By Ben Goossen

What does it mean to bring the “Anabaptist past into a digital century”? The subtitle of this blog includes a playful reference to the anti-modernist stance of many Amish, Mennonites, Hutterites, and other so-called Plain Peoples—as well as an acknowledgement of the widely-held stereotype that Anabaptists do not use technology or engage the modern world. On one hand, the mission of Anabaptist Historians parallels that of any historical organization, namely to uncover, interpret, and make accessible the records of bygone eras for twenty-first century audiences. Yet for scholars of Anabaptism, this task holds unique challenges as well as opportunities.

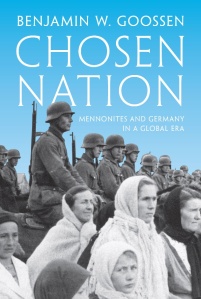

Documents in the German Mennonite Sources Database were collected during the research for Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era (Princeton University Press, 2017)

“Digital History” is a practice that, over the past several years, has increasingly shaped the historical profession. In a narrow sense, Digital History refers to projects that primarily use digital tools to tell historical stories, such as animated maps, YouTube documentaries, or interactive wikis. Anabaptist-related efforts such as the extensive Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO) or the Bearing Witness website, designed to collect stories of persecuted Anabaptists from around the world, fit this definition. At an even broader level, nearly all history done today is “digital” in some way. It is hard to imagine writing an article or reviewing a book without opening Google, consulting an online repository like JSTOR, or downloading an open-access journal. Sending emails, maintaining websites, and using search engines are all part of Digital History.

Some Anabaptist groups are today among the only populations that write history without digital tools. In the summer of 2016, when the Anabaptist Historians Editorial Board was starting this blog, one tough question was how to include conservative Amish and other historians who do not use the internet. Is it possible to represent the full spectrum of Anabaptist pasts and identities in a digital format? Or does the very nature of a blog preclude the participation and accurate representation of some groups? We tried to create a website defined by simplicity – a value with cachet in Anabaptist households and Silicon Valley alike – yet reaching conservative populations remains difficult. When communicating with one historian in the Weaverland Conference, for example, I copy and paste web text into my messages or send screenshots as attachments, since he uses email but no internet browsers.

In other circumstances, Anabaptist history can feel tailor-made for digital approaches. With a relatively small population – around two million members are active worldwide – major digital projects are more feasible than they would be for larger demographics. Anabaptism, as a religious movement, is also blessed with substantial institutional resources, including church libraries, denominational archives, and nongovernmental organizations. Many have already undertaken Digital History initiatives. And joining these is a vast webscape of informal Twitter feeds, Facebook pages, chat room support groups, and genealogical sites. Previous posts on this blog have begun a fascinating dialogue about the places where Anabaptist history happens, including discussions of the value of borderland perspectives, centralized archives, and public history. How can we think about cyberspace as a location of and platform for historical work?

Over the past seven years, I have been working on a large-scale digitization project, the German Mennonite Sources Database. Released in October and hosted online by the Mennonite Library and Archives in North Newton, Kansas, this is the largest digital repository of books and newspapers by or about Mennonites in Germany as well as one of the most complete collections on this subject anywhere in the world. The database spans the years 1800 to 1950 and includes approximately 100,000 pages of text, including thousands of books, pamphlets, newsletters, and articles. Its purpose is to make historical resources available to anyone who reads German and is interested in religious history. Readers will find documents pertaining to virtually every aspect of German Mennonite life, ranging from sermons and catechisms to texts on nonresistance, the draft, and Nazism. Some topics are expected, such as hymn selections and condemnations of oath swearing. Others less so – like an 1859 rumination on vampires in the world’s first journal of folklore.

The German Mennonite Sources Database began as a personal resource, growing out of research conducted for my book, Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era, forthcoming in 2017 from Princeton University Press. As a history of Mennonites’ worldwide entanglement with German nationalism during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Chosen Nation required familiarity with a wide spectrum of issues, from congregational and institutional life to historical, educational, and mission activities, involvement in war and political movements, peace declarations, gender, genocide, and anti-Semitism. In archives across Europe and the Americas, I found myself digitizing dozens or sometimes hundreds of documents a day. The essential tools of the Digital Historian include a computer, cell phone, digital camera, and a bevy of cords, adapters, and USB sticks. My archival desks unfailingly resembled a crow’s nest of snaking wires and metallic boxes.

A major advantage of Digital History is its ability to make scarce resources widely available. Documents that might exist only in one or two places in the world become accessible to anyone with a modem. This has a democratizing effect, since travel to distant libraries or archives usually requires deep pockets or university support, while digital files can be downloaded from the comfort of home. With Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software and online translation services (some of which now use artificial intelligence), texts in German or other languages can be rendered quickly and with stunning accuracy into English. Still another advantage is that different researchers bring diverse perspectives to the same sources. Documents in the German Mennonite Sources Database, for instance, might find wide interest beyond my initial purposes – hopefully providing a basis for articles, dissertations, scholarly debates, and family research.

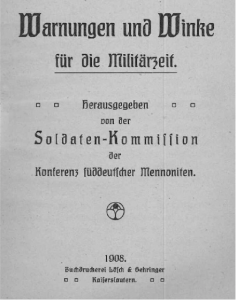

Warnings and Suggestions for Military Service, a handbook for Mennonite soldiers, is one of thousands of books, pamphlets, and articles now available via the German Mennonite Sources Database

Not all history is digital, of course, and not all Digital History is good. While open-access sites like the German Mennonite Sources Database are available to all, many research venues like Ancestry.com or HeinOnline lock material that would be provided for free in physical libraries behind digital paywalls. In this age of uneven globalization, the web remains only partially worldwide, with internet unavailable to the earth’s most disadvantaged populations – those lacking power in both senses of the word. As Anabaptists, we are also attuned to the spiritual politics of the internet. Is it possible to use digital tools in ways that are constructive rather than damaging, uniting rather than alienating? Such questions resonate with current public debates about internet bullying, cyberterrorism, and fake news. Some plain Anabaptists find a solution in eschewing digital resources altogether.

Our challenge then, as Anabaptist historians, is to consider not only how to engage Digital History, but also how to do so responsibly. Can we find ways of digitizing library holdings that also increase donations and visits to physical locations? Can we build integrated networks to share data and exchange ideas without losing sight of the distinctive needs and identities within the Anabaptist church family? Perhaps we could take cues from the wonderful work already undertaken by friends and colleagues – such as the open access website of Anabaptist Witness, the database of Anabaptist-related websites hosted by Mennonite Church USA, or the breathtaking Mennonite Archival Image Database. The tools offered by Digital History are like any new resource. They invite us to explore and affirm their limitations, while also finding fresh ways of working together.

You can access the German Mennonite Sources Database here.

Thanks to John Thiesen and the Mennonite Library and Archives for hosting the German Mennonite Sources Database, as well as to Rosalind Andreas, Kevin Enns-Rempel, Rachel Waltner Goossen, Royden Loewen, Titus Peachey, John Roth, Astrid von Schlachta, and Paul Toews for their support.

Material on Russian Mennonites has been posted for many years on William Vogt’s Chortitza website and is regularly added to.

LikeLike

Thanks, James – yes wonderful historical materials on Russian Mennonites here: http://chort.square7.ch/ And on US Mennonites here: https://archive.org/details/mennonitehistoricallibrarygoshen It would be terrific if these and other resources could be integrated into a unified platform for easy access, searching, and cross-referencing

LikeLike

Thank you for a great post, you helped me a lot.

LikeLike