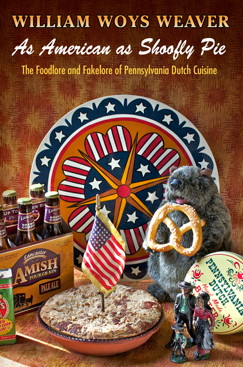

As American as Shoofly Pie: The Foodlore and Fakelore of Pennsylvania Dutch Cuisine1 by William Woys Weaver is many things: it is a detailed look at the foodways among the Pennsylvania Dutch, a commentary on modern culture, and a cookbook. It is scholarly and snarky. It purposely does not focus on Anabaptists, though it does deal extensively with the Amish in popular imagination. Weaver states in his introduction: “In terms of the larger culinary story, the Amish are mostly marginal anyway because the real centers of creative Pennsylvania Dutch cookery were in the towns and not to be found among the outlying Amish or Mennonite communities, even though today the Mennonites have attempted to preempt the Amish as their cultural public-relations handlers in their Amish and Mennonite cookbooks to press for ‘Christian’ culinary values—whatever that may mean” (7). He is also clear that one of his major criteria for the recipes he highlights in the book was to contrast against the “artificial portrait” created by Amish tourism (8).

What Weaver sets about doing in As American as Shoofly Pie is to take food as the avenue into Pennsylvania Dutch culture to discuss its identity markers—historic and current—as well as the class dynamics involved, portrayals in popular culture, and the commercially driven conflation of the Amish and Pennsylvania Dutch. He details cooking implements, the “cabbage wall” of sauerkraut defining the borders of Pennsylvania Dutch country, how the Amish imagery became normative for Pennsylvania Dutch tourism, and how the culture is renewing itself. It is an excellent read, both informative and engagingly written.2

I use here the term “Pennsylvania Dutch” instead of “Pennsylvania German” for two reasons: first, because that is the terminology of Weaver, and second, because the “Pennsylvania Dutch” have no connection to the nation-state of Germany, past or present. On the second point, I will offer a story from my wife’s family history:

When Pop-Pop Riegle was a prisoner of war in Germany during World War II, the camp taught German to the POWs. The guards doubled over in laughter to hear the POWs from New York City try to pronounce words with a New York accent. My grandfather, from what I understand, could converse with the guards easily, because he spoke Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch. The German guards asked him why he was fighting for the wrong side. To them, speaking German meant loyalty to Deutschland. For my grandfather, speaking a German dialect was part of his American culture.

Furthermore, it seems this story is borne out in every ethnography of the Pennsylvania Dutch I have encountered. They all carry a variation of the following: A researcher walks up to some Pennsylvania Dutch women and asks them about how they describe themselves, only to be rebuffed with, “We’re not Pennsylvania Dutch, we’re American.” The Pennsylvania Dutch are an American cultural group consisting of a blend of German speakers, mostly Palatinate and Swiss, who settled together. The eponym “Dutch” has long roots going back into medieval Europe as a term for western German speakers. They can be divided into two broad categories, the Plain Dutch, such as the Amish and Mennonites, or the Gay (Fancy) Dutch, such as my wife’s Lutheran and Reformed forebears.

It is important for Mennonite scholars to remember that Mennonite fish were just one school swimming in Pennsylvania Dutch water. Even though they may have been marginal in shaping Pennsylvania Dutch culture, as Weaver notes, they were still shaped by it. Mennonites all across South Central Pennsylvania were surrounded by people who spoke, ate, and worked in the same ways they did—the majority of them Lutheran or Reformed, but also the Amish, Church of the Brethren, and other plain Anabaptists.[^3] As Felipe Hinojosa has noted, place matters—both in space and time, as well as culturally. The Swiss-German strain of the Mennonite experience practiced their faith and promulgated their beliefs not in ethnic colonies but surrounded by a shared culture that itself was distinctive from broader America. Surely this has led to a different way of knowing and living as Mennonites. For this reason, scholars dealing with Mennonite identity must familiarize themselves with Pennsylvania Dutch culture. For its insistence on placing the Pennsylvania Dutch culture within the broader national culture, and his disgust at the conflation of the Amish with the Pennsylvania Dutch, Weaver’s As American as Shoofly Pie is an excellent place to start.

- William Woys Weaver, As American as Shoofly Pie: The Foodlore and Fakelore of Pennsylvania Dutch Cuisine (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). ↩

-

This is not to say there are no points where I disagree with Weaver. For example, his repetition of Rufus Jones’ claim that the Amish adapted bonnets from Quakers as “common knowledge” (135) is uncritical at best.

[^3] Moravians are one of the German groups that maintained a markedly different culture than that of the Pennsylvania Dutch. ↩

Thanks for the thoughtful essay. There’s a lot to chew over in the last paragraph. It’s also worth noting that many members of the “Swiss-German strain of the Mennonite experience” never lived in Lancaster County, or at least haven’t been in its orbit for over two centuries. In other words, Mennonites and Amish would have actually been the only Pennsylvania Dutch speakers in Indiana, Ohio or Iowa without the broader cultural context of Dutchness you rightfully describe here. (In Kitchener/Waterloo, on the other hand, the Pennsylvania Dutch were part of a larger community with a strong German identity.) In all of these communities, I’m guessing that the maintenance of Pennsylvania Dutch language and culture meant something different.

LikeLike