites across Germany adopted nationalist ideals.4 Esau, perhaps more than anyone else, benefitted from the denomination’s new enthusiasm for higher education and military service. After receiving his doctorate in 1908, he performed noncombatant service as a radio physicist. He became involved in an ambitious state-sponsored project to confront British power by building a global wireless network to spread German news.5

Esau cut his teeth combining German expansionism with large-scale physics projects in colonial Africa. In 1914, on the eve of the First World War, he traveled to the German colony of Togo to install a massive radio station, which he subsequently destroyed in the face of invading French troops. French captivity deepened Esau’s nationalism, as did the postwar Treaty of Versailles, which gave much of his native Prussia to a new Polish state. In 1925, Esau joined the faculty at the University of Jena. There, he developed a physics research program. He discovered how to use radio waves for therapy, was nominated for a Nobel Prize, and became university president.

The rise of Adolf Hitler in 1933 proved fortuitous for Esau. Joining the Nazi Party in May, he strengthened his presidency at Jena within the new political order. The governor of Thuringia appointed Esau a State Councilor, giving him access to powerful Nazi leaders. Meanwhile, his knowledge of radio physics made him valuable to the Propaganda Ministry, for which he served as an advisor. By the end of the decade, Esau had relocated to Berlin, where he headed the Reich Physical and Technical Institute. As a prominent science administrator with impeccable political credentials, Esau eagerly followed new discoveries in the field of high-energy atomic physics.

Esau headed the Nazi nuclear program briefly in 1939 and then again from March 1942 to the end of 1943.6 In April 1939, he organized a conference on nuclear chain reactions through the Reich Ministry of Education, where he announced plans to collect all uranium in Germany. With the outbreak of the Second World War in September, Esau lost control to the Army Weapons Office, which grew the program during the next eighteen months. Upon determining that nuclear power would not arrive in time to help win the war, the Army relinquished oversight to the Reich Research Council, which Esau headed. He ran the project until falling from political favor.

Unlike the US Manhattan Project, Esau’s nuclear program was geared toward industrial applications of atomic energy, not bomb production. Nuclear science was certainly big business in the Third Reich. Esau oversaw a budget in 1943 worth $1,200,000.7 But this was hundreds of times smaller than the Manhattan Project, whose total cost reached $2 billion. Anxious not to overpromise at a time when Nazi leaders sought “wonder weapons,” Esau deliberately refrained from discussing atomic bombs with his superiors. This was not for lack of military commitment, however, but rather an effort to keep crucial war funds from being wasted on long-term research.

On January 1, 1944, Abraham Esau exchanged his title of “Plenipotentiary for Nuclear Physics” for “Plenipotentiary for High-Frequency Technology.” Infighting within the atomic program had earned Esau the enmity of Albert Speer, the Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production. Nevertheless, as Esau handed the atomic program to his successor, he could boast real victories, including the enrichment of uranium isotopes by means of a centrifuge, application of nuclear physics to biology and medicine, and success with particle accelerators. Esau remained in the good graces of Hermann Göring, head of the Air Force, who gave him control of radio matters.

Esau committed the war crimes for which he was eventually convicted not as a nuclear scientist but through his capacity as Plenipotentiary for High-Frequency Technology. The Third Reich had contracted with an electronics company in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands called Philips to produce hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of materials for the war effort. In the autumn of 1944, as Allied forces advanced, Esau ordered an SS captain named Alfred Boettcher to evacuate equipment from Philips in the Dutch city of Eindhoven to Nazi Germany. Boettcher transported goods valued around $28,000 on three large trucks across the border, engaging in war plunder.

As the Second World War came to an end in 1945, Abraham Esau was apprehended by a special team of American soldiers tasked with finding high-profile Nazi scientists and engineers. Like Albert Speer, the rocketeer Wernher von Braun, and others, Esau was interned and interrogated. In late 1946, Dutch state prosecutors requested that he be transferred to the Netherlands to be tried along with Alfred Boettcher for plundering the Philips electronics company. US officials agreed, deeming Esau less culpable than Speer and less valuable than von Braun. Esau was sent to the Dutch city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, where he remained in prison for eighteen months.8

Esau’s first contact with North American Mennonites came while he was in Dutch prison. After the Second World War, an aid organization called Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) built a robust relief presence in the Netherlands, Germany, and other parts of Europe. This agency had a long history of transnational aid work, dating to the 1920s. It had briefly operated in the Third Reich and Vichy France between 1939 and 1942, until the United States entered the war. For several years, MCC concentrated on North American needs. But with the war’s end, it returned to Europe, where staff distributed food and clothing to those suffering in the wake of violence.9

Mennonite Central Committee recruited some personnel from congregations in Germany and the Netherlands, but its most influential staff were drawn from Canada and the United States. Two early members were Peter and Helene Goertz of Kansas. Peter Goertz was the academic dean of Bethel College, a Mennonite institution of higher education, from which he received leave to work in Europe with his wife during 1947 and 1948. Much of their activity concerned the 45,000 Mennonite refugees from Ukraine, Poland, Germany, and the former Free City of Danzig who were then spread across postwar Europe. Their most unusual case was that of Abraham Esau.

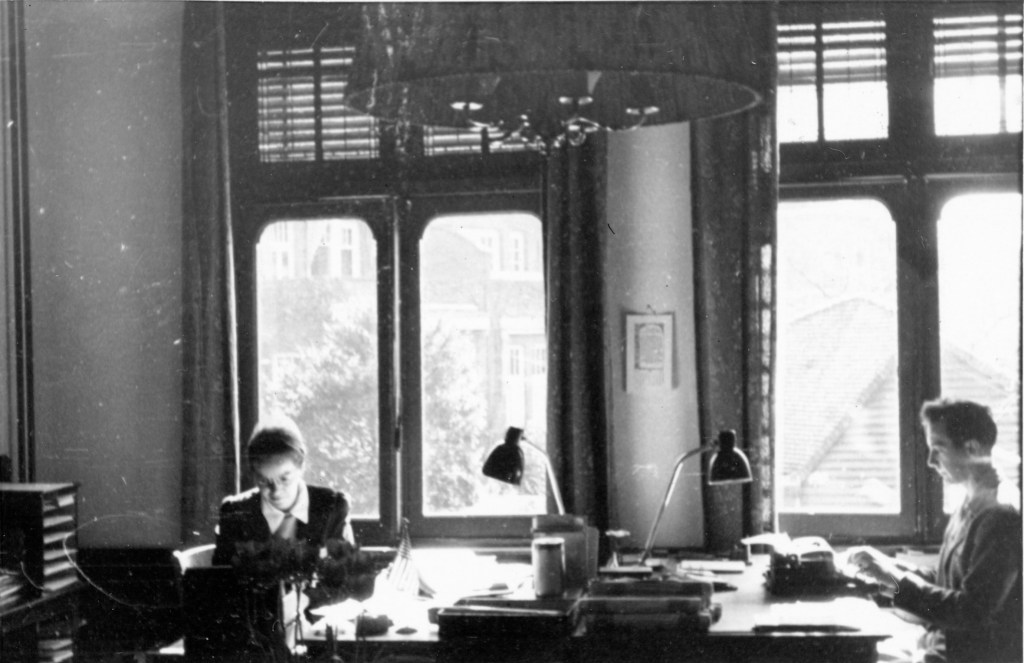

After more than a year of imprisonment in the Netherlands, Esau had become desperate to leave. He wrote letters incessantly, seeking to connect with his former scientific colleagues and to find anyone who could help him achieve freedom. When Esau’s daughter, then living in northern Germany, discovered that a Mennonite Central Committee office had been established in Kiel, she explained her father’s plight and asked if MCC could help. The Kiel office wrote to MCC in Amsterdam, where Peter and Helen Goertz received the request.10 On February 25, 1948, Peter traveled two hours by train to ‘s-Hertogenbosch, where he met with the imprisoned Esau.

Peter Goertz described his encounter with Abraham Esau in correspondence to friends and family in Kansas. Goertz reported that upon arriving at the prison in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, he spent twenty minutes speaking with the warden, who agreed to vacate his office so the two Mennonites could meet in private. They spoke for two hours. To Goertz’s eye, Esau had become a despondent man, in need of “spiritual uplift.” Esau’s demeanor seemed to brighten over the conversation, and he expressed his gratitude so fervently that Goertz himself felt moved. The experience left a deep impression. Back in Amsterdam, he wrote: “Such are rather exciting moments even for me.”11

Over the following months, Peter and Helene Goertz reportedly developed a real friendship with Esau, although from their correspondence, it is hard to escape the thought that the former Nazi scientist cynically played his Mennonite benefactors. Although Peter clearly knew of the charges against Esau, he nonetheless took the prisoner at his word, writing that he “was not a confirmed Nazi,” that he “had been forced to care for physics laboratories in the whole of Germany,” and that “he does not know why he is in prison.”12 Helene, like her husband, expressed awe for Esau’s academic record, describing him as “a great physicist from the German Mennonites.”13

The willingness of Peter and Helene Goertz to believe Esau’s claims of innocence was typical of Mennonite Central Committee’s treatment of other Mennonites from the former Third Reich. After touring several refugee camps, Peter wrote, “It is amazing to me how many of the men from the Danzig area, even among the Mennonites, joined the [Nazi] party.”14 Helene identified attitudes of racism and territorial irredentism among the same group.15 Yet neither they, their colleagues, nor MCC as a whole seem ever to have seriously questioned their project of helping fellow Mennonites. Denominational connections outweighed even known Nazi collaboration.

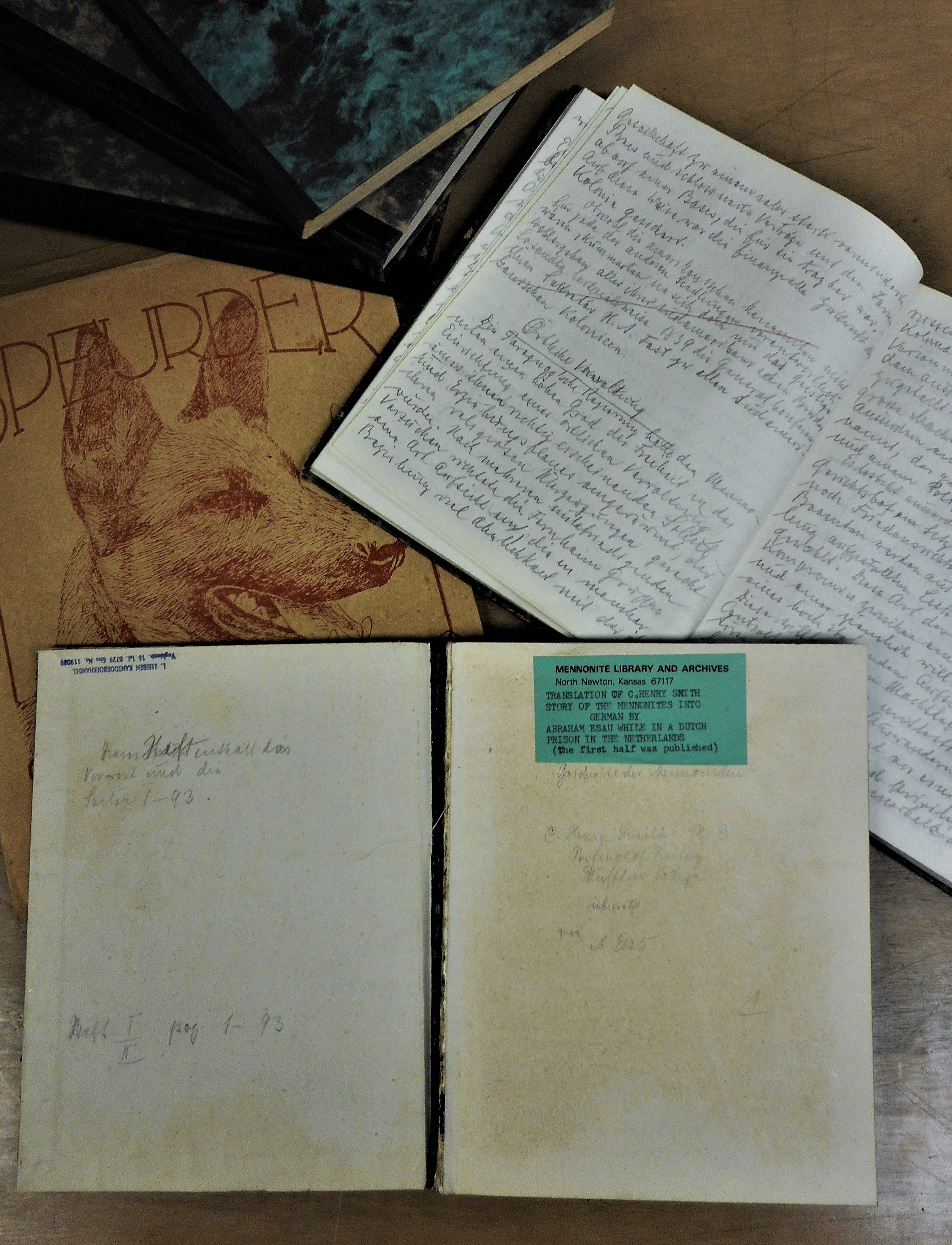

Abraham Esau received several more visits in prison from Peter Goertz, who along with Helene also visited Esau’s daughter in Germany. Peter supplied his imprisoned friend with scientific and religious reading materials. He charged at least one book on electromagnetism to the MCC relief fund.16 Esau was particularly pleased with another volume, The Story of the Mennonites by the US historian C. Henry Smith.17 Commenting that this book should be available to the tens of thousands of Mennonite refugees then scattered across Europe, Esau began translating the 800-page tome into German using pencils and notebooks that Peter Goertz brought from Amsterdam.

On April 27, 1948, a Dutch court in The Hague released Abraham Esau along with his colleague and fellow inmate Alfred Boettcher, the former SS captain, with no criminal conviction. Exactly why Esau and Boettcher were released is unclear. Possibly, one or more of the letters written by Esau and his daughter convinced someone powerful to intercede on the prisoners’ behalf. It is likely that Mennonite Central Committee played at least a minor role, if only by providing Esau with the ability to claim association with a well-known and respected relief agency. MCC at this time held remarkable legal clout with multiple Allied governments, including the Netherlands.

In any event, Esau and Boettcher immediately made their way, after leaving prison, to the MCC center in Amsterdam. Arriving on May 1, they stayed for nearly a month, until May 28, when the two men left for a camp on the Dutch border, eventually arriving back in Germany. While living in the MCC house, Esau and Boettcher became acquainted with many of the leading Mennonite relief workers in Europe, since they regularly passed through Amsterdam. Both visitors penned glowing thank-you notes. Boettcher was touched with the generosity of the MCC workers after his time in isolation, and he was glad to have learned more about Mennonite faith communities.18

Helene Goertz described the weeks Esau and Boettcher spent in Amsterdam in her letters. She referred to both men as “university professors” and considered them to be “proved innocent.” To Helene’s mind, Esau and Boettcher were victims of circumstances, who had nonetheless retained “their manners, their cultured ways, and their sense of humor.”19 The former Nazis washed dishes, carried baggage, and enlivened the atmosphere. Both plied Helene with flowers and fresh fruit. “Prof. Esau has been more than generous since you are away,” Helene wrote to her traveling husband. “Twice while I was sick he sent up some luscious strawberries and once a peach!”20

MCC rendered aid to Abraham Esau on the basis of his Mennonite identity, yet it is unclear that Esau was a practicing Mennonite prior to his contact with Peter and Helene Goertz. He had married a Mennonite (since deceased) and retained other family connections, but I have seen no evidence of any religious contacts between Esau and active Mennonite congregations during the Third Reich. A Mennonite Address Book published in Germany in 1936 does not include Esau’s name, despite printing membership lists for all the congregations to which he would likely have belonged.21 One Nazi-era article referred to him simply as from an “ancient peasant family.”22

Yet Esau represented himself to his MCC friends as a good and faithful fellow Mennonite. He attended church in Amsterdam with Helene Goertz, and he used religious language in his letters to her husband. “I thank God, that He has led me into your house and your family,” Esau wrote to Peter Goertz after leaving Amsterdam. He even portrayed his scientific and administrative activities in the Third Reich as consistent with Christian faith, writing: “I will resume the task which God will give to me with the old energy and in the same manner as before.”23 And all the while, he continued translating The Story of the Mennonites, completing ten pages every day.

Esau had nearly finished his German version of The Story of the Mennonites when he departed the MCC center in May of 1948. He left his completed notebooks with Peter and Helene Goertz. Upon arriving at his daughter’s home in northern Germany, Esau finished the work, and he gave the last part of his translation to MCC workers in Kiel, who then brought this document to the Netherlands. Finally, in mid-1948, Peter and Helene Goertz carried the full manuscript with them back to Kansas, where they deposited it at the Bethel College library. They reported Esau’s own hope that his translation would prove “of some profit for Mennonite circles in the world.”24

At the same time Abraham Esau was reconnecting with his Mennonite heritage, he faced critique from his former scientific colleagues. In the early postwar years, German nuclear physicists formed a remarkably solid front against perceived intrusions by occupying Allied forces. They abandoned old internal disputes and helped one another launch new carriers in the wake of the Third Reich’s collapse. Esau was unusual in being largely dismissed by this group. Physicists like Werner Heisenberg, who had won a Nobel Prize for describing quantum mechanics and had been Esau’s chief rival in the Nazi nuclear program, portrayed Esau as irredeemably tainted.25

Notably, it was the radio scientist Leo Brandt, not a nuclear physicist, who aided Esau’s reentry into Germany’s scientific culture. Brandt knew Esau from earlier radio research and now invited him to North Rhine-Westphalia. In 1949, Esau became a professor in Aachen and joined a new aeronautical research institute. Brandt also nominated Esau for West Germany’s highest federal service prize. But fellow scientists, including the Nobel Prize winner Max von Laue, intervened. Von Laue wrote that during the Nazi period, Esau cast himself as a “chief representative of National Socialism.” A former subordinate also testified that Esau had twice threatened to murder him.26

Upon his death in 1955, Abraham Esau left two remarkably distinct legacies. In the scientific world, he was remembered as an ardent Nazi, rejected after the war by many of his onetime friends. He was also a convicted war criminal, having been re-charged in absentia by a Dutch court and sentenced to time served for plundering the Philips company.27 By contrast, Esau was eulogized by prominent Mennonite intellectuals in Germany and the United States. In 1964, when Esau’s translation of The Story of the Mennonites finally appeared in print, the foreword by Cornelius Krahn of Bethel College praised him as “a man of uncommon creative capacity.”28

The German edition of The Story of the Mennonites sanitized not only Abraham Esau’s past but the broader role of Mennonites in the Third Reich. MCC expressed interest in the manuscript as a means of catering “to our German constituency,” and the US Mennonite General Conference took charge of printing it.29 Cornelius Krahn assembled a team of six readers, including Esau and three other former fascists, who proofed the typed chapters. These appeared in serialized form in a Canadian Mennonite newspaper beginning in 1951. The book’s final version included some additions, but it also entirely omitted a critical original chapter about the Third Reich.

It is appropriate that Abraham Esau, arguably the most powerful Mennonite in the Third Reich, also helped spark—quite unintentionally—the first efforts to publicly reckon with the church’s entanglement with National Socialism. In the same year that Esau’s translation of The Story of the Mennonites appeared, a young Mennonite named Hans-Jürgen Goertz received his doctorate in Germany on the history of radical theology. Goertz, who became a pastor of the Mennonite congregation in Hamburg, took issue with the book’s silence on the Third Reich. He translated the missing chapter and had it serialized in 1965 in a German-language denominational paper.30

Hans-Jürgen Goertz’s resurrection of the redacted chapter on Nazi Germany from The Story of the Mennonites helped ignite a slow-burning interrogation into the denomination’s troubled past. Run-ins with former Nazis as well as Goertz’s own ongoing interest in radical theology led to his landmark 1974 essay, “National Uprising and Religious Downfall,” which alleged that during the Third Reich, Germany’s Mennonites abandoned their principles for nationalism.31 This piece, which sparked still more debate and instigated the first book-length study of the denomination’s Nazi complicity, continues to inspire a process of research and response that is not yet complete.

The story of Hitler’s Mennonite physicist illuminates much of the arc of Mennonite involvement in German nationalism from the late nineteenth century into the postwar era. Abraham Esau’s denominational background primed him to fuse academia with state militarism, allowing him to helm the Nazi nuclear program during the Second World War. Afterwards, the North American Mennonite Central Committee treated Esau, like thousands of other collaborators, as innocent and deserving of aid. Esau, meanwhile, portrayed himself as a model Mennonite, thereby erasing the stain of his war crimes. Being Mennonite suddenly mattered to Esau in an entirely new way.

Mennonites in North America, Europe, and around the globe might reflect on this history of perpetration and denial. Why is it that European Mennonites like Esau found collaboration with Hitler’s genocidal regime so easy and desirable? How could North American Mennonites then so breezily cover for their coreligionists, without raising serious concerns about crimes they might have committed? Abraham Esau’s case may require special soul-searching, given his direct and significant role in the Nazi war machine, as well as his broader impact on the global rise of nuclear weapons. But he was also one among tens of thousands of Mennonite Nazi collaborators.

Ben Goossen is a historian at Harvard University and the author of Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, to be released in paperback from Princeton University Press on May 28.

The author thanks Hans-Jürgen Goertz, Dieter Hoffmann, Bernd-A. Rusinek, Allan Teichroew, John Thiesen, Mark Walker, and Madeline Williams for their help with sources and interpretation.

- The most complete biography of Esau is Dieter Hoffmann and Rüdiger Stutz, “Grenzgänger der Wissenschaft: Abraham Esau als Industriephysiker, Universitätsrektor und Forschungsmanager,” in ‘Kämpferische Wissenschaft’: Studien zur Universität Jena im Nationalsozialismus, ed. Uwe Hoßfeld, Jürgen John, Oliver Lemuth, and Rüdiger Stutz(Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2003), 136-179.↩

- Albert Einstein, Einstein on Peace (New York: Avenel Books, 1968), 295. On the Manhattan Project, see Jeff Hughes, The Manhattan Project: Big Science and the Atom Bomb (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003).↩

- For works that consider Esau’s relationship to Mennonitism, see Horst Penner, “Abraham Esau: Der Große Physiker aus Tiegenhagen,” Mennonitisches Jahrbuch 14 (1974): 54-57; Horst Gerlach, “Abraham Esau: Ein Physiker und Pionier der Nachrichtentechnik,” Westpreußen-Jahrbuch 27 (1977): 57-66; Horst Gerlach, “Esau, Abraham Robert,” MennLex V, online.↩

- Mark Jantzen, Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772-1880 (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010); Benjamin Goossen, Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), 18-95.↩

- See Heidi Tworek, News from Germany: The Competition to Control World Communications, 1900-1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019), 45-69.↩

- Information in this section is from Mark Walker, German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power 1939-1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 17-206; Kristie Mackrakis, Surviving the Swastika: Scientific Research in Nazi Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 162-186.↩

- Klaus Hentschel, ed., Physics and National Socialism (Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1996), 321-322.↩

- Bernd-A. Rusinek, “Deutsche und Niederländische Physiker,” paper given at the conference “Ambivalente Funktionäre: Zur Rolle von Funktionseliten im NS-System,” held November 9-10, 2001 in Osnabrück, Germany, online.↩

- See Benjamin W. Goossen, “Taube und Hakenkreuz: Verhandlungen zwischen der NS-Regierung und dem MCC in Bezug auf die lateinamerikanischen Mennoniten,” Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kultur der Mennoniten in Paraguay 18 (2017): 133-160; Goossen, Chosen Nation, 174-199.↩

- Helene Goertz to C. Henry Smith, September 24, 1948, Cornelius Krahn Collection, Box 5, Folder: Correspondence Horst Quiring 1943-1949, Mennonite Library and Archives, North Newton, Kansas, hereafter MLA.↩

- Peter Goertz to Peter [Unknown], February 26, 1948, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence 1948-1950, MLA.↩

- Peter Goertz to Pat Goertz and Ruth Goertz, February 27, 1948, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence 1948-1950, MLA.↩

- Helene to Family Members, February 27, 1948, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence 1948-1950, MLA.↩

- Peter Goertz to Emil [Unknown] and Rachel [Unknown], November 15, 1947, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence October-December 1947, MLA. On MCC’s postwar refugee efforts, see also Benjamin W. Goossen, “From Aryanism to Anabaptism: Nazi Race Science and the Language of Mennonite Ethnicity,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 90, no. 2 (2016): 135-163.↩

- Helene Goertz to Emil [Unknown] and Rachel [Unknown], November 15, 1947, November 15, 1947, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence October-December 1947, MLA.↩

- Peter Goertz to Dewey Yoder, April 15, 1948, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence 1948-1950, MLA.↩

- C. Henry Smith, The Story of the Mennonites (Berne, IN: Mennonite Book Concern, 1941).↩

- Alfred Boettcher to Helene Goertz, May 30, 1948, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence 1948-1950, MLA.↩

- Helene Goertz to Pat Goertz and Ruth Goertz, May 8, 1948, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence 1948-1950, MLA.↩

- Helene Goertz to Peter Goertz, May 16, 1948, Peter S. Goertz Collection, Box 2, Folder: Correspondence 1948-1950, MLA.↩

- Christian Neff, ed., Mennonitisches Adreßbuch 1936 (Karlsruhe, 1936).↩

- Hentschel, ed., Physics and National Socialism, 324.↩

- Abraham Esau to Peter Goertz, June 17, 1948, Cornelius Krahn Collection, Box 5, Folder: Correspondence Horst Quiring 1943-1949, MLA.↩

- Abraham Esau to Peter Goertz, July 1, 1948, Cornelius Krahn Collection, Box 5, Folder: Correspondence Horst Quiring 1943-1949, MLA.↩

- Klaus Hentschel, The Mental Aftermath: The Mentality of German Physicists 1945-1949 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 96.↩

- Bernd-A. Rusinek, “Leo Brandt: Ein Überblick,” in Leo Brandt (1908-1971): Ingenieur, Wissenschaftsförderer, Visionär, ed. Bernhard Mittermaier and Bernd-A. Rusinek (Jülich: Forschungszentrum Jülich, 2009), 22-23; Bernd-A. Rusinek, “Von der Entdeckung der NS-Vergangenheit zum generellen Faschismusverdacht: Akademische Diskurse in der Bundesrepublik der 60er Jahre,” in Dynamische Zeiten: Die 60er Jahre in den beiden deutschen Gesellschaften, ed. Axel Schildt, Detlef Siegfried, and Karl Christian Lammers (Hamburg: Hans Christians Verlag, 2000), 120.↩

- Bernd-A. Rusinek, “Schwerte/Schneider: Die Karriere eines Spagatakteurs 1936-1995,” in Der Fall Schwerte im Kontext, ed. Helmut König (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1998),44-45.↩

- C. Henry Smith, Die Geschichte der Mennoniten Europas, trans. Abraham Esau (Newton, KS: Faith and Life Press, 1964), Einleitung.↩

- Orie Miller to Cornelius Krahn, October 6, 1948, Cornelius Krahn Collection, Box 5, Folder: Correspondence Horst Quiring 1943-1949, MLA.↩

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz, Umwege zwischen Kanzel und Katheder: Autobiographische Fragmente (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018): 70.↩

- Goertz’s original essay is reprinted with commentary in Marion Kobelt-Groch and Astrid von Schlachta, eds., Mennoniten in der NS-Zeit: Stimmen, Lebenssituationen, Erfahrungen (Bolanden-Weierhof: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 2017), 11-38. For historiographical context, see John Thiesen, “Menno in the KZ or Münster Resurrected: Mennonites and National Socialism,” in European Mennonites and the Challenge of Modernity: Contributors, Detractors, and Adapters, ed. Mark Jantzen, Mary Sprunger, and John Thiesen (North Newton, KS: Bethel College, 2016), 313-328.↩

I notice that one important aspect of this interesting piece appears to be missing. This involves the context in which MCC was working and the changing political atmosphere in postwar Europe. I am speaking of course of the emergence of the Cold War. This saw the rapid polarisation of Europe along new lines, often drawing upon pre-War divisions and anti-communism that hastened the turning of a blind eye (or eyes) to former Nazis. It also saw the rebuilding of western Germany as a bulwark against the Sovietization of Eastern Europe and re-employment of many Germans with dubious links to the former not only in Germany but also in the United States.

LikeLike

Yes, interesting point! Is there any work on the extent to which Mennonites generally and MCC specifically engaged in Cold War/anti-communist ideology, either in North America or in Europe?

LikeLike

Do you know if there’s an English translation of the “National Uprising and Religious Downfall” essay available?

LikeLike

I would also be interested in this! Sounds like a fascinating read.

LikeLike

Unfortunately, Goertz’s 1974 article has never been translated into English, although it has been anthologized several times in German and remains an important document. Goertz’s original essay and its impact within Mennonite communities in West Germany are briefly discussed in the following 1981 article, which I believe also constitutes the first substantive discussion in English of Mennonite-Nazi collaboration: https://ml.bethelks.edu/store/ml/files/1981mar.pdf This article, by Diether Goetz Lichdi, gives a sense of how early debates about Mennonites’ conduct in the Third Reich unfolded in West Germany during the 1970s, and how this issue was still being framed by one of the main participants in the early 1980s. Note that Goertz, Lichdi, and others wrote much more on this topic in subsequent years.

LikeLike

Do you know if there’s an English translation of the “National Uprising and Religious Downfall” essay available?

LikeLike

Good article! Interesting whether or not Peter and/or Helene Goertz, and Abraham Esau were related. My father (born 1914) had 2nd cousins living in East Germany that my parents traveled from Newton KS to visit in 1982, subsequently corresponding in German. John Schmidt (Bethel College) translated the letters. If the “Mennonite game” was played with the Menno German collaborators, would cousin-connections with Mennos in America be found? It’d be an interesting trail to follow…

LikeLike

My point being—could this partially answer how North American Mennonites could cover for their coreligionists, without raising serious concerns about crimes they might have committed? Family connections?

LikeLike

This is a fascinating article, but it seems to be incorrectly attributed to Joel Nofziger rather than Ben Goossen, who is properly credited at the end, as well as on the web page. I’m sure this is just an oversight.

Jeff

LikeLike