Anna Showalter

When people find out that I am planning my wedding for this summer they often ask, “What are Mennonite weddings like?” Sometimes I respond saying, “no dancing, no alcohol,” and enjoy watching the disbelief on my non-Mennonite friends’ faces. In reality, however, there are as many ways to have a Mennonite wedding as there are Mennonites. Despite the inevitable diversity of practice across North American Mennonites, my study of Gospel Herald essays and marriage announcements between 1908-1960 made it clear that Mennonite Church leaders felt strongly that important matters of doctrine and practice were at stake in how church members conducted their marriage ceremonies. Beyond the problem of dress, music and the wedding ring was the question of home wedding versus church wedding. The primary concern was that weddings, whether at home or church, be consistent with Mennonite commitment to simplicity and non-conformity to the world. The shift from home weddings to church weddings meant that weddings were no longer semi-private events but full congregational occasions. Though there is little discussion of what is at stake with this shift in the Gospel Herald it strikes me as a question to pursue. How does the inclusion of marriage vows in congregational worship reflect Mennonite beliefs about marriage in relation to our beliefs about the church as the family of God?

At the turn of the twentieth century, (Old) Mennonites had a firmly established practice of holding wedding ceremonies in the home of either the bride or the officiating bishop. The services were small, involving a handful of close friends and family, often on a Tuesday or Thursday. Gospel Herald marriage announcements usually described these events as a “quiet wedding.” In the late 1920s, however, an occasional “church wedding” appeared in the listing of recent marriages. The trend continued to build slowly so that by 1957 the majority of weddings were held in churches rather than homes.1

Though less is known about Mennonite weddings prior to the twentieth century, we do know that the shift to church weddings did not come without a precedent. The 1890 Minister’s Manual instructs officiants that “The marriage ceremony, according to our present usage, generally takes place at the home of the bride. There is apparently no reason, however, why it should not be performed in the meetinghouse at the time of public services, according to the custom of our brethren in former times, and as is still the custom with some Mennonite churches.”2 An eyewitness account of a nineteenth century Reformed Mennonite wedding describes such a wedding. The couple stood up during Sunday morning worship after a sermon on marriage and divorce, said their marriage vows and then took their (segregated) seats in the congregation.3

Historical precedent or not, the shift back to church weddings in the 1930s and 40s in Mennonite Church communities raised questions and concerns for some. Virginia Conference, for instance, ruled against church weddings entirely in 1900 but modified the prohibition in 1914 to permit weddings to take place at church during regular services.4 The question was still debated in 1944, and Ruben Brubaker wrote to the Gospel Herald to express his concern. “[I] would not encourage the practice of church weddings for [I] feel they will cause drift into worldly practices.”5 A church wedding opened the door for a larger congregation, and increased the visibility of the couple as they made their vows. Even if the wedding was conducted without the pomp and circumstance of attendants, processional, special clothing and flowers, a church wedding would still be a larger, public event in contrast to the “quiet wedding” of previous years.

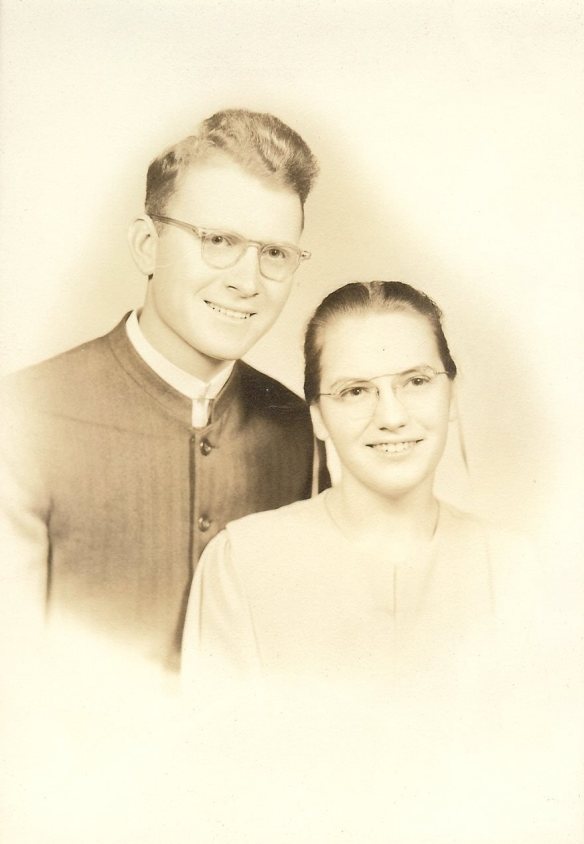

John and Doris Sollenberger married December 9, 1951 during Sunday morning worship at the Rowe Mennonite Church. The bride wore blue.

My own grandparents exchanged their marriage vows during Sunday morning worship at the Rowe Mennonite Church near Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, in 1951. They wore their Sunday best and stood up during church at the appointed time to say their vows. My grandma remembers her mother-in-law cautioning her against this plan in favor of a low-profile home wedding that would not draw unnecessary attention to the couple. My grandparents, however, felt that since Grandpa had recently been ordained as a minister, it was fitting for them to take their marriage vows in the midst of their church community.

Despite a cautious attitude toward church weddings in general, several essays in the Gospel Herald show that my grandparents were not alone in believing that the church body gathered at the meetinghouse was potentially an ideal context to make marriage vows. One voice representative of this view was Amos Weaver of Ronks, Pennsylvania. In 1956, he noted the shift to church weddings as a positive change:

Until about 10 years ago Mennonite church weddings were practically unknown in many communities. Today, any other type of wedding is a rare thing. To have this very important God-given ordinance of holy matrimony solemnized publicly in the church of Christ certainly seems right and proper for a Christian. Many of us will say it is a change for the better.

Amos Weaver went on to clarify that this change could only be positive if done with the utmost simplicity within the context of regular church worship. Any added frills would obscure the advantage of explicitly placing marriage vows in the midst of corporate worship. Weaver described the church wedding he would advocate:

We could have a church wedding with all of the advantages of the church’s sanction and blessing by including it in a regular church service without all the fanfare we now have. I believe all the truly spiritual values to be had in a church wedding for the bridal couple and for the brotherhood would be retained and enhanced by a simple marriage ceremony in connection with a regular Sunday morning or Sunday evening service. No dramatic arrangements staged for the bridal party to enter at timed intervals, and no tableau of specially gowned attendants would be necessary.6

It appears that for Weaver and his like-minded contemporaries, the primary issue at stake was simplicity, economy and non-conformity to worldly wedding practices. I wonder, however, if in addition to the exhortation to simplicity, a subtext running underneath conversations about changing wedding practices is the question of how marriage vows belong in the life and worship of the church. Perhaps unarticulated in the hesitation to shift weddings from semi-private events to full congregational occasions is concern about a fine line between elevating the romantic couple in the public eye and maintaining the simplicity of a community of Christian brothers and sisters.

My study of Mennonite home and church weddings leaves me with more questions than answers. For instance, is it possible to read the inclusion of marriage vows in congregational worship as potentially, very subtly, obscuring the Christian claim that it is our baptismal vows rather than our family ties that constitute our membership in the family of God? Alternatively, could such an inclusion be read as acknowledging the particularity of the marriage vow while placing it in the context of community instead of romanticizing the idea of an insular, self-containing couple? In a cultural moment in which marriage practices are changing, today Mennonites have the opportunity to again consider how to make marriage vows in a way that communications our convictions about human marriage and the family of God.

- Orville R. Stutzman, “Vital Statistics,” Gospel Herald 50 (Nov 12, 1957): 970. ↩

- Confession of Faith and Minister’s Manual (Elkhart In: Mennonite Publishing Company, 1890). 89. ↩

- Phebe Earle Gibbons, Pennsylvania Dutch and Other Essays (Philadelphia Pa: J.B. Lippincott & Co, 1872), 28-31. ↩

- Minutes of the Virginia Mennonite Conference (1835-1938), (Scottdale Pa: Virginia Mennonite Conference, 1939), 56, 109. ↩

- Ruben Brubaker, “Church Weddings,” Gospel Herald 37 (October 13, 1944): 557. ↩

- Amos W. Weaver, “Weddings,” Gospel Herald 49 (June 26, 1956): 622. ↩

Anna, in my genealogy research, I have found that both my paternal grandparents and paternal great grandparents were married by nonMennonite ministers, neither in the bride’s home or in the church. This surprised me but I have found their marriage records and the names of the ministers who performed their ceremonies. In the case of my great grands, it would have been prior to 1900s but my grandparents were married in 1913. I am thinking that perhaps something prevented Mennonite ministers from having legal authority and hence the couples needed to get married by nonMennonite ministers. I need to do more checking. I assume you have not encountered this in your research. Both families were firmly rooted at Franconia Mennonite Church, a large historic church in the area.

LikeLike

My own parents, J. Landis Weaver and Ada S. Horst, were married at the home of the bishop in charge of the Ephrata congregation in 1931. My dad told me about the first couple to be married in the meeting house at Ephrata congregation of the Lancaster Conference. They were given permission by the bishop, but it was required that the shutters be closed so that the neighbors did not know what was happening there.

In 1954, I was a member of a male quartet that was to sing at a wedding to take place in a Lancaster Conference church. When we were introduced by the minister, the congregation was advised that if they knew the music, they could sing along. Of course, nobody did, for they all understood that this invitation was simply a way to avoid the use of so-called special music in the church building.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for publishing this article! Any chance I could get access to all of Amos Weaver’s article?

LikeLike

Send me an email through the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society and I will see what I can do to help that to you.

LikeLike